A research paper this week describes an incredible new and very rapid 3D printing process, but it seems there may be challenges in implementing it.

The new “Volumetric 3D Printing” process, developed by researchers at LLNL and several other engineering universities in the USA, apparently is able to form entirely complete 3D objects in a single operation, which they call “unit printing”.

To me this is a fundamental step forward: you might call extrusion or laser-based 3D printing processes “one dimensional”, as only a single point of the object is being created at any given instant.

The next step was to 3D print entire layers of an object simultaneously, as has been done with several resin-based approaches where the surface of a photopolymer liquid resin is exposed to a complete layer pattern; in that scenario the resin layer solidifies all at once. That might be called “two dimensional” 3D printing.

Now, Volumetric 3D Printing could be “3D 3D Printing”, if I could use that awkward descriptor.

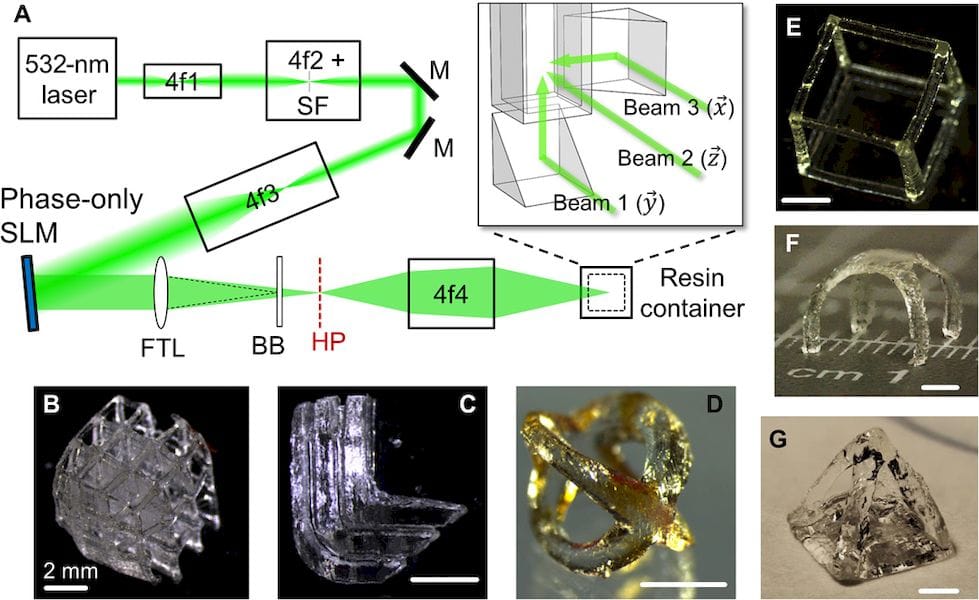

Here’s how it works: the researchers built a 3D tank of photopolymer resin, and then a 3D holographic display system illuminates a 3D pattern within the resin. The shape solidifies simultaneously in all three dimensions.

Using this technique might be unbelievably faster than conventional 3D printing processes, although their research seems to show otherwise.

But it’s not quite as simple as exposing the resin to the holographic light pattern. There is a key problem in that the photopolymer resin will normally solidify when photons impact it on the way towards their designated 3D target, solidifying the entire chamber.

