We’ve long known that 3D printing technology was going to continue improving, even after the bubble of 2014, but it continues to be exciting to watch these developments unfold.

Seeing the technology get faster and bigger is particularly fun for the inner Tim “The Toolman” Taylor in all of us.

High Area Rapid Printing (HARP) 3D printing from a startup called Azul achieves both of these capabilities, producing objects 20 times the size and at 100 times the speed of some 3D printers. This results in 2,000 times the throughput of the most common industrial 3D printing technology.

To understand how this is possible, we reached out to Azul CEO and cofounder James Hedrick.

The Birth of HARP

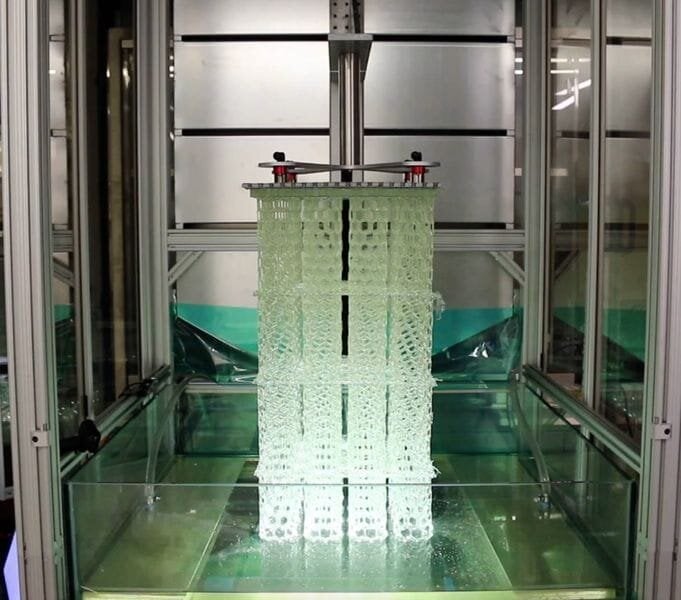

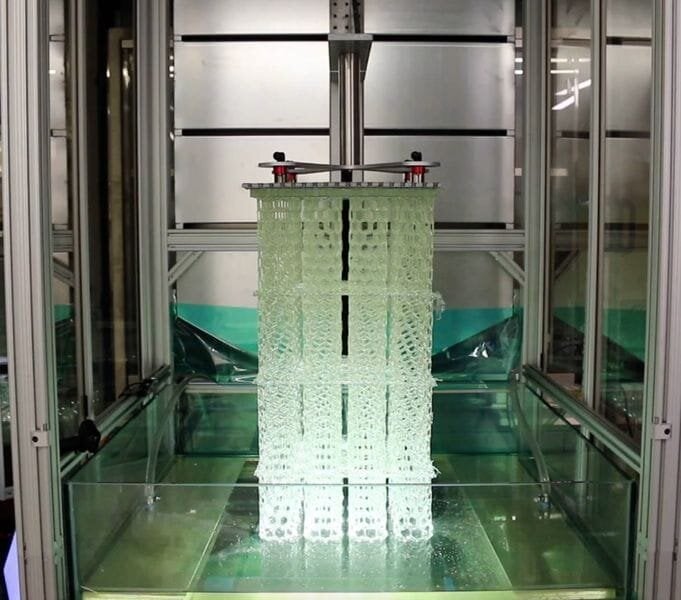

HARP is a patent-pending form of digital light processing (DLP) that projects ultraviolet (UV) light to cure photopolymer resin. Azul’s first 3D printer featuring HARP technology stands at a massive 13 feet tall and can print up to half a yard per hour. Surprisingly, however, the process wasn’t developed with such a large scale in mind.

At the lab of Northwestern Chemistry professor Chad Mirkin, the team that would go on to establish Azul was actually aiming to 3D print tiny objects, according to Hedrick. “This project started with the intention to develop the world’s smallest 3D printer with nanometer resolution,” Hedrick said. “When we learned the obstacles facing 3D printers today, we applied our technology to a completely different scale to solve the problem. The biggest obstacle was the learning curve when going from studying printed parts that are too small to see, to fabricating a printer that is twice as tall as you are.”

What may be more impressive than the sheer size of the HARP 3D printer is its speed. Though the HARP system is 20 times larger than a standard DLP printer, it prints at 100 times the speed of a standard stereolithography (SLA) printer. This combines to give HARP a throughput that is 2,000 times greater than industrial fused deposition modeling, the most common 3D printing technology found in industrial settings today.

How Does HARP Work?

Of course, the technologies chosen by Azul for comparison help beef up HARP’s numbers, as SLA is much slower than DLP and FDM is slower still. Nevertheless, those numbers are impressive. So, how does Azul pull off such neck-breaking speed at such a jaw-dropping size?

Traditional forms of SLA and DLP cure resin onto a print bed before a mechanism is used to detach the print with each layer printed. To improve speed, newer forms of continuous DLP rely on specialty techniques to render this mechanical cleaving process obsolete. Carbon, for instance, uses an oxygen permeable membrane (which the firm refers to as a “dead zone”) to ensure that its continuous DLP technology can continuously UV-cure resin without the need to repeatedly detach the print from the bed.

Read more at ENGINEERING.com