I spoke with VELO3D’s Zach Murphree to find out more details on the company’s recent announcement of a tall version of their popular metal 3D printer.

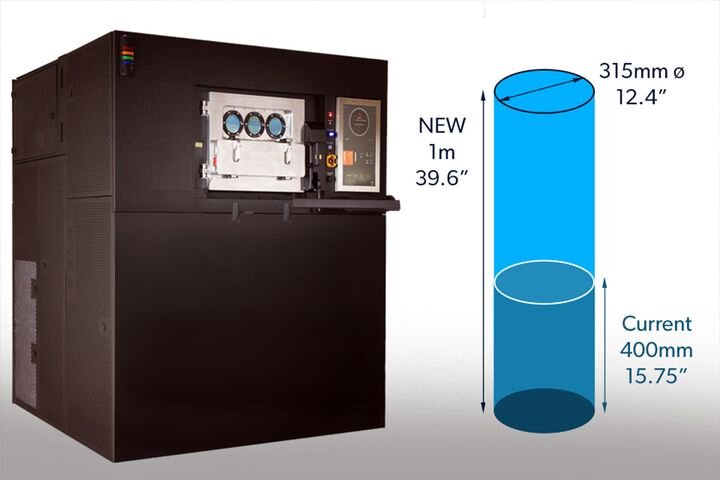

Last month VELO3D unveiled their second 3D printer, and it is quite similar to the original Sapphire metal 3D printer, except for one main difference: the build volume is much taller. While the original Sapphire’s cylindrical build volume is 315mm diameter by 400mm tall, the new tall version has a build volume of 1000mm tall with the same diameter, 315mm.

The new “1 meter” Sapphire is to launch later this year.

While “stretching” a 3D printer’s Z-axis is a relatively common practice among 3D printer manufacturers as it is usually technically straightforward, I wondered about VELO3D’s decision process. Why would they choose to do this particular upgrade?

Is it just as straightforward as making the build space larger, or were there other considerations?

It turns out there were.

Stretching A 3D Printer

Making a taller build volume is technically easier than changing other axes, as you would install taller guide rods and extend the build chamber upwards. Most other hardware would remain the same, and this is indeed the case with the 1 Meter Sapphire metal 3D printer.

VELO3D had been contacted by several clients, specifically in the oil & gas and aerospace industries, about larger build volumes. It turns out these industries, or at least VELO3D’s specific clients, happened to have parts that exceeded the build volume of the original Sapphire 3D printer.

Through some research VELO3D was able to determine that many of their needs could be met by simply extending the build volume upwards to a one meter height. Murphree explained their original intention was to go to 600mm, but clients demanded a larger volume, hence 1000mm was adopted.

Without this extension clients would be forced to split their parts into at least two pieces and assemble them after 3D printing.

This is not optimal in several industries because when parts are assembled there are seams. Seams are potential points of failure, which in the oil & gas industry could be especially undesirable. Leaks of flammable material are not generally wanted.

In aerospace seams are equally undesirable, but for different reasons. Assembled parts require bolts and nuts to hold the pieces together, and those all add to the weight of the part. And it’s not just the nuts and bolts; there are lugs required to hold them, too. Heavier components are not only undesirable in aerospace, they are literally expensive as each gram requires more energy / fuel to place it aloft.

Thus there was clear demand for VELO3D to make a bigger metal 3D printer.

Tall or Wide 3D Printer?

If you’re printing a 1m part you have at least two choices: you can print it vertically or horizontally. VELO3D had to choose which approach to take.

Their choice turned out to be an easy decision, as the key factor was print quality.

VELO3D’s main claim to fame is the amazing print quality they can achieve on the Sapphire system. The parts I’ve seen from their equipment are incredible, with extremely fine details and very thin walls. They achieve these results by basically tuning the heck out of the system. The Sapphire device includes many sensors that are carefully monitored in real time. These allow for intelligent software adjustments to a variety of machine operations to achieve optimum results.

In other words, the Sapphire is optimally tuned for its specific build volume. Changing that build volume could knock out the tuning and require a lot of work to create equivalent tuning parameters.

VELO3D realized that by extending the build chamber vertically they could maintain the same 3D printing conditions — and tuning. The build “area”, a 2D plane of powder with a controlled atmosphere, would simply travel upwards farther than it normally does on the original Sapphire.

I asked whether they considered a horizontal extension instead, and Murphree explained that there were significant issues in doing so.

Evidently maintaining consistent gas flow is a notable problem on a wider print bed, and this would be the issue for VELO3D if they attempted a horizontal extension. This could compromise their quality and print consistency.

But with the vertical extension, they were essentially able to re-use almost all of their existing tuning approach. It was also therefore faster to develop and will hit the market earlier.

Murphree also explained VELO3D currently offers several metals in their equipment, and are adding a few more. Apparently they’re working on nickel superalloys at the moment.

These moves are all aligned with VELO3D’s ongoing strategy to gradually widen their product breadth to open up the possibility of marketing to more clients.

So far, it seems to be working.

Via VELO3D