Researchers are refining a very simple process for smoothing 3D prints.

Those first seeing 3D prints from a filament-based 3D printer often comment about the layer lines caused by the often coarse layers that are clearly visible and most certainly sensed by touch. It’s an unfamiliar sensation as most common items are mass manufactured in processes that result in perfectly smooth surfaces.

Smoothing such prints has always been a challenge. At first people would simply sand them by hand. This usually took multiple passes with increasingly finer grit and primer paint to obtain excellent quality surfaces. However, that’s a huge amount of manual labor and it doesn’t work at all for some complex geometries where it’s nearly impossible to get sandpaper near the surface.

Another technique often used is tumbling, where a fresh print is tossed into an agitated tank filled with appropriate tumbling media. This works reasonably well for simple surfaces, but don’t keep your hopes up if you have any delicate structures in your object as they could get broken off.

Another technique is to use chemical means. Some materials soften when exposed to certain vapors. The most frequently used combination is acetone vapor for ABS plastic prints. This works well if timed properly, but the acetone is a nasty substance that presents a significant fire hazard and cannot be used in all situations. Also small details tend to “disappear” using this process, which by definition is applied equally to all surfaces regardless of need. There are other formulations, but they tend to be expensive, toxic or work only on certain materials.

The new research, done by Kensuke Takagishi and Shinjiro Umezu, is at first similar to the acetone approach where instead of using vapor, acetone is painted onto the surface of the model. Usually this is not done as the process of doing so is highly inaccurate and can make the model worse.

The key of this research is how to do this in an optimal manner, which they call “3D-CMF”, which stands for 3D chemical melting finishing. They explain:

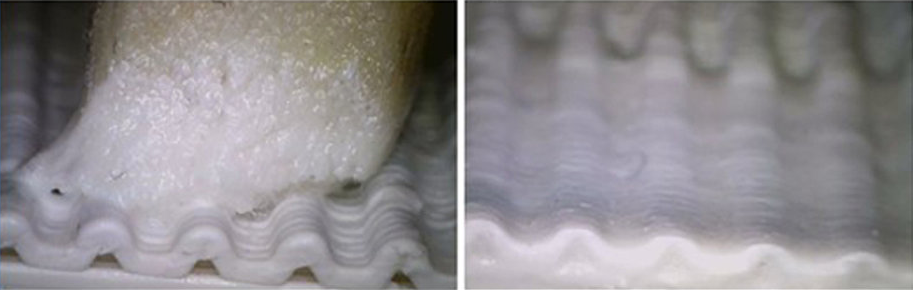

In this method, a pen-style device is filled with a chemical able to dissolve the materials used for building 3D printed structures. By controlling the behavior of this pen-style device, the convex parts of layer grooves on the surface of the 3D printed structure are dissolved, which, in turn, fills the concave parts.

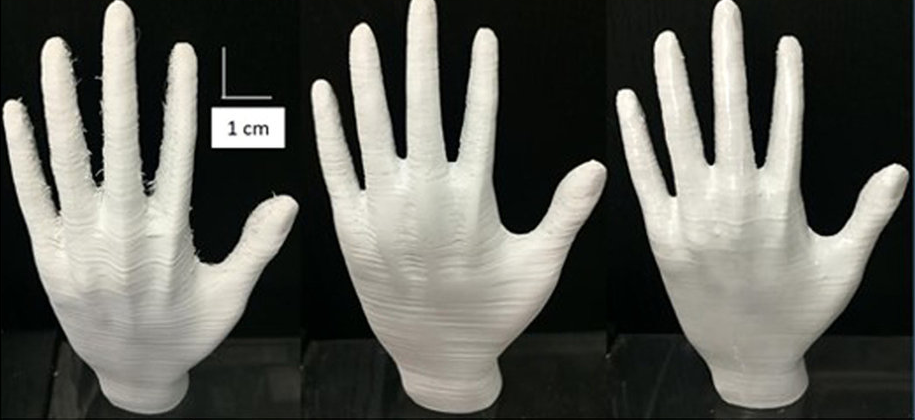

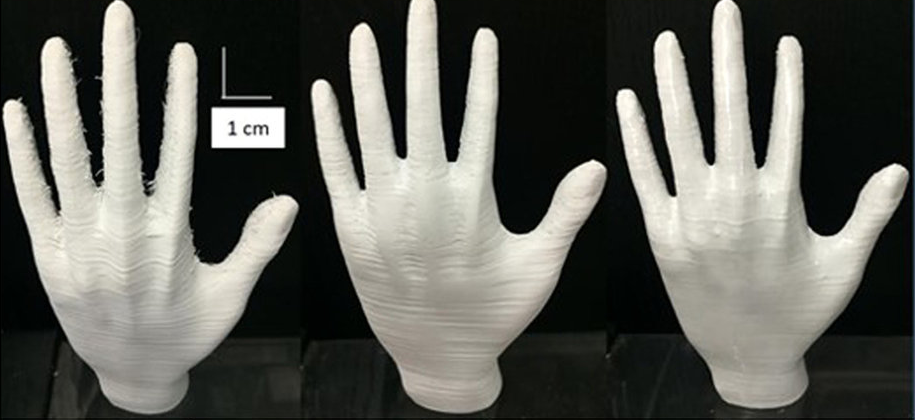

These image shows part of their process. They change the pen tips to ensure the tip size and shape corresponds to the layersize. They also precisely control the force applied to the pen, resulting in a very good surface.

Their research attempted a variety of scenarios and in each they measured the results to prove which approach was optimal. This is so vastly different than “just doing it by hand”.

They also found that repeated treatments could almost completely eliminate the layers and specifically found how many attempts would be required for arbitrary layer configurations.

Of course, there are no products on the market for this technology as yet, but it seems sufficiently useful to warrant at least investigating doing so. However, it may be that there isn’t a lot of money potential as the equipment may be inexpensive and there are not that many 3D printer operators that would demand such a product.

Via Nature