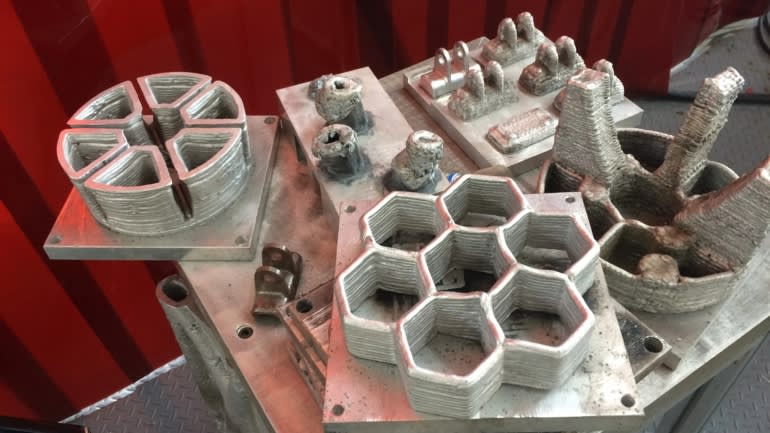

![It looks like Pix is using DED for metal 3D printing, from the looks of these parts from its factory in Guiyang [Image: Coco Liu / Asian Review]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CocoLiu2_img_5eb08f358b216.jpg)

Global trade and increasing tariffs are major topics of discussion these days — and 3D printing is increasingly a part of that conversation.

Trade wars, tariffs, changing regional relationships: there’s a lot going on on the global policy stage. We’ve been seeing talk of 3D printing rising as the technology proves itself out as a viable manufacturing process, and it’s coming into the picture of trade wars as a potential solution to get around rising costs in the supply chain.

Most of the talk has been theoretical up to this point. Could 3D printing be a way to avoid tariffs?

Theoretically, sure. Additive manufacturing has a major benefit in localizing production, and increasingly often suppliers are talking about how a design created in one country could be emailed to a production site in another to physically create the exact same part on another continent.

Sounds great. But again — it’s been mostly theoretical. There remain a lot of questions in using 3D printing to overcome tariffs on overseas products.

Pix Moving

Today I’m reading an article about a company that’s putting that theory into action.

China-based Pix Moving, Coco Liu and Shunsuke Tabeta of the Nikkei Asian Review write, is a vehicle manufacturer looking to 3D printing and generative design as solutions for the way it does business — overseas.

Pix Founder Angelo Yu is embracing advanced software and production methods to create new cars in a shorter timeframe.

This part of the story should sound familiar as the automotive industry as a whole is showing itself to be a major adopter of both generative design and additive manufacturing.

What’s unique here is the positioning. Because Pix is based in China — and indeed, outside of China’s major automotive centers — its business model needs a rethink given current circumstances.

We’re focusing mainly on the tariffs and the US/China trade war, but the Asian Review also points to the ongoing reduction in China’s workforce, which is certainly also an issue that can benefit from increased automation.

Pix is looking to do business with the US, but that’s no longer so easily done as it is said. So there’s something interesting at play, as Yu explains:

“We don’t export cars to the U.S. We export the technique that is needed to produce the cars.”

Advanced Automotive Manufacturing

![Angelo Yu, the Founder and CEO of Pix Moving [Image: Shunsuke Tabeta / Asian Review]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CocoLiu1_img_5eb08f35ddd66.jpg)

He’s working with this idea-export technique from experience, as Pix itself has benefited from this strategy. Guiyang is nowhere near Guangzhou or Shanghai, noted as China’s hubs of the automotive industry. This leads to supply issues — so Yu ensured that his team needed fewer individual supplies.

Enter generative design.

One of the oft-touted benefits of this design technique, and one that goes hand-in-hand with 3D printing’s of component reduction, is in fully rethought geometries.

Pix mechanical engineer Siddarth Suhas Pawar told the Asian Review he “would have never thought about making a car that way” — but the computer-generated designs are proving out their merit for what the team can physically create.

The Asian Review reveals:

“Take the chassis. AI cut the number of parts from thousands to hundreds. As so often happens with technology, however, solving one challenge created new ones.

Most of the needed parts were too unconventional to be procured from distant suppliers in Guangzhou and Shanghai. Yu’s team had to figure out how to print them. And not surprisingly, printing a whole car was far more difficult than a drone. It was not until late 2017, when Yu watched a YouTube video of Dutch engineers making the world’s first 3D-printed steel bridge, that he understood how the technology could be used to make larger-scale objects.”

That 3D printed bridge, by MX3D, proved an inspiration and proof of concept for bigger 3D prints. So with the understanding that large-scale 3D printing and AI-driven design are viable, it’s been off to the production races for Pix.

Global Trade / Local Production

With the process validated, Pix has been eyeing business opportunities.

A major step forward for the company comes in the form of two of its employees establishing a production site in San Francisco, where they can 3D print their car parts.

The first customer for the company is based in Texas, where a company wants an advanced, self-driving truck. Yes, “truck” — just the one. Another advantage Pix is working with here is the small-volume production capability of 3D printing, as the technology precludes the need for molding or building up large parts inventories to create economies of scale.

That step is a big one, with a current customer highlighting real market demand. The two Pix employees will work on US soil to produce parts designed by the home base team in China: no parts shipping required.

“The U.S.-China trade war will motivate more and more Chinese manufacturers to embrace smart manufacturing,” Yu told the Asian Review. “In the future, international trading will no longer run on cargo but on the cloud.”

The Texan company isn’t the only interested party; major automotive players Volvo and Honda have apparently also expressed their desire to draw Pix into their incubator programs. Pix is also involved in Autodesk’s well-known digital factory program, further underscoring that their strategy is proving itself out in the eyes of some of the market’s best-known names.

Tariff Strategies

Localized production to get around trade tariffs and contentious relationships is perhaps not the first thing to come to mind when it comes to advanced manufacturing processes — but neither is it foreign, nor any longer just theoretical.

I expect we’ll be seeing more cases like this popping up with great regularity. Perhaps with a bit less fanfare than when NASA “emailed a wrench” to the ISS a few years ago to prove out their own work with localized production of far-off design work, but with no less real-world (and down-to-Earth) impact.

Opportunities for 3D printing will continue to come to light in the face of ongoing trade disputes.