Researchers developed a system for cooking 3D printed chicken, but this might lead to improved print quality for other 3D printers.

The research by Columbia Engineering is quite fascinating, as they have developed a method for broiling chicken as it is 3D printed. In other words, a completed chicken print is actually edible at job end.

Their approach is to first grind down raw chicken meat into a slurry. The sloppy material can then be extruded with commonly available syringe extruders into basic shapes, layer-by-layer.

That part of the process is not new; 3D printed foods have been experimented with for over a decade, although the process has still not gained popularity due to long print durations and general weirdness of the approach.

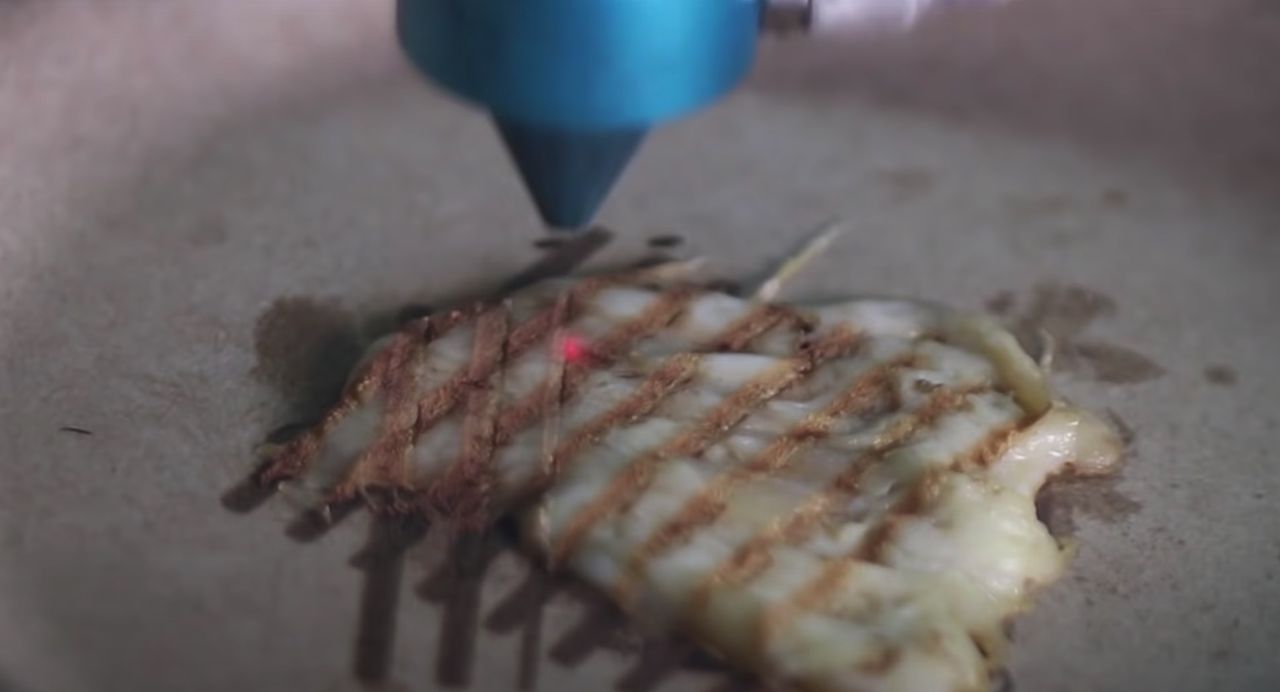

The new development is a laser system that can illuminate (or “broil”) each layer of chicken paste.

I know what you are now thinking: wouldn’t that result in dry, tasteless, chicken?

It does not because the lasers can be controlled very precisely. The exposure time, the laser motion and even the laser frequency can be changed. Through experimentation it is entirely possible to tune the laser exposure to cook the chicken to a perfect result, even better than human chefs could achieve.

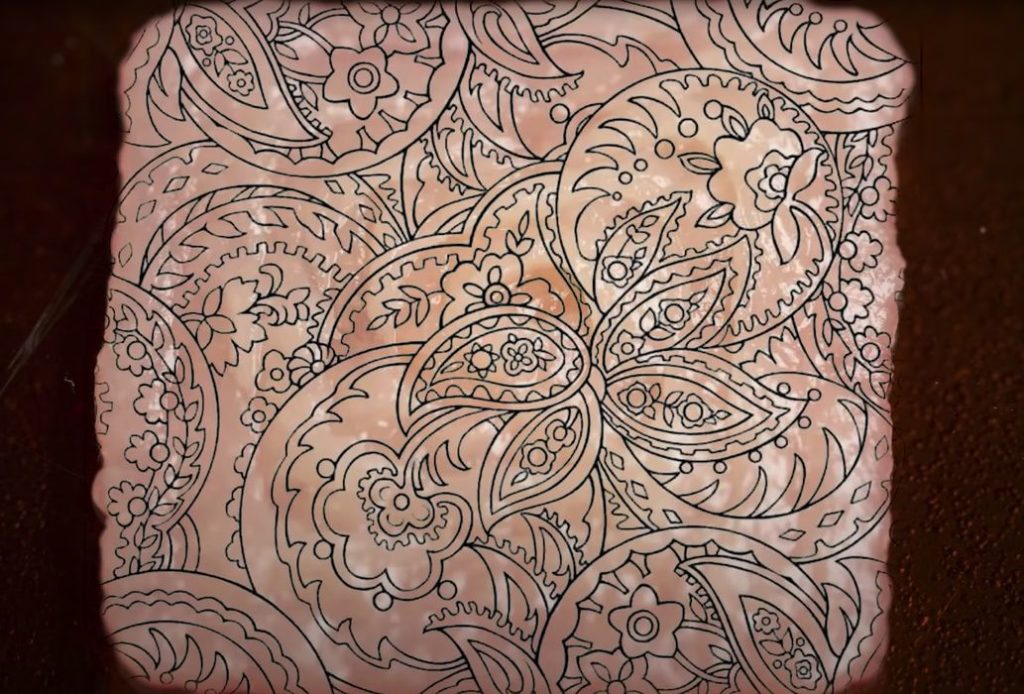

The approach also allows the laser to “engrave” patterns on the chicken surface, like this:

This capability can also be used to sear the chicken’s exterior in a way that is both attractive and delicious, as shown at top.

The researchers examined this unusual broiling process in several ways, eventually determining the best cooking patterns and laser frequencies. It turns out that the best interior cooking frequency is from a blue laser, while exterior searing is best done with an infrared laser.

You can see how the process works in this video:

I’m very impressed with this research, as it shows a method of food preparation not considered previously. In a way, it digitizes the cooking process that has been the same for millennia.

Layer by Layer Laser Treatment

However, there may be implications on “normal” 3D printing as a result of this research.

The researchers were able to “treat” each 3D printed layer with lasers in mid-print, something that might be applied to other materials.

Imagine, for example, if a typical FFF 3D printer extruding ABS, PETG or Nylon was equipped with this type of inter-layer laser system. After each layer was extruded, a pass by the laser could help fuse the material to a stronger state, particularly on the interior of the object.

Of course, this would require considerable tuning and software changes in addition to the laser hardware. However, it may be worth an experiment to see if there is value in this idea. Print times might be lengthened, but part strength could be increased.

Via Nature