Josine Beets, Coastruction’s Project & Business Development Manager, on restoring ecosystems, supporting clean energy and the future of the company.

With the acceleration of global warming and other factors like pollution and industrial fishing practices critically destroying and endangering coral reefs and coastal ecosystems around the globe, it has never been more critical to develop solutions that can help to restore these fragile yet incredibly diverse environments.

Fortunately, there are people and organizations who have taken up this challenge and are finding creative ways to not only save coral reefs and other coastal environments, but also usher us into a more sustainable, ecologically minded future. One of these organizations is Coastruction, a Dutch startup that is leveraging its own 3D printing technology to build aquatic structures that are designed for a range of restoration purposes, like promoting coral regeneration and wave dissipation.

Coastruction, which is celebrating its third anniversary this month, was founded by Nadia Fani, who has a background in computer science and 3D printing. Over the past few years, Fani has put together a dedicated team of eco-enthusiasts trying to build a better future, including Josine Beets, Coastruction’s Project & Business Development Manager, who herself has a research background in nano-biology and bioprinting. We had the chance to speak with Beets about Coastruction’s overall mission, its unique technology and the various coastal restoration projects it is participating in.

From Idefix to Asterix

Coastruction founder Fani started developing 3D printing systems in 2015. In 2018, she built a small desktop system, which eventually evolved into the Idefix platform, a standard-sized 3D printer that deposits water onto a print bed consisting of a mixture of sand and cement. “What we have is a powder bed 3D printer, with a box filled with dry material and then you deposit water selectively on each layer, which acts as a binder,” Beets says.

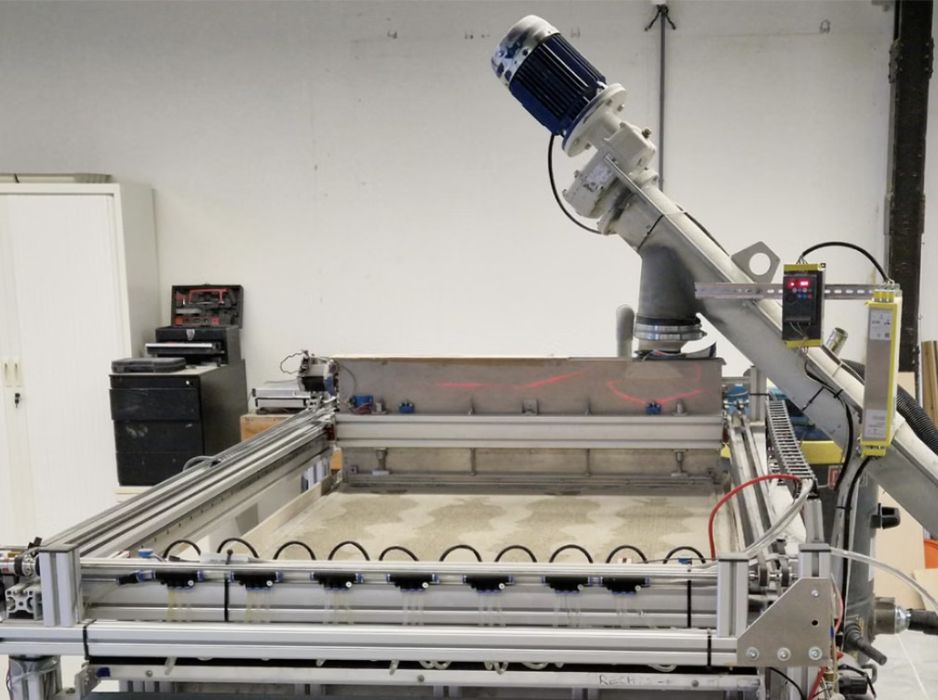

Since January 2024, Coastruction has rolled out the latest generation of its 3D printing technology, the Asterix, a larger system with a build volume of one-cubic meter. Instead of a single nozzle, like the Idefix, the Asterix is equipped with 88 nozzles that selectively bind the sand and cement mixture.

“Every layer the print bed lowers and a new dry layer is applied and water deposited,” Beets elaborates. “At the end, you have a big box filled with powder: some hardened and some loose. From there, you can remove the entire print bed (it is on wheels so can be transported and replaced easily) and set it to cure overnight.”

This initial curing process, which involves leaving the entire print box to sit for a night, ensures that the bound cement particles can settle and that prints are solid enough to be removed from the loose powder print bed and vacuumed. (The remaining loose powder can then be reused in a future build.)

From there, Coastruction’s production process involves placing the cement prints, which can measure up to a meter in size, outside, where they continue to cure. “The prints have to be moisturized,” Beets specifies. “So we pour water over the structures every day, like watering your plants, and after seven days, they are strong enough to be lifted by ropes and transported.”

In some cases, like in a recent collaboration with a team in Saudi Arabia, the curing process takes longer to ensure that the artificial coral reefs are strong enough to survive long journeys, like from Rotterdam to the Red Sea. “We’re also looking into building a large pool where you can leave the prints to cure an entire day in water,” Beets says.

The relatively simple process, which does not use any toxic materials, results in large-scale cement structures that can be deployed in coastal areas. In terms of the cement materials used, Coastruction mostly works with CEM I, consisting of 100% Ordinary Portland Cement, and CEM III, which is a mixture of OPC and blast furnace slag.

“We have found CEM III to be a good option in terms of its environmental footprint, but the structures also have to be stable, so we are researching the difference between CEM I and CEM III. Sustainability is also about durability and there is still a lot of R&D going into this and we are always looking for students who want to do their graduation project on material sciences to find the best and most sustainable materials.”

Designing for reefs

Of course, the printing process is only part of the equation: design also plays a huge role in what Coastruction offers and how its prints are welcomed into aquatic environments.

“We have two design experts that we work with,” Beets says. “Carlos Rego is our biomimicry expert and designer, and David Lennon is an advisor on artificial reefs. They work closely with us on each project, looking to ensure that our solution is suitable for each location. We also have Sam van den Oever, our engineer who knows exactly what does and doesn’t work for the 3D printer. For example, you don’t want to design something that would be too fragile, but you also want there to be enough holes for fish to enter into the structure. Additionally, if you want to lift it with a crane, holes for a sling can be incorporated into the design. It all depends on the situation.”

Read the rest of this story at VoxelMatters