![Microstructures revealed with and without ultrasound treatment [Source: Nature]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb08bfa1033e.jpg)

New research has developed a method by which 3D printed metal parts can increase both tensile strength and yield stress by twelve percent by using ultrasound.

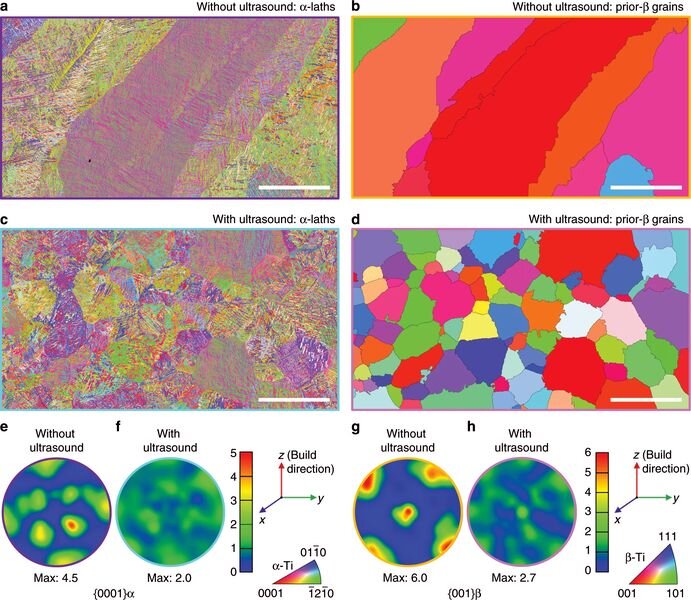

The research, undertaken by RMIT University in Australia, focuses on the orientation of grain structures within 3D printed parts. This microstructure is a key factor in determining the ultimate strength of a part produced by any manufacturing method.

Poor 3D Printed Microstructure

The issue is that during metal 3D printing using the standard powder bed / laser approach, the microstructures tend to line up along the laser path in columnar grains. This is because the surrounding material is thermally quite different, and the material tends to bind with hotter material recently fused.

3D printer manufacturers and operators have long been aware of the need to create optimal microstructures, but have had very limited means to do so. Much of the effort to date has involved tuning the materials, temperatures during 3D printing activity, and most importantly post-process treatments. These do improve the strength of the printed parts to some degree.

Poor microstructures often result in anisotropy, an effect where the strength of the part varies depending on the direction measured. That’s generally not good for production parts that must undergo mechanical stress. In some cases, parts are 3D printed by experienced operators in a way to ensure the expected stress happens to line up with the resulting microstructure to minimize problems.

But that’s just black magic trying to overcome a limitation of the machine. Really, the machine should produce isotropic parts that are strong in each direction. However, that requires the microstructure to be oriented properly and uniformly.

That’s the problem the researchers attempted to solve, and it appears they did.

They explain:

“Here, without changing alloy chemistry, we demonstrate an AM solidification-control solution to printing metallic alloys with an equiaxed grain structure and improved mechanical properties.”

In other words, they were able to avoid the creation of long columnar grains along the build path, which should result in increased isotropy.

3D Printing Using Ultrasound

How does this work? It all focuses on the process of nucleation, the method by which crystalline structures begin when molecular components happen to align.

In traditional 3D printing approaches there has to be nucleant particles present to act as “seeds” for the crystal structures to form. Some materials don’t have these naturally and other nucleant particles must be introduced, but sometimes that messes up the chemistry and strength of the material.

![Ultrasound method for 3D printing [Source: Nature]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb08bfa58f16.jpg)

The researchers found that by blasting the material with high-energy ultrasound, they were able to create cavitation and microscopic bubbles. These extremely short-lived bubbles will implode, causing tiny shock waves. The shock waves travel through the neighbouring material and jitter the molecules and thus create many more opportunities for nucleation events to occur.

Isotropic Parts

The result is the absence of long columnar microstructures found in typical additive manufacturing operations. Instead, they found the crystals of shorter and near uniform length. This allows the resulting parts to have greater isotropy and thus greater general strength.

The researchers began their work with Ti-6Al-4V, and were successful. Then, they were able to repeat the results using other materials, including Inconel 625, and:

“… expect that this method may be applicable to other metallic materials that exhibit columnar grain structures during AM.”

Their method was to place a sonotrode under the build plate and introduce 20 kHz sound waves toward the build path. This seems like a rather simple addition to a metal 3D printer design, and while the project is just research at this point, I would imagine several metal 3D printer manufacturers would be extremely interested in this process.

It’s therefore likely we will eventually see ultrasound add-ons to metal 3D printers in coming years, and all enjoy the stronger parts that emerge.

Via Nature