![A 4D 3D printed object using a gray-scale printing technique [Source: IopScience]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a5c79ef68.jpg)

Researchers have developed a very interesting method of actuating 3D prints.

“4D” printing is a variant of 3D printing in which the printed object moves or otherwise changes shape after printing. A simple example would be a way to have a print “unfold” after being 3D printed in a build chamber that’s smaller than the intended final size of the object.

4D can be “one way” in the sense that the unfolding happens and cannot be reversed. But it is also possible to print a 4D object that has the ability to be restored to its original shape.

But how do you produce such an object?

Researchers were able to devise a system to do exactly this. They explain:

“Structures and devices with reversible shape change (RSC) are highly desirable in many applications such as mechanical actuators, soft robotics, and artificial muscles.

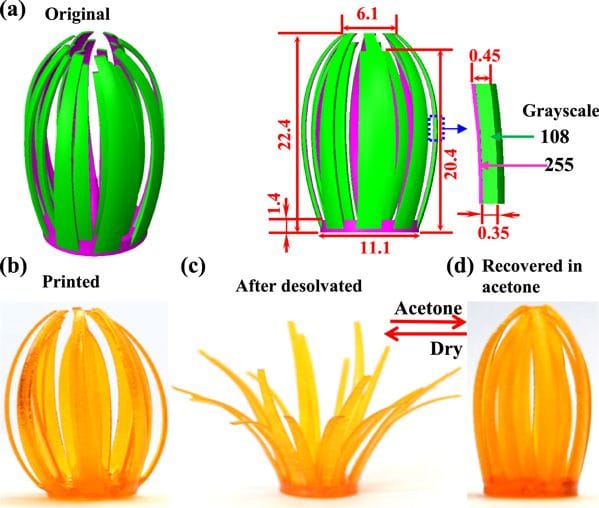

In this paper, we propose to use 3D grayscale printing method to create reversible self-folding structures. The grayscale pattern was used to control the light intensity distribution of a UV projector in a digital light processing 3D printer such that the same photo irradiation time leads to different curing degrees and thus different crosslinking densities at different locations in the polymer during 3D printing.

After leaching the uncured oligomers inside the loosely crosslinked network, bending deformation could be induced due to the volume shrinkage. The bending deformation was reversed if the bent structure absorbed acetone and swelled.

Using this method, we designed and created RSC structures such as reversible pattern transformation and self-expanding/shrinking structures, auxetic metamaterial, structures mimicking the blossom of a flower.”

![A 4D 3D printed object using a gray-scale printing technique [Source: IopScience]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a5c80d577.jpg)

It seems they produced a photopolymer resin containing reversibly activated materials, and then varied the density of the material throughout an object. The 3D printer simply fuses “more” polymer in designated areas as it prints.

Imagine the cross-section of an object, where there might be a “density gradient”. When activated, the object bends in a complex manner as the gradient makes it respond differently in different areas.

There are likely many possible mechanical designs for simple motion mechanisms using this approach. I can even imagine a library of commonly used components that could be incorporated into a design, making it possible to 3D print many possible “solid” 3D printable mechanisms.

![A 4D 3D printed pattern using a gray-scale printing technique [Source: IopScience]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a5c85e9b9.jpg)

One challenge with this approach is that the method of activation is fixed, based on the mixture of liquid photopolymer. If, for example, the activation trigger is light, then your 3D printed 4D object will only activate with light – and all portions exposed to light might activate simultaneously. If you wanted to mix different triggers, such as electricity, magnetic field, or heat, that might require a much more complicated liquid polymer that mixed different trigger molecules.

Via IopScience

A research thesis details the incredibly complex world of volumetric 3D printing. We review the highlights.