![A 3D printed snowshoe [Source: MIchigan Tech]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0994a090ce.jpg)

Engineers from Michigan Technological University and re:3D propose funding makerspaces and FabLabs through 3D printing of commercial objects, but I have some serious concerns about the concept’s viability.

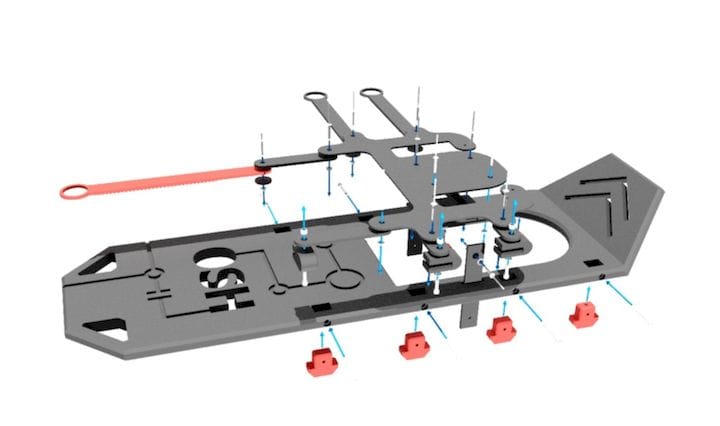

They’ve published a paper proposing a concept that uses a Gigabot X to 3D print sporting goods such as kayak paddles, snowshoes and skateboards to raise money through product sales, and at the same time help the environment by using only recycled materials.

![The Gigabot X pellet 3D printer [Source: MIchigan Tech]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0994a6acc7.jpg)

The Gigabot X is a large-format extrusion-based 3D printer that uses inexpensive industrial thermoplastic pellets rather than US$20+/kg spools of precision-made filament. This dramatically reduces the cost per print, and enables faster 3D printing. The Gigabot X was introduced to the public in 2018 by means of a Kickstarter campaign by originator re:3D.

The paper lists a number of technical calculations in an attempt to show that if a FabLab were to obtain the US$17,500 Gigabot X (and US$4,500 extruder), and operate it for fifteen years, and were operating as a “skateboard deck manufacturer” for eight hours each day, a “$2.9m profit” could be realized.

![Some of the financial calculations performed by the Michigan Tech researchers [Source: MIchigan Tech]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0994ab32a3.jpg)

I’m not quite sure where to start, as this proposal is missing so many aspects of the situation.

As a founder of a major FabLab, I can say that in practice, this concept would be a non-starter in almost every FabLab I am aware of, especially if a FabLab actually attempted to do this.

FabLabs are NOT manufacturing centers. They are prototyping centers, with people experimenting with unusual new designs. The users of a FabLab don’t need a continuous flow of objects, as suggested in the paper.

Perhaps there are outside parties who wish to request such production and pay the FabLab? If that were the case, the FabLab members who would otherwise operate the service would eventually just do it themselves if it were so profitable, leaving the FabLab without customers.

And where is this production demand coming from? I don’t see a line of requestors outside my FabLab demanding years of production of paddles, shoes or anything else. If such production were actually required, then someone from the FabLab would have to begin a serious marketing campaign and sales process to somehow round up the demand and bring it to the machine. The cost of doing that is substantial and not analyzed by the paper.

They also suggest that the maintenance required for the Gigabot X would be around US$500 per year, which in my experience is far too low. Perhaps some replacement parts could be obtained for that price but to install them you really need a paid technician to do so. Some FabLabs and makerspaces survive by members randomly volunteering their expertise, but in my experience that is not sustainable over a year or two, let alone fifteen. It’s highly likely 3D printing technology will change utterly in five years, let alone fifteen.

Another factor involved here is the product-worthiness. The skateboard print, for example, is actually a 3D printed board plus other mechanical elements, such as bearings and wheels. Where do they come from? Who buys them? How much do you pay them to do that? Who assembles the units? Who tests them according to the quality standards required? Who makes the quality standards? Who reviews the legal requirements to ensure you are not sued when the 3D printed board breaks? How much does that legal work cost?

And so on. I’m afraid this is a classic case of a technical analysis approach being applied to a business problem, where many highly-relevant, real-world factors are ignored. In most cases, the “technical solution” is vastly simpler than the rest of the business problem, and engineers are not trained to evaluate such things. If you don’t agree with this, then I point you towards the countless 3D printing startups who launched via Kickstarter and crashed miserably when they could not figure out how to properly manufacture devices at scale.

While I greatly admire the work done by these engineers and their hope to reduce costs and help the environment, I don’t think this approach will work.

Via Michigan Tech

A research thesis details the incredibly complex world of volumetric 3D printing. We review the highlights.