Charles Goulding and Preeti Sulibhavi explore the potential impact of 3D printing on retaining women in the architecture business.

A provocative piece was published in the New York Times on December 15, 2018, titled “Where Are All the Female Architects?”, the question posed by Allison Arieff about why nearly half of architecture students are women, but so few remain in the industry post-graduation is an important one. Ms. Arieff rightly stated that even now, presumptions about women quitting to marry, being unable to command authority on jobsites, or even that their creativity was not on level, have somehow persisted in this industry. With men questioning their competency and qualifications or not believing they were actually in charge of an engagement, women do have the desire to be good architects with meaningful impact – however, they do not want to be recognized for being good women architects.

This raises a valid point: the architecture industry serves everybody, so why are architects who are also women identified by gender when they also represent the world they serve? Just as men do, female architects face the same technical architectural challenges – throw in the gender gap and some more hurdles get in the way. Maybe some of the answer does not lie as heavily in the gender gap as it does in the technology gap.

3D printing has had an invariable impact on various industries: medicine, sports, machinery and development, and even the food industry. The architecture sector is now well-positioned to benefit from the utilization of 3D printing and visualization. Women who have been underrepresented at these architecture firms can seize this opportunity and leverage 3D printing to address both the gender gap and the technical gap within the industry. 3D printing also has R&D tax credit incentives which can be of further benefit to these architecture firms.

The Research & Development Tax Credit

Enacted in 1981, the now permanent Federal Research and Development (R&D) Tax Credit allows a credit that typically ranges from 4%-7% of eligible spending for new and improved products and processes. Qualified research must meet the following four criteria:

-

Must be technological in nature

-

Must be a component of the taxpayer’s business

-

Must represent R&D in the experimental sense and generally includes all such costs related to the development or improvement of a product or process

-

Must eliminate uncertainty through a process of experimentation that considers one or more alternatives

Eligible costs include U.S. employee wages, cost of supplies consumed in the R&D process, cost of pre-production testing, U.S. contract research expenses, and certain costs associated with developing a patent.

On December 18, 2015, President Obama signed the PATH Act, making the R&D Tax Credit permanent. Beginning in 2016, the R&D credit can be used to offset Alternative Minimum tax for companies with revenue below $50MM and for the first time, startup businesses can obtain up to $250,000 per year in payroll taxes and cash rebates.

Utilizing 3D Printing in Architecture

Often, an architect’s first exposure to 3D printing is the creation of building models or designer furniture. Architecture firms, as well as those with interior design departments, often use 3D printing. Today, 3D printers are no longer limited to utilizing traditional materials such as plastic; now, materials such as salt, clay, sand, and cement are fair game in the 3D printing revolution. This variety can add to the flexibility and durability of architectural projects.

In Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello’s co-authored book Printing Architecture, various techniques, materials, and current projects are described in detail. The book was reviewed on Fabbaloo where it was lauded for providing aesthetic uses for 3D printing as opposed to merely adding to the structure or formation of buildings. While all elements of 3D printing provide value for architects, the functional and structural aspects can be of consequence for those looking to integrate 3D printing into mainstream architecture.

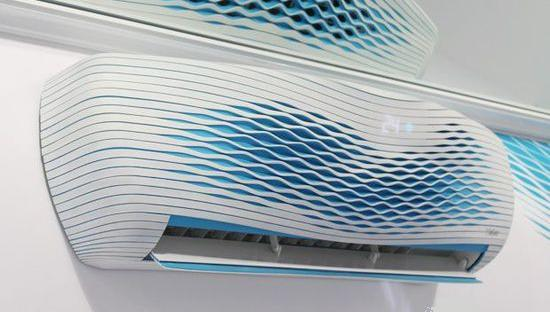

Architecture design structures include all aspects of a building envelope. The building envelope is defined as the elements on the perimeter of a building, including the roof, walls, windows, doors and foundation. Architects often work on heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) with engineers and it is crucial to right-size the HVAC system to the architect’s designed building envelope.

3D printing can assist in the HVAC static part development and replacement area. When an HVAC system stops working and personal discomfort abounds, 3D printed parts can make HVAC stronger, more durable, and more cost-efficient than ordinary parts. 3D printing would allow HVAC systems to be customized for unique applications by consumers as well.

While female architects may not have to reinvent the wheel, applying certain innovative principles and techniques of 3D printing technology to their industry may help immensely. 3D printing can use various materials and media to create unique and versatile objects. The opportunities can appear limitless with the endless array of variables to choose from.

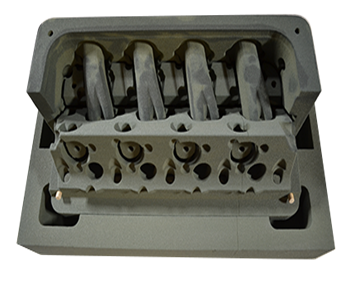

Sand

Utilizing sand to create components has a long history. Sand has further uses now, as demonstrated in the process labeled sand casting. Sand casting was traditionally used in the metal casting process whereby sand was used as the mold material and then patterns were carved directly into the mold cavities of sand. The traditional means for manufacturing sand cores and molds using metal inserts is no longer the most efficient or cost-effective method. Now the patterns are carved using 3D printing technology. 3D sand core and mold printing advantages include: higher accuracy of each sand core and mold; no tooling required; virtually unlimited design freedom; molds and cores are almost immediately ready for shipment after 3D printing; minimal post-processing of castings required due to reduced flash; and, it is more eco-friendly (Furan system versus a binding resin system). The particulate material in sand casting cores and molds is silica sand.

