I’m looking today at a new 3D printing company that focuses on building construction, Cazza.

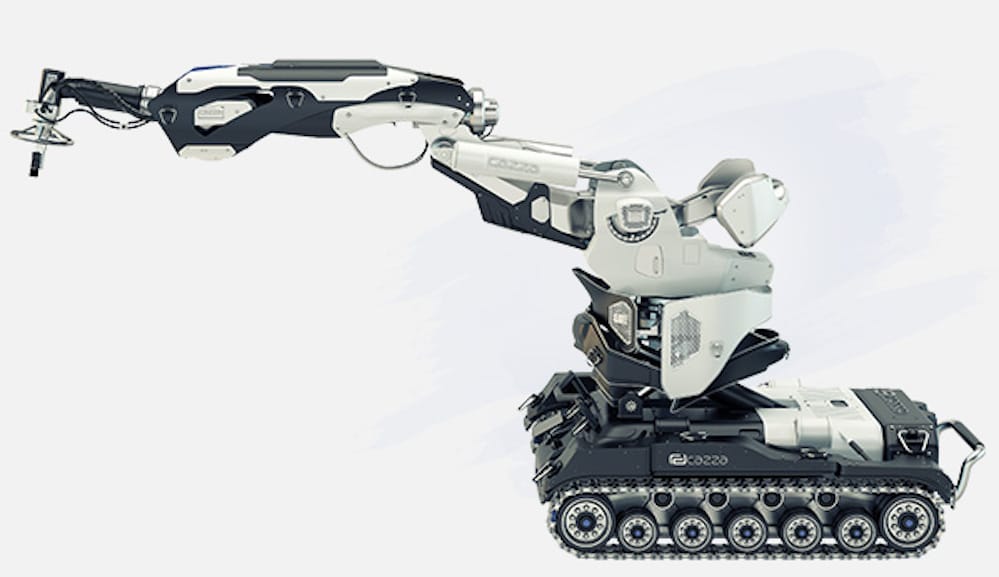

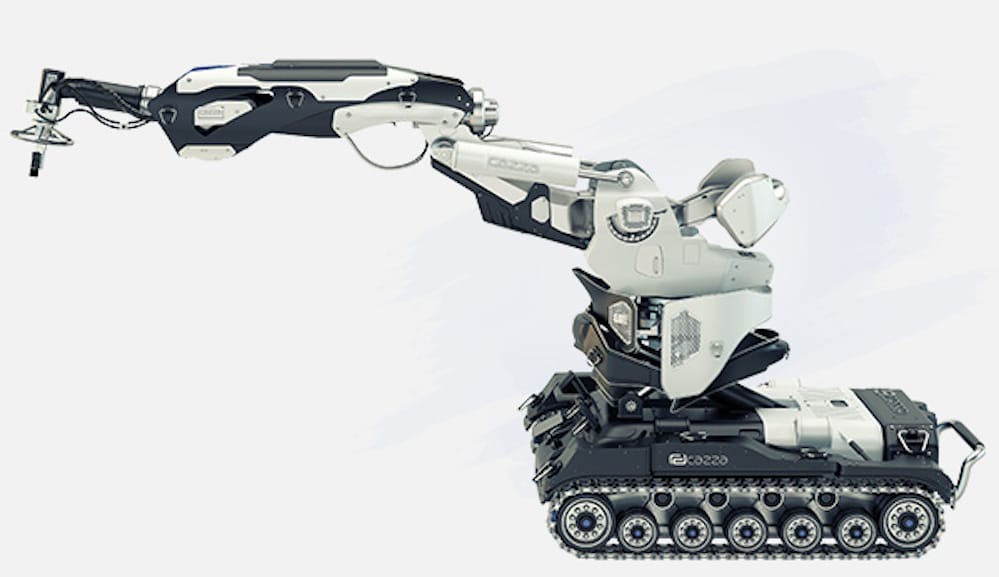

The Finland-based company produces a pair of mobile 3D printers specialized for building construction, using a robotic approach. These two units, the Cazza X1 and Cazza X1 Core accept a supply of pumped concrete and extrude it in layers to form the concrete portions of small buildings.

As you can see in the image at top, the machines are mobile, but do have a limited reach. However, that reach is sufficient to enable the robots to extrude building-sized objects, well, buildings, up to a couple of floors high.

We’ve seen concrete extrusion before, but there seems to be a difference in Cazza’s approach. Most previous attempts were bordering on experimental, while Cazza appears to have organized the process into a proper business. More on that in a moment.

The technology is quite interesting. You’d think it’s a simple process, as the pumped concrete merely has to be routed to the appropriate position by the robot arm, but there’s so many things to be concerned with in this approach.

Consider that standard 3D printers have an immense advantage in that they “know” their positioning in absolute terms due to the fixed nature of their design. The extruder is perfectly (or should be) aligned with the print surface, and the bounds of building are explicitly known.

That’s definitely not the case on a building site, and especially with an extruder that is mounted on a mobile platform. While the robot arm introduces several axes of movement, they are known and easily controlled. What’s less known is the position of the mobile unit and its orientation.

Surprisingly, Cazza says the build site should be flat and level. They say:

While not necessary, it is helpful if the terrain is level.

This tells us something important about their system: it can somehow determine its orientation and position, even on irregular terrain. This is critical, as the mobile unit would have to move around to the “other side”, for example, to resume a print. If not done precisely, the print would fail. Somehow Cazza has figured out how to do this.

I suspect they have some type of vision system, as their material suggests they have been using AI techniques. It’s also possible they may set up some type of pre-positioned markers that are recognized by the system, much like is done for certain types of 3D scanners. Cazza says they have an accuracy of 0.1mm, so this is obviously a key feature of the system.

But once set up, the concrete extrusion proceeds quite quickly. They say the print speed is around 400m per hour, or about 100mm/second. But remember that the extrusion in this case is very coarse, otherwise extruding a building would take a very long time.

I should point out, as I always do with 3D printed construction ventures, that only the concrete is 3D printed; the remainder of the structure is made using conventional means. This implies that you must have contractors show up on site to install plumbing, electrical, windows, doors, insulation, paint, flooring, etc. And even during Cazza’s printing process, you must have workers on site to swiftly install cabling or other non-3D printed bits at appropriate moments when the machine pauses.

The two units current being marketed are pricey, with starting prices at USD$480,000 and USD$620,000. While this is quite a bit more than most 3D printers cost, it is in the range of expensive construction equipment, which is the intended market.

Cazza is set up to sell these units and provide consulting on project proposals, but apparently they also have lit up a franchising system. This, to me, makes sense, as local building contractors worldwide could then consider adding this functionality to their already sophisticated construction operations.

Why would they do so? Aside from the buzz of 3D printing buildings, Cazza suggests they could find lower use of materials, faster job completions and increased safety due to lowered labor requirements. I believe some of that is certainly true, but there are a couple of challenges they’ll have to overcome.

First, building methods vary considerably across the world, as construction approaches have evolved over centuries to incorporate local materials and account for regional environmental conditions. Technically, the 3D printed designs used by Cazza equipment will have to adapt to conditions.

There are also plenty of non-technical challenges, including certification of completed structures by local authorities, and in some cases, trouble with unions or even mobsters as their crews and activities may be affected.

Finally, the biggest challenge will be in the designs deployed with this technology. What are the best designs possible, if one removes the normal building constraints with 3D printing? We’re starting to learn what this means in the aerospace, medical, prototyping and automotive industries today, but no one has yet figured this out definitively for building construction.

But you have to start somewhere.

Via Cazza