As companies continue to explore the best ways to perform 3D metal printing, a question regarding materials has arisen.

There is extreme interest in 3D metal printing in the past year. We’ve seen General Electric scoop up several 3D metal printing companies and suppliers as there’s a bit of a scramble to establish dominant positions in an industry that’s set to explode. An increasing number of companies are gradually discovering how this technology can provide huge benefits.

But those benefits depend on proper use of the technology, and in 3D metal printing, there is much to discover.

Operators of plastic 3D printing equipment will know there are many tips and tricks for getting the most out of a 3D plastic printer, but the same – and much more – is true for 3D metal printing. However, due to the far fewer number of 3D metal printers, the discovery and adoption process has been slower than for plastic equipment.

One of the dilemmas encountered with 3D metal printing is the nature of the materials. Typically 3D metal printers use a very fine metal powder as the primary input material, usually titanium, nickel, steel, aluminum or other common metals. A powerful laser or electron beam sweeps across a flat bed of this powder to selectively fuse portions of the powder into solid objects.

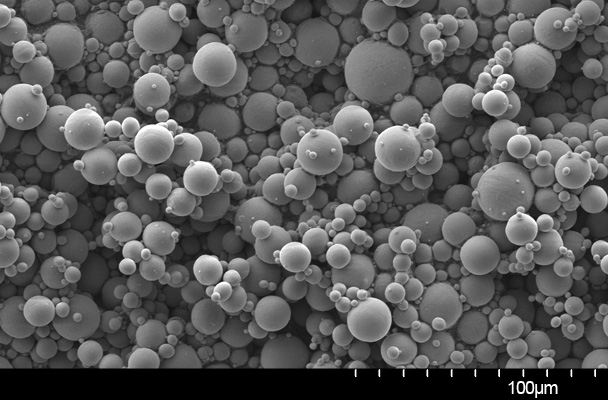

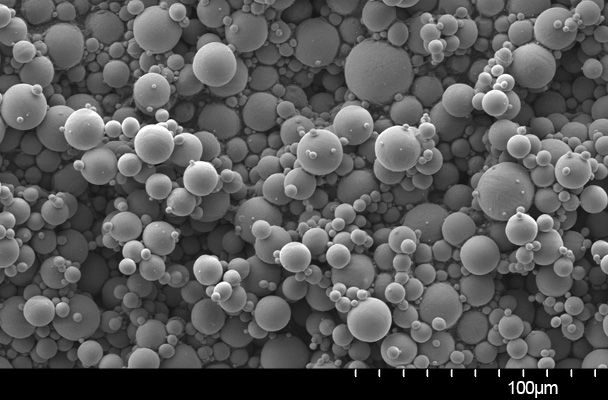

The question is, what size should the powder particles be? Obviously the spherical particles should be quite small and are typically in the range of up to 25 microns in size. A smaller size might result in a finer print, but at some level – usually the size of the laser or electron beam plus a nearby melt zone – the size doesn’t matter anymore.

But what might matter is the uniformity of the particles. Should all the particles be the same size? Or should they be of mixed size as shown at top?

One school of thought would be that uniform particles ensure a consistent surface finish.

Another school would believe that non-uniform particles when melted may form a superior crystalline structure.

But depending on the application of the 3D printed part, you might desire surface finish over strength. Or vice versa. You can also develop good surface finish through post processing – on some simple geometries, but not always.

The answer to this question, I’m afraid, is the now all-too familiar answer in 3D printing: It Depends.

Image Credit: Advanced Powders