![An experimental device capable of 3D printing in Kapton [Source: Virginia Tech]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a25e0200e.jpg)

Researchers have developed a practical method of 3D printing the powerful Kapton material.

Kapton is almost always found in thin sheets, and is used for insulation. In 3D printing it’s most often used as an adhesive solution for ABS prints by covering the print surface, or as an insulate cover for hot ends.

But no one 3D prints Kapton.

It would certainly be a good thing if it were possible, as Kapton is a very powerful material. It’s a polyimide developed by DuPont in the 1960s and is produced almost always as a film, hence its current use in 3D printing.

The material has several notable properties, including its incredible ability to resist almost all environmental risks, including many chemicals, UV light and electrical current. It also boasts a ridiculously high temperature resistance of 550C, far, far higher than any other commonly used polymer.

If only you could 3D print objects in this polymer. They could be used in outdoor, high-heat scenarios and many other situations where current materials used in 3D printing would fail miserably.

Now, it seems that you can, according to researchers at Virginia Tech, who have developed an interesting process for 3D printing Kapton they call “direct ink write”, or “DIW”.

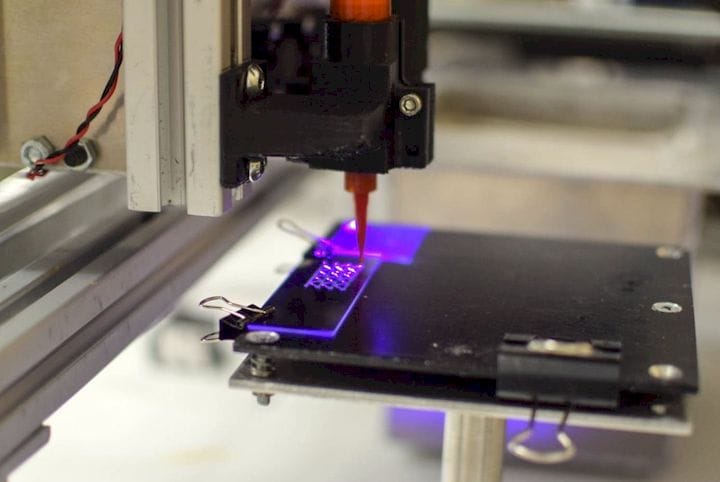

The process appears to mix small Kapton particles with a solvent into a paste. This paste is then extruded using a more-or-less conventional 3D printing three-axis setup into desirable shapes.

As the paste emerges from the nozzle and is deposited, a UV light cures the polymer into a solid.

After printing a separate process is undertaken to remove the solvent from the print to reveal a pure Kapton part.

![A 3D printed Kapton structure after removing solvent [Source: Virginia Tech]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a25e367b8.jpg)

This process is somewhat reminiscent of the “green brown process” used by several 3D printing companies to, for example, 3D print metal or ceramics using an extrusion technique. The “green” print is purified and then sintered to prepare a truly metal part.

But the Virginia Tech researchers have done something similar using polymers only. They say that the resulting parts have the same characteristics as real Kapton to approximately 400C temperatures. The deformation temperature is also very slightly less than 550C as well.

But functionally this DIW material would be essentially identical to Kapton.

Imagine designing a 3D printer that would extrude Kapton using conventional 3D printing technology. You would have to have an extruder/hotend that would reach a ridiculous 600C, and have a heavily insulated build chamber to hold it all. That would be terribly expensive, while the DIW process is vastly simpler.

This is quite a development, as this now enables the production of very high-temperature 3D printed parts that otherwise would have been ceramic or metal.

Of course, this process is only research at this point, but it seems to me that it is sufficiently powerful that someone is likely going to commercialize it quickly.

Via Virginia Tech

A research thesis details the incredibly complex world of volumetric 3D printing. We review the highlights.