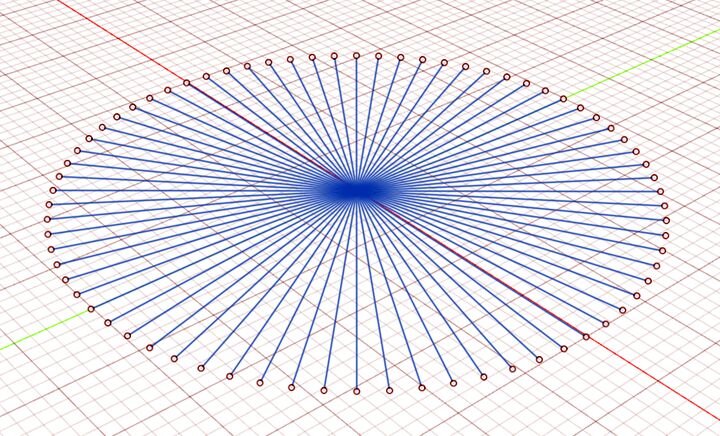

![Illustration of the density effect with volumetric 3D printing [Source: Fabbaloo]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/volumetric-density_img_5eb0509b1a882.jpg)

Earlier this week I posed some questions about the new volumetric 3D printing technology, and surprise, an answer showed up.

Volumetric 3D printing is a new concept in which rapid 3D printing is achieved by illuminating a rotating vat of photopolymer repeatedly, in a kind of “reverse CT scan” process. There are a couple of companies and researchers developing this technology, which hasn’t yet hit the market. You can read more about it in our previous story here.

It’s a fascinating process that is definitely the most rapid 3D printing method yet developed, as prints can be produced in literally seconds. If perfected, this technology could devastate many current 3D printer manufacturers and open up new opportunities where long print delays negated the use of 3D printing.

While obviously promising, there are many challenges. One of which I questioned was the potential requirement for use of transparent resins only. These would allow the illumination to traverse through the depth of the resin vat.

Another question I had was regarding the solidification of interior portions of the print. My thoughts were that as the exterior of the model solidifies, does that not prevent transmission of light to interior portions? Would we end up with egg-like prints with soft interiors?

Surprisingly, a good answer to my question arrived in our inbox. The submission was signed anonymously, but is clearly from someone who has thought through the puzzle of volumetric 3D printing. They say:

“Instead of slicing it horizontally, slice it vertically along the central axis ,

Project this slice onto a flat sheet of photopolymer coated film but not strong enough to trigger the photoinitiators chemistry fully.

Rotate your model,

Take another vertical slice,

Rotate the polymer coated film by the same number of degrees as the model,

Project this new slice onto a new virtual flat sheet of photopolymer

Now, envisioning the tank as a series of thousands of virtual sheets, consider the photonics.

Regions of the model closest to the axis will receive energetic exposure from a greater number of photons per rotation than the “outer surface” of the part. So we apply a dynamic mask to the projection which reduces the brightness or exposure time from the innermost “pixels” of each slice.”

[Editor’s note: See illustration at top for this concept. Notice how the density increases towards the center.]

“Now let’s just eliminate the word slice…instead it’s a movie of exposure brightness masked internal cutaways.

So long as the photoinitiator isn’t “triggered” but merely excited and maintained in an excited state on the edge of activation, you can time the voxel by voxel exposure, not only for the surface, but the interior as well. Once the object exists within an excited near triggered state, a quick finishing pass to push them over their trigger point can be made with minimal concern for intersecting with undesired “blank voxels”. In an unexcited state, having not been pre-exposed and stimulated, this “development pass” does not have enough energy to trigger them, only the pre-exposed voxels.

I am uncertain as to the specific chemistry being used by either of the cited companies but will offer in my own experiments that one alternative path to internal feature resolution can be to use a polymerization inhibitor that is broken by the first pass. This leaves a Gel like object that is highly photosensitive within a vat of low sensitivity resin. The second wave pass triggering photo-polymerization only in the pre-exposed (non-inhibited) resin.”

I hope this helps resolve some of your curiosities and confusion about the process. Again, I am not with either of the companies cited so my information and experience may be a beat or two off their work.”

That clears up some of my questions, and also raises more about the chemistry of the resins used in volumetric 3D printing. Clearly there is a lot more to be discovered here.

And a big thanks to whoever you are, mysterious submitter.