Cement

Cement is used in the development of concrete. In the late nineteenth century, concrete became a common building material and by the twentieth century, it had become a global material phenomenon. 3D printing with cement involves taking the laborious, skilled construction process out of pouring concrete. Currently, a variety of methods are used to 3D print concrete at construction scale. These methods include: extrusion and jet-binding techniques, contour crafting, and even developing robots to work alongside the 3D printers.

Among cement’s many uses is for shelters or homes, given its sturdy and durable qualities. It is estimated that 1.2 billion people in the world live without adequate housing, according to the World Resources Institute’s Ross Center for Sustainable Cities. One way to use innovative technology, such as 3D printing, is to apply it to address real-world challenges. ICON has created 3D printers, robotics, and advanced materials that can essentially build a single-story, 650-square-foot house out of cement in under 12 to 24 hours (not counting other construction aspects). This is a fraction of what it takes for new home construction. Partnering with New Story, a not-for-profit that addresses global housing needs, ICON is hoping to transform communities that face poverty and unsafe conditions. The first 3D permitted home in the United States is located in Austin, Texas.

On a more functional level, grab tiles made from cement were designed using 3D printers and with elder-care facilities in mind as a way of assisting residents to get up or in preventing falls. With deep and doubly curved surfaces the tiles are a means for interacting with them and can be used as handles.

Clay Cool Brick Masonry

The oldest artifacts crafted by man are often made of clay. That is why utilizing clay in 3D printing is a logical idea. Clay is a mix of alumina, silica and chemically bonded water, which makes it inexpensive and readily available as well.

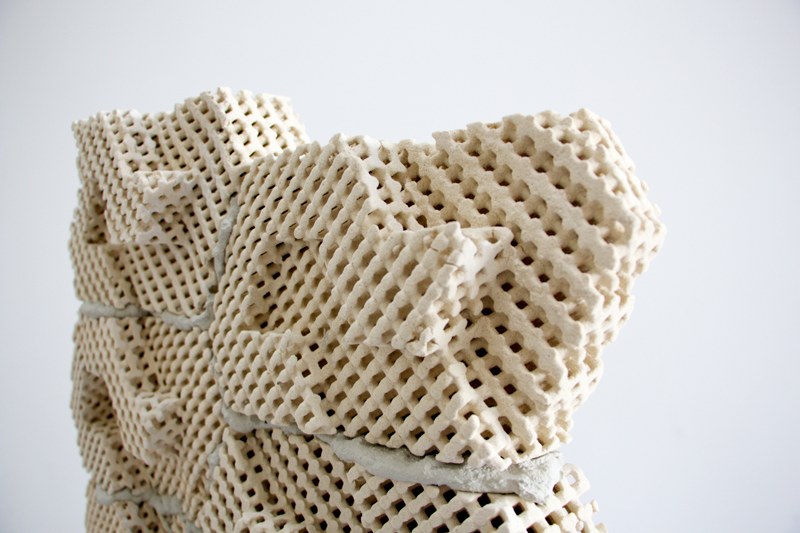

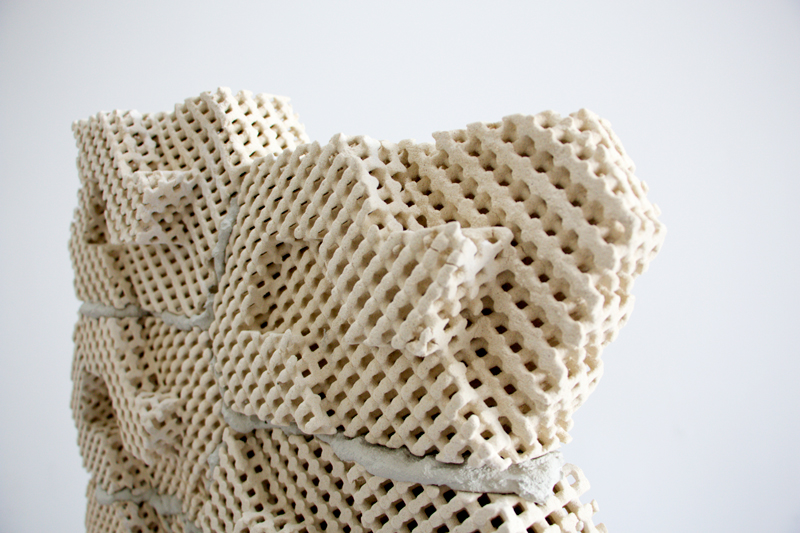

The Cool Brick is an example of utilizing the advantages of powder-based jet-binding printing technology (see image at top of article). According to Printing Architecture, the independent, creativity-driven, 3D Printing MAKE-tank, Emerging Objects, developed formulas and techniques for 3D printing clay, both with powder-based printers as well as with paste-extrusion 3D printers that use moistened clay. Inspired by the porous Muscatese evaporative cooling window designs of the Middle East, which are designed to keep living quarters cool, the Cool Brick masonry system collapses the ceramic vessel, wood screen and window into a single building component made possible with the help of 3D printing. This is also a form of maintaining temperature in a home and can be considered a form of HVAC.

Using 3D Printing to Fill the Technical and Gender Gaps

When answering the question, Where are all the female architects? looking to 3D printing might not be the obvious or comprehensive solution, but it is definitely one way to help fill both the gender gap and the technology gap. With so many techniques and materials to develop on, advancing architecture through innovative 3D printing provides a unique and invaluable solution. It also carries with it R&D tax credit incentives that can be utilized by firms ready to listen to women in architecture who can use techniques related to 3D printing in their work.

COBOD’s BOD2 construction 3D printer seems to be catching on as the company has made multiple sales of the new device.