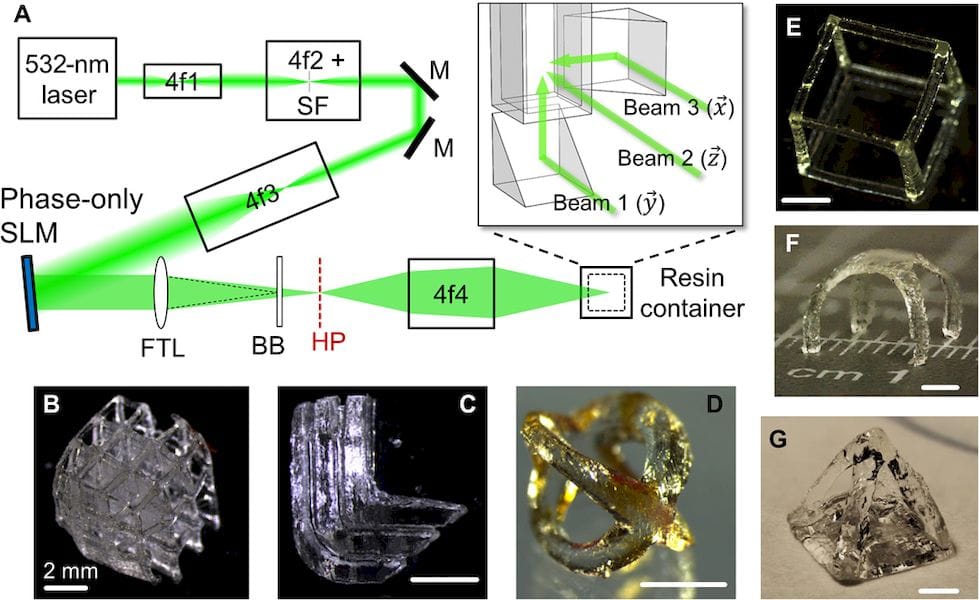

To overcome this, the researchers doped the resin with a very precise quantity of O2, which inhibits the photopolymer reaction. I say precise because you DO want the resin to solidify at the correct position. This is accomplished by having multiple lasers project the 3D holographic image, and the intersection points receive more energy than the non-intersecting points.

This energy deposition method is similar to medical radiation treatments, where tumors are targeted in this way.

As you can imagine, the ratio of O2 to resin is extremely critical, as is the time of exposure. If too long, then non-target areas solidify. If too short, then you have a fragile print. They must also balance the viscosity of the resin, which determines the flow of the inhibitive O2 with the fluid. This complex balance is effectively what determines the final resolution of the print, as the solidification can “soak” a bit further away from the target point as the exposure continues.

There are other challenges: A complex geometry would no doubt result in overlaps in areas that are not targeted. But the researchers found a way around this, which is quite ingenious: use multiple exposures within a resin tank to gradually build up the object, from the inside out. This is also commonly done with laser cutters when overlapping cut-outs must be made.

The speed can be quick: they say an exposure from 1 to 25 seconds can complete an object, although they seem to be experimenting with rather small build volumes. I don’t know about you, but pulling an object out of a resin tank in less than a minute sounds extremely attractive!

The researchers also mention in their paper that it may also be possible to build such a system using LED light sources instead of lasers, thus potentially lowering the cost significantly.

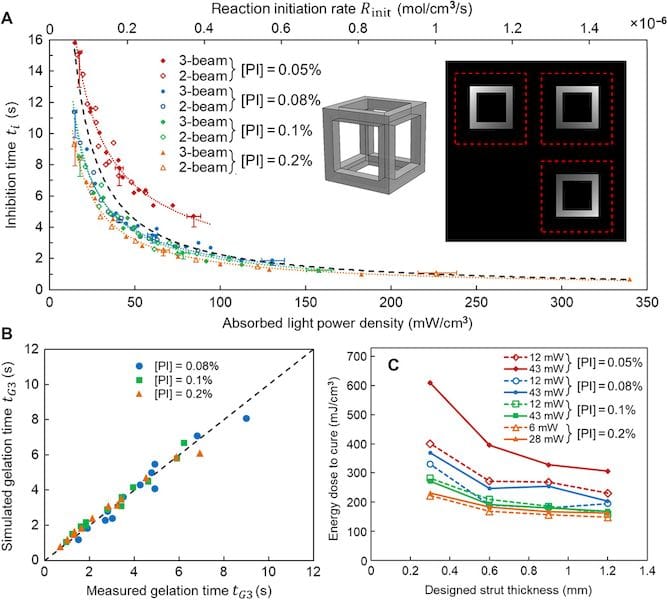

The researchers published a chart showing the speed comparison of the volumetric process vs. Other common 3D printing processes. Surprisingly it is not dramatically faster than certain existing processes, such as Carbon’s CLIP. However, I suspect that this is simply because they are at an experimental stage where the objective was to make it work at all, not make it work fast.

That comes next.

Could this become a major player in the set of 3D printing processes of the future? Perhaps, but it seems to me there is a great deal of work to be done yet to develop this approach. While promising, they must address the issues of scale, tuning for different engineering properties, tuning for reliability, testing of different resin types, redesigning for lower cost, and much more.

But it is certainly very promising and perhaps the most notable research on 3D printing I’ve seen this year.

Via ScienceAdvances