Carbon announced a new production application that has a stunning application: programmable protective cases.

The resin-3D printer manufacturer has been seeking production applications for their increasingly popular Digital Light Synthesis™ (DLS) technology. This fascinating technology permits their 3D printer to operate faster than most typical resin 3D printers because it features an oxygen-powered layer to avoid the lengthy “peel” process other machines must use to rip freshly 3D printed layers off the bottom of the resin tank.

Carbon has had their chemists at work developing a wide variety of liquid resin materials designed specifically for production use. That is, the parts 3D printed on the Carbon systems are not necessarily for mere prototyping, but can be used in actual, real-life situations where all engineering parameters are in force.

This is Carbon’s strategy: develop a system (including machine, materials and services) that are suitable for production use. I suspect it’s also because that is where they can find an enormous amount of revenue.

But there’s one catch: They need to convince manufacturers to adopt their technology, and that’s a difficult thing to do.

Manufacturers have often been in business for decades, developing entrenched methods of production based on traditional technologies. Readers of this blog may scoff at this notion, but it’s very true. Most people just don’t want to change things, and takes considerable effort to persuade them to do so. This is particularly true when the result of the change is not that different from where you started.

Thus Carbon’s strategy is to enable manufacturers to produce items they absolutely could not produce with existing tools. This means entirely new designs using undreamed of features.

And so far Carbon seems to have been successful. They’ve persuaded at least one notable footwear company (Adidas) to take part, producing an unusual 3D printed midsoles.

Today they announce another similar partnership, this time with InCase, the manufacturers of a wide variety of technology accessory products, including smartphone cases.

But wait, you say, there’s nothing special about cases, they’re just a hunk of solid plastic.

That’s what they were before, but they won’t be for longer, at least if Carbon’s strategy plays out successfully.

The idea is that the 3D design for a smartphone case can be programmatically generated and take into account the stresses required to effect the protective features of the case.

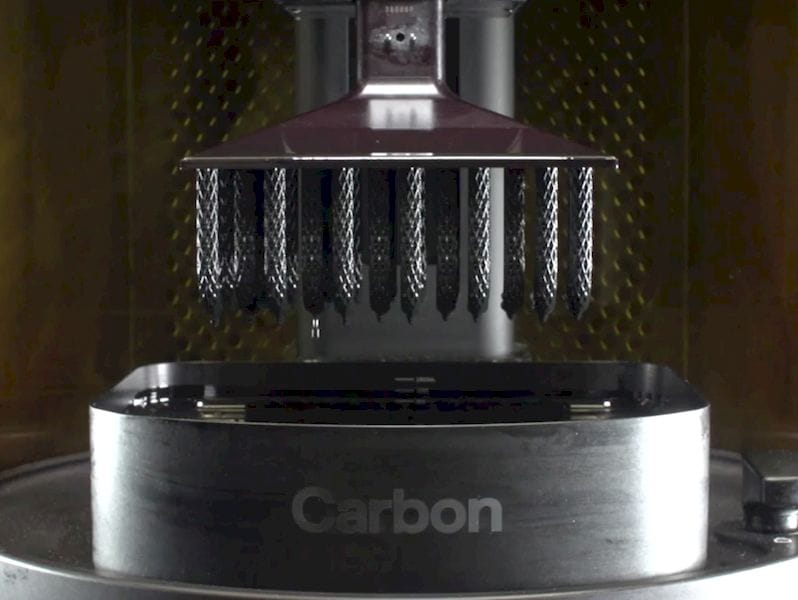

For example, imagine a corner of the case being made from a lattice-like structure underneath the otherwise unremarkable smooth surface. This sparse structure could be able to absorb more force than a solid structure, if designed properly.

Imagine further that an analysis shows where the points of likely maximum impact might occur on a specific type of case. These areas could be designed to have a more appropriate lattice, which might seamlessly merge into a different zone.

I think you get the idea here. These cases would use potentially less material and thus be lighter, yet provide more protection.

And there’s also the possibility of highly unusual aesthetic effects if you have full digital control over the 3D shape.

Wait, there’s more. I’m talking about smartphone cases. You can extend this concept to tablets also, without too much surprise. But InCase makes much more than just smartphone cases. They produce backpacks, shoulder bags, accessories, sleeves, laptop bags, chargers, travel bags and lots of other things.

Any of these could use this functionality.

In ways we cannot yet imagine.

Via Carbon