A road bike frame is a study in elegance and minimalism.

It uses the minimum amount of material but is rigid and strong. You’ll break before your bike does. Its diamond shape has not been improved upon in a hundred years. No better solution has been found to transmit the compressive and tensile loads from the ground and the rider. Its tubular members keep the bike frame in plane even when a thousand watts (the peak power of a Tour de France sprinter) try to twist it.

There’s simply nothing better to resist twist than a round cross section. As little as two pounds of material can support a 150-pound rider, even in a tight downhill turn, even if they hit a bump….

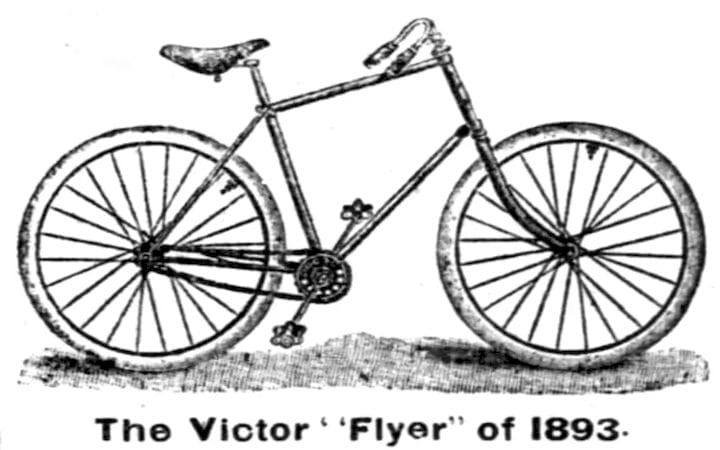

The bike frame as we know it—perfect as it may be—came into being without the benefit of CAD, simulation and certainly without generative design. The originator may have cut tubes to length, brazed them into lugs, and voilà! The diamond frame was born.

Sure, there were a number of design attempts that led to the diamond frame. Frame members may have been solid rather than made of hollow tubes. There were different materials used for bikes, including wood. Grainy black and white photos show many sub-optimum designs. The penny farthing, for example.

But have we thought of every possibility? Could there be a better design than the diamond, tubular frame? Have we settled on the diamond frame without doing design diligence? In our human weakness, we often assume the last solution is the best. We can stare at something long enough and convince ourselves it is the best way. We’re human. But is it optimum? Is it perfect?

Enter a class of design software that should, in theory, throw away the limits and restraints of human design, and not be bound by stock material on hand, like tubes; or joining methods, like welds; a very limited library of shapes, like round; or a few materials, like metal.

Generative design has the potential to explore design possibilities without bias, without limitations. It doesn’t care what looks good, if it is symmetrical, if it can be manufactured by any mortal means. Its sole raison d’être is to find an optimum solution, and being computerized, it can subject endless possibilities to discerning tests.

Read more at ENGINEERING.com

A manufacturing-as-a-service company has developed a way to 3D print continuous carbon fiber in a production setting.