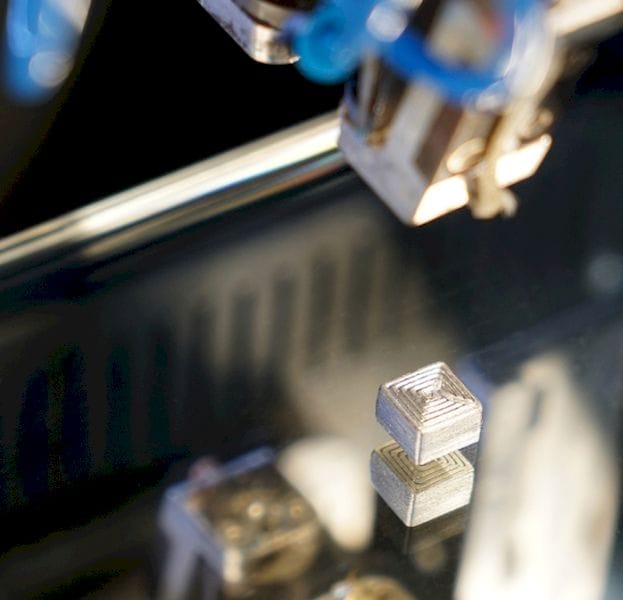

![A much harder metal 3D print made from special filament [Source: Fraunhofer Institute]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a4dfb309a.jpg)

Researchers at the Fraunhofer Institute for Ceramic Technologies and Systems (IKTS) have found a way to make much harder 3D prints in metal.

While much of the current industry metal 3D printing focus is on the larger commercial metal 3D printers from companies like EOS, 3D Systems, SLM Systems and GE, their processes are quite expensive compared to other forms of 3D printing.

Some companies have developed methods of 3D printing metals using less expensive processes. Typically the process is to re-use knowledge from the thermoplastic processes involving filament extrusion. Metal particles are mixed with thermoplastic resin to form a composite filament, which is 3D printed in the usual manner.

This creates a “green” object that is mostly unbound metal particles but with a significant portion of thermoplastic. Chemical or heat processes then evaporate the thermoplastic, leaving a structure of metal particles, the so-called “brown” part. A sintering session then binds these metal particles together into a final metal part.

This “cold” metal printing process has been adopted by several companies, perhaps most notably by Desktop Metal, who have gained huge followings of clients hoping to achieve metal 3D printing at lower cost.

However, the parts produced by this process are typically not as strong as those made with the powder bed fusion approach of EOS and others. This has limited the use of cold metal 3D printing parts.

One important use for metal 3D prints is tooling. However, tooling by definition requires parts made from very strong and hard materials, lest they break when in use.

Now Fraunhofer’s IKTS seems to have found a way around this issue, at least partially. Their experiments have revealed that by using much smaller metal particles in the composite filament they can achieve harder prints. They explain:

“During FFF, 3D bodies are manufactured from a flexible, meltable filament. For decades, Fraunhofer IKTS has got a proven powder metallurgical expertise. Thus, it was possible to produce the filament required for the FFF from hardmetal powders with organic binders. Depending on the materials structure, a reduced grain size and binder content can be used to specifically increase the hardness, compressive and flexural strength of hardmetals.”

Dr. Johannes Pötschke of IKTS says:

“The filaments can be used as semi-finished products in standard printers and, for the first time, make it possible to print hardmetals with a very low metal binder content of only eight percent and a fine grain size below 0.8 micrometers and thus allow extremely hard components with up to 1700 HV10.“

[HV10 is a specific engineering test to identify the hardness of sintered metals.]

This is a significant development, and it appears the solution is not nearly as challenging as one would have thought. This discovery could quickly lead to a number of highly competitive 3D printer filament manufacturers to develop their own form of a “super-hard metal filament”. However, it’s likely that IKTS has patents pending on the process and the specific materials involved.

There is another possibility: the manufacture of very fine metal powder for 3D printing is a tricky process mastered only by a few companies worldwide. These companies will certainly have stocks of such fine metal powder – which could be used to mix with polymers to produce a theoretical hard metal 3D printing filament. It’s not the business they are in now, but perhaps this could be another product line for them?

A research thesis details the incredibly complex world of volumetric 3D printing. We review the highlights.