Researchers at CMU’s Morphing Matter Lab have developed a technique for 4D printing that could prove popular.

4D printing, if you are not familiar, is a variation of 3D printing in which the printed object is not static but somehow changes shape after normal 3D printing completes. There are a number of research projects underway in this area exploring ideas such as automatic unfolding of objects larger than the build volume, or mechanical muscles or even switches.

The CMU MML project developed a rather simple technique for creating such shapes, in particular when the trigger for folding is heat.

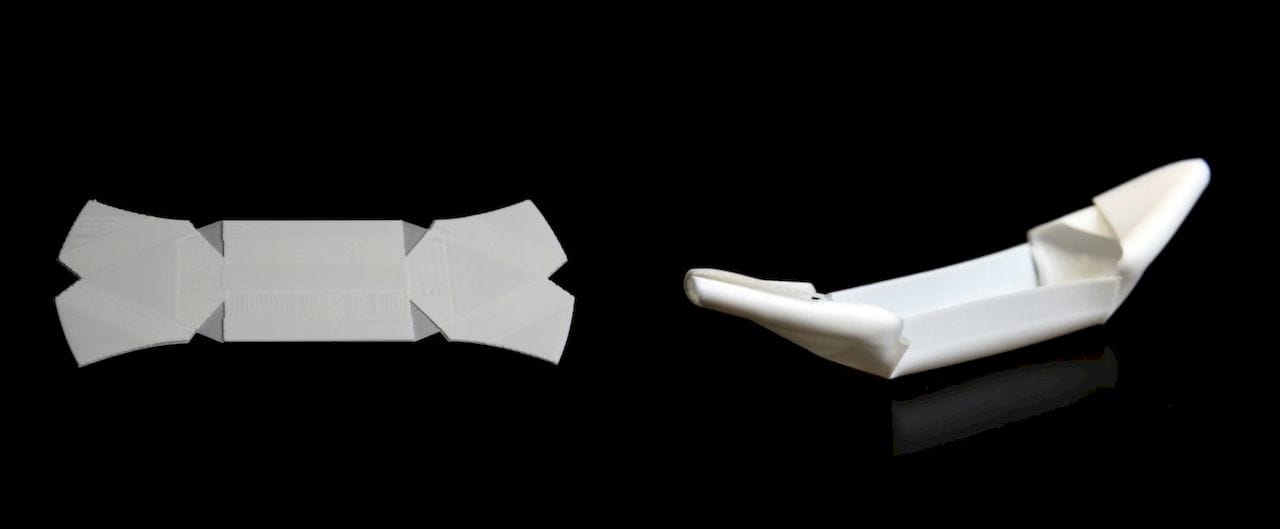

They devised several simple shapes and printed a flat, unfolded representation of the object. However, the nature of the few deposition layers was carefully computed to induce variable zones of warping. These controlled warps caused the prints to “morph” into the target 3D shape.

In a way, it’s like printing in 2D and then changing the result into 3D, as opposed to printing in 3D and then moving into the fourth dimension.

The researchers were able to produce several interesting and actually functional objects using this process, which involves adjusting the GCODE in interesting ways. They explain:

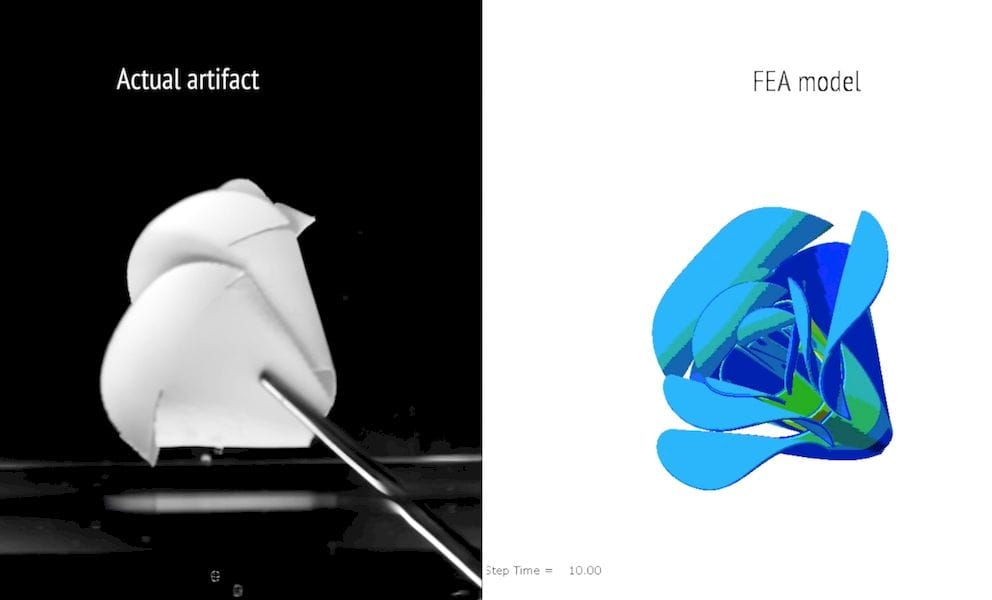

Though we used a 3D printer with standard hardware, we replaced the machine’s open source software with their own code that automatically calculates the print speed and patterns necessary to achieve particular folding angles. The software is based on new curve-folding theory representing banding motions of curved area. The software based on this theory can compile any arbitrary 3-D mesh shape to an associated thermoplastic sheet in a few seconds without human intervention.

Evidently their process involves some form of dynamic finite element analysis, where competing forces within the part cause the deformation.

Their video is fascinating to watch, particularly with the WestWorld-like background music:

They describe the process as “self-folding”, but actually in real life this could become a “self-assembling” process. One wonders whether this approach can be scaled up to enable the self-assembly of larger objects, like furniture.

I don’t know if it would be possible to open up the IKEA box and blast it with a heat gun to unfold your new table, but that would be quite desirable.

There are many potential applications for this technology, ranging from more compact spacecraft launches to animated fashion elements that react to the weather.

I’m hoping they publicly release some of their model generation code so that others can explore the possibilities and develop unique applications.

Perhaps the next letter you get in the mail will contain something quite different.

The Birthday Card industry will never be the same.