![[Image: Brief Mindfulness ]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/mouse-maze-and-cheese-300px1_img_5eb094c46a293.jpg)

The psychology of thinking differently can be applied to design for additive manufacturing.

DfAM is a major topic in 3D printing today, as different approaches are required to create a viable model. There are major differences between designing to add material to build up a part in additive manufacturing and designing to machine away from an initial amount of material in traditional subtractive methods. And it requires thinking differently.

Education and training are at the forefront of many initiatives to further adoption of additive manufacturing, as specific — and wholly new — skills must be learned, wherever a person is in their career.

Yesterday, I heard about a study that had been undertaken some years ago. The story was shared in a different context, as a minister looked to offer the perspective of openness as it pertains to creativity. Through his discussion of “approach brain” versus “avoidant brain” I saw some important parallels with the conversation of thinking differently in 3D printing.

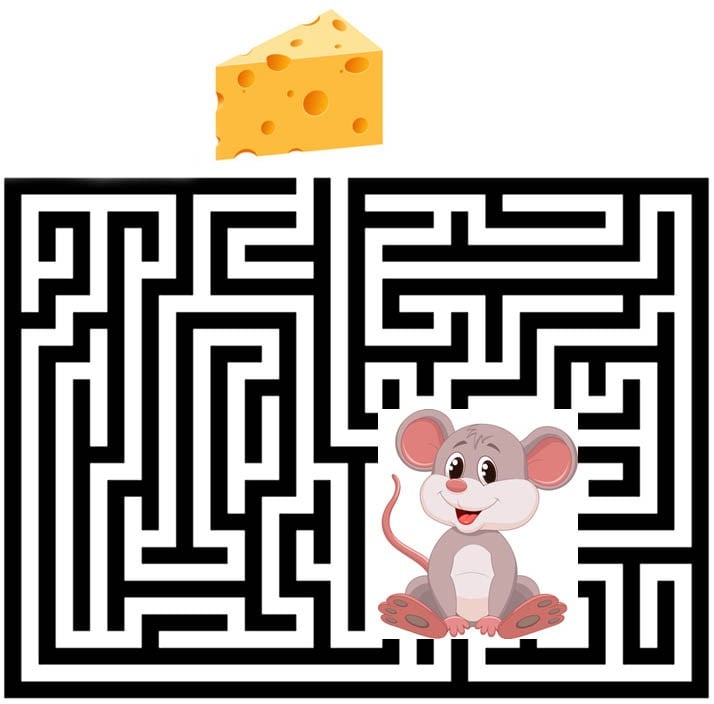

In “The Effects of Promotion and Prevention Cues on Creativity” (pdf), the 2001 study, the researchers set participants to the task of a pencil-and-paper maze in which a mouse would meet either a block of cheese (reward) or a predatory owl (risk) upon completion. After completing the maze, they worked on a series of questionnaires unrelated to that activity that gauge different ways of thinking. Those who had worked on the cheese maze were found to think more ‘outside the box’ than their counterparts who had worked to avoid putting their mice in danger.

Because 3D printing is such a new technology, relative to manufacturing, training is an evolving aspect.

How and when do you train the workforce on next-generation technology? An obvious starting point is with the next generation itself, and educational initiatives are picking up around the world starting with the youngest students and moving through higher education with advanced degrees specific to additive manufacturing.

But what about the existing workforce? How and when do they learn? Some people have even asked if they can learn; training an engineer with 30 years’ experience to make a part they’ve always made but to do it in a new way with different software, a different technology, perhaps a different material or material formulation, and with different post-processing/finishing needs is quite an undertaking. Sometimes this can lead to the question ‘Why fix what’s not broken?’ The parts have been successfully made and used for decades; why do it another way?

That’s risk-averse/avoidant thinking, and it can stymie the creative process.

The benefits of 3D printing in a manufacturing environment are many, as the suite of technologies continue to develop and meet production needs.

Think of these benefits as the cheese at the end of the maze: each corner turned is a step toward reaching those goals of viability. Training may indeed take some time and feel a bit like a maze, but thinking of the why at the end of it can keep things on track.

Worrying about the owl at the end of the maze can instead hold back the overall process. Yes, there’s a maze to get through. And yes, I’ve heard more than a few people laugh as they spit out the blanket statement that “engineers are a risk-averse group”. But when all you’re focused on is failure points, that’s where all the focus goes.

It’s important to pay attention to what could go wrong — but it helps if doing so with an eye toward what could go right, and why you’ve entered the maze in the first place.

No one seems to offer collaborative 3D printing modes on dual extrusion devices. We explain why this is the case.