Heralded as an important catalyst for the changing face of manufacturing and supply chains, additive manufacturing is back in the limelight.

It’s with good reason. The layer-by-layer additive techniques, clubbed under the umbrella term of 3D printing, are being extensively employed to help save lives as governments across the world battle to flatten the COVID-19 curve.

While companies like Isnnova and Lonati SpA have 3D printed valves for ventilators, others firms like RapidMade are now producing emergency personal protective equipment (PPE) such as lightweight plastic face masks with built-in removable filters as well as face shields. Groups like the Covid Maker Response (CMR) are also manufacturing, assembling and distributing 3D-printed PPE to health care workers on the front lines. CMR was founded by members of Columbia University Libraries, Tangible Creative and MakerBot.

Cloud-based 3D printing software has further given manufacturers the ability to easily make any part on demand, boosting the cause of additive manufacturing.

3D printing, however, is not just about plastic, although the story of 3D printing did begin in the 1980s with plastic, which remains the most widely used material. This is not surprising since plastic is readily available, comparatively inexpensive and well established in a variety of extrusion processes.

That said, 3D printers today also use metals, alloys and composites. These materials are being used not only to make PPE and other medical equipment, but also jewelry and toothbrushes, football boots, racing-car parts, machine parts, custom-designed cakes, human organs, houses and airplane parts, among countless other items.

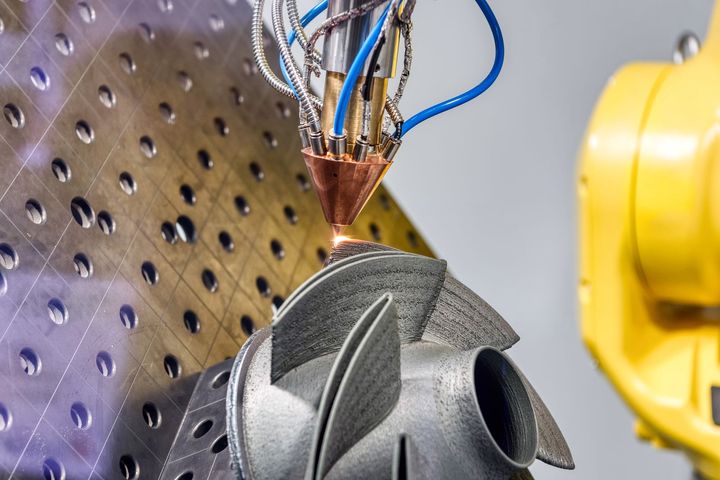

Metals and alloys such as aluminum, steel, stainless steel, gallium, titanium and cobalt-chromium are widely used in the aeronautics, automotive and biomedical industries, and use processes such as selective laser sintering (SLS), direct metal laser sintering (DMLS) or e-beam (EBM). 3D printers also use materials such as ceramics, sand, organic materials, marble, stone, and wood, depending on the applications.

The Power of Composites

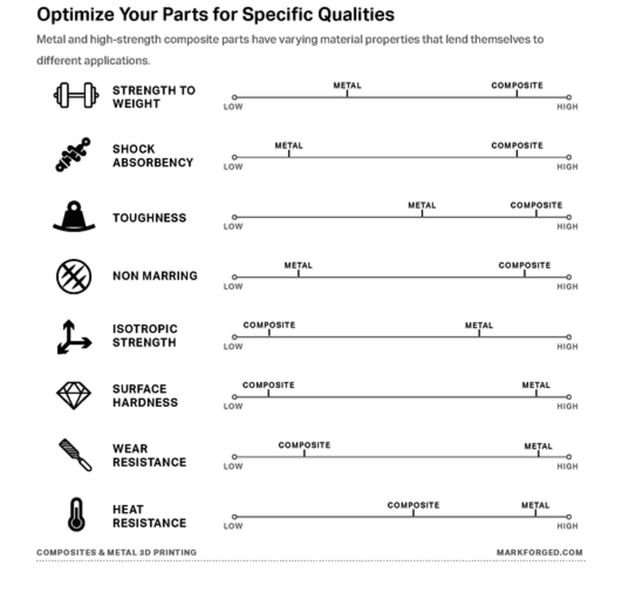

Composite and metal 3D-printed parts fulfil different roles on the factory floor and can complement each other to support production.

Using both a metal and a composite printer provides the flexibility to leverage the strengths of both materials and create extremely functional tools.

Composites, which are now getting their due in the field of 3D printing, can be broadly defined as materials that contain a reinforcement (such as fibers or particles) supported by a binder (matrix) material. The matrix provides a medium for binding and holding reinforcements together in a solid. Most composites offer significantly high advantages in terms of their specific strength (strength-to-weight ratio) and specific stiffness (stiffness-to-weight ratio).

Composites can be broadly classified according to reinforcement forms—particulate reinforced, fiber reinforced, or laminar composites.

Fiber-reinforced composites can be further divided as those containing discontinuous or continuous fibers. Fiber-reinforced composites, which contain reinforcements having lengths much greater than their cross-sectional dimensions, are considered to be discontinuous or short fibers if their properties vary by fiber length. Otherwise, these composites are considered to be continuous fiber reinforced[MG2] .

The percentage of fiber used and the base thermoplastic determine how strong the final part is. In the case of continuous fiber, long strands of fiber are mixed with a thermoplastic, like PLA, ABS, nylon, PETG and PEEK during the printing process. Parts that are 3D printed with continuous fiber are extremely lightweight yet as strong as metal.

Read more at ENGINEERING.com