![Microscopic view of a cavity in a metal 3D print [Source: CMU]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb09b32af548.jpg)

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University have discovered a fundamental issue with the most common form of metal 3D printing.

Metal 3D prints produced with the popular powder bed laser fusion approach are most often used for production purposes, as the material is identical to that which is used in the final parts. But because production parts are being produced, the scrutiny of quality is vastly higher than that for prototypes.

You wouldn’t want your aircraft to fail because of a flaw in a metal 3D print, would you?

That has been the pursuit of many metal 3D printing companies: to produce 3D prints that are flawless. Seemingly minor defects can, in some cases, cause catastrophic failure of the part and the associated assembly.

To date most companies have been experimenting with factors they can easily control, such as the quality and type of input material powder; the strength, speed, and orientation of the laser; and the environment in which the printing takes place.

Much of the work on this issue by 3D printer manufacturers has centered around monitoring the meltpool, a kind of transitory liquid volume that follows the trace of the laser’s path through the powder surface. The meltpool transforms the powder into a solid, fused mass of metal.

However, occasionally this doesn’t happened quite as is planned. Small gaps, or pockets of gas, can occur, introducing points of weakness in the print. Sometimes these are very difficult to detect after the print is completed, as they may be embedded within the print — yet still affect the strength of the part.

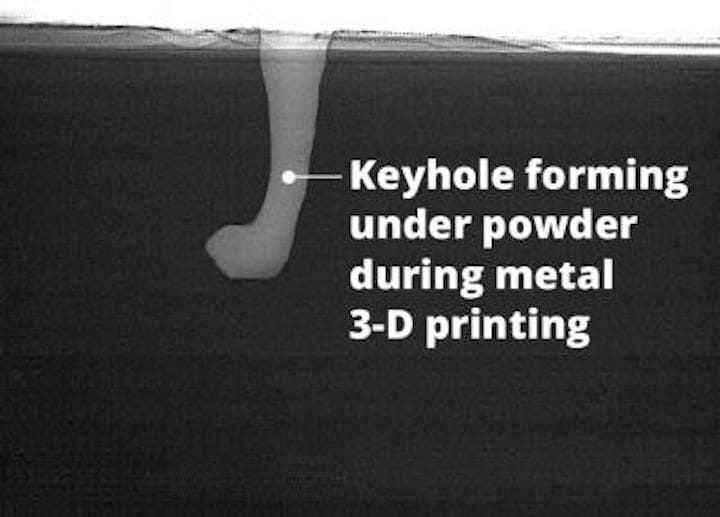

The researchers seem to have figured out how do these gaps are actually produced. They did this by observing the meltpool process in great detail by capturing an ultra high-speed video of the process using an X-ray device.

This is their major discovery: the laser is actually not simply melting the surface powder; it’s actually drilling into the powder! Of course it is not drilling very far, but sometimes these drill paths are not properly solidified, thus creating the cavities.

Another key finding from the researchers was that these gaps appear under virtually all operating conditions, meaning that the experimentations of 3D printer manufacturers to eliminate them are essentially fruitless.

However, this research does uncover the root cause of this phenomenon, and should allow engineers to step back and adjust machine designs to reduce or hopefully eliminate such gaps entirely. When they do so we could see a dramatic increase in the quality of metal 3D printed parts.

Via CMU

A research thesis details the incredibly complex world of volumetric 3D printing. We review the highlights.