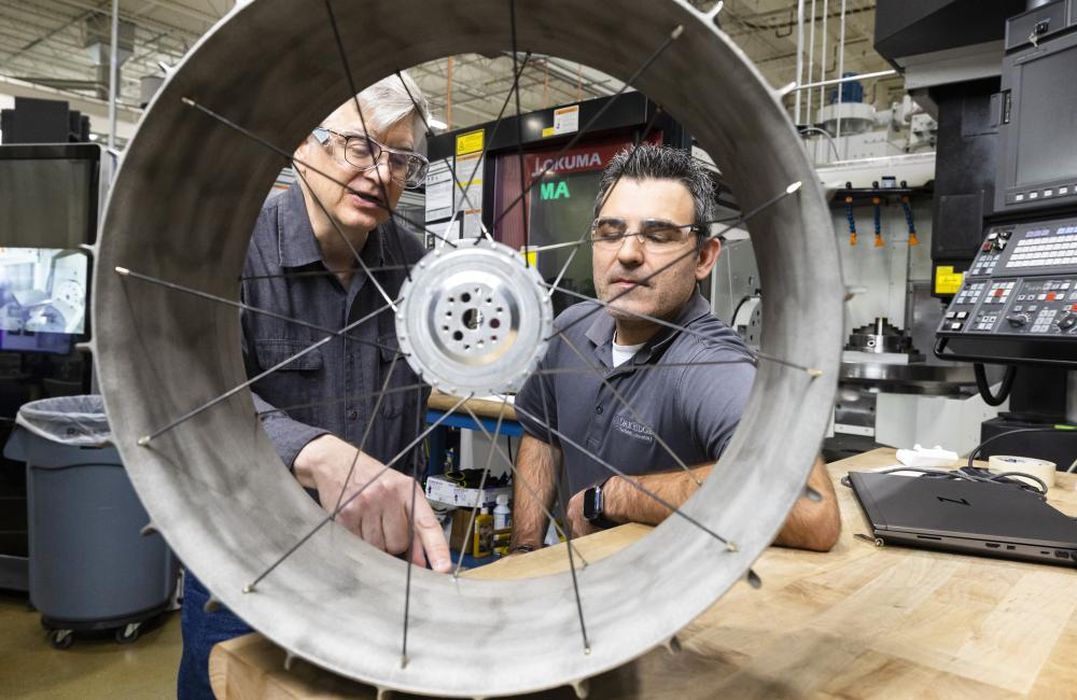

Researchers at ORNL have been 3D printing prototype lunar wheels.

ORNL, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, has frequently experimented with additive manufacturing applications for high-end science. Their work in this area has delved into nuclear and manufacturing domains, but now they are working on a lunar exploration application.

Interest in lunar applications has soared in recent years as the development of new inexpensive launch technology has enabled (or will soon enable) much more economic access to space. This in turn has triggered governments and entrepreneurs to envision new business and exploration activities taking place on our Moon.

The result is a bit of a scramble to rapidly develop a series of technologies to make that happen. One of them is how to get around on the lunar surface.

The Apollo astronauts used the Lunar Rover, but it had very limited capabilities and was not designed for long term use. Now NASA is developing a new series of automated rovers with their VIPER project (Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover). This machine is set to be sent to the Moon’s South Pole to determine the type and quantity of volatile substances, such as water.

There is a design for VIPER, but NASA wanted to see if the wheels could be manufactured using 3D printing, and they turned to ORNL for this purpose.

The wheel is seen at top, and it doesn’t look like a particularly difficult part to print. However, there are some unique challenges in this application.

You’ll note the wheel seems rather spindly, and the spokes are extremely thin. There are a couple of reasons for this: first, the wheel must be as lightweight as possible to lower transportation costs, and secondly the Moon has only 1/6th of the Earth’s gravity, so the wheel doesn’t have to be so robust.

That’s why it appears so weakly designed.

NASA was interested to see if a part could be made additively, which could drastically reduce assembly efforts and possibly increase part reliability.

However, the constant issue with LPBF metal 3D printing is the quality of the part. Minor miscalculations in the print parameters can result in print flaws and weaker metal microstructure that can disqualify a part from production use.

That’s critical when you realize that on the lunar surface these parts will have to withstand extreme temperature changes: in sunlight, temperatures will be up to +120C (250F) and at night down to -130C (-208F). That’s quite a bit of stress that parts must withstand.

That, I believe, was the key purpose of the exercise: can this type of part be reliably produced to the level of quality required for lunar operations.

If the work succeeds, then we could see subsequent generations of lunar system designs made right from the start with additive manufacturing in mind. Here the design was conventional, but more radical and perhaps more advanced designs could be considered if additive manufacturing became a certified method for this application.

Via ORNL