![Josh at work [Image: Fortify]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Josh1a_img_5eb09ac6e379d.jpg)

We caught up with Fortify CEO Josh Martin for a chat about high-strength composite-based 3D printing.

Martin’s background is in the traditional composites space, which has informed his approach to the next steps for composites technologies. Composite materials often see use in industries like aerospace, where complex, strong, lightweight structures are common.

However, Martin pointed out, these structures are traditionally difficult to manufacture, requiring “very expensive bulk materials that have to be machined”; so he “started looking to direct 3D or direct manufacturing of high-performance materials.”

Along with Dr. Randy Erb, Martin researched processes while at Northeastern University that would lead to Fortify’s Fluxprint technology. Fluxprint brings together DLP 3D printing with magnetics, creating the company’s Digital Composite Manufacturing (DCM) platform.

“Essentially what we’re doing is the highest-resolution composite system to date,” Martin said, bringing DLP to scale. “We’re changing the way we think about materials that can be used on a DLP system, like carbon fiber-reinforced, and creating the ability to realign these for additive within a high-resolution matrix.”

Because of the expense and difficulty typically associated with traditional manufacturing of composites, the Fortify team is “very motivated to essentially democratize high-performance composite materials” to enable their wider use.

Materials, it is often said, are the future of additive manufacturing.

As the hardware and software of 3D printing advance, it’s up to materials to keep up.

“We’re operating under the thesis that pure polymers alone will not equal a step change in performance without reinforcing agents to draw from composite technology. Look at how the property space — measured by strength, elongation, and other qualities — has evolved in the 3D industry. It’s been a rather linear growth and rate of improvement,” Martin said.

“These new polymers will continue, but to get a real step change in performance, the best way, in our opinion, to do this is by using additives. These are materials you can blend with the pure polymer in a resin system. This is something that’s been done in the traditional plastics space with glass- or carbon-reinforced injection material. Look how that’s been done and how that increased additive enhances performance: it really blows away the performance of the pure polymer. There is essentially no corollary for traditional plastics today.”

For additive manufacturing to compete with traditional plastics technologies, that is, additives are needed. Reinforced and otherwise enhanced materials to get just the right blends of strength and stiffness or flexibility are increasingly coming into 3D printing — but for real progress, the advances need to be for both performance and cost competitiveness.

Fortify knows that a major challenge for additive manufacturing is reaching a price-competitive blend of performance qualities — and is working toward targeted solutions.

Intriguingly for a company so focused on material qualities, Fortify operates with an open materials platform.

Last month, Fortify announced work with DSM toward high-performance composites to 3D print structural parts.

“[DSM is] not only an expert in the space, but has had its hand in the additive industry for many years. Interest is starting to perk up,” Martin said of the collaboration. “We are inviting companies such as DSM to develop resins on our platform.”

Working with partners to innovate on materials allows for what he’s called a ‘cross-pollination of ideas’ to leverage both parties’ strengths and areas of expertise. Working with unique suites of chemistries can provide that step change in mechanical properties that Martin and the Foritfy team are looking to achieve.

“We talk to a lot of industries, automotive, aerospace, and other verticals, that are looking for that next evolution within the additive space,” Martin continued.

There will be more partners to come, though none are ready yet to be announced. When I asked about these, Martin simply mentioned that “there are a few trade shows coming up.”

Another area where we can’t currently get much detail yet is on specific parts or who they’ve been made for. But, broadly, automotive will be a large focus for Fluxprint technology.

“Overarchingly, under-the-hood thermal mechanical parts, that need to hold high values in strength and stiffness, being close to engine components or general under-the-hood parts that would be exposed to temperatures of 160C, are unique for Fortify solutions to add value to,” Martin said. “One of the things we can improve is heat deflection temperature, at which the part will begin to soften or slump and lose its mechanical integrity.”

He noted that looking under the hood of any car will reveal “dozens upon dozens of polymeric parts from brackets to intake manifolds and exchangers” — and these are “areas where we have a unique advantage.” The complex geometries in parts, especially those with electrical connectors, lend themselves well to manufacture via 3D printing — and all the more so when that 3D printing can be done in materials that hold up to those demanding conditions.

“You need a part that’s going to be structural for 10 years to take on different types of atmospheric conditions, high temperatures, and exposure to oil and gas vapors. That’s something we’re very excited to work on,” Martin said.

Another major area for both automotive in general and Fortify in particular is tooling, which Fortify has identified as a beachhead market.

Operating under extreme temperatures while maintaining dimensional accuracy creates a high technical energy barrier for injection molding. Tooling, jigs, and fixtures that don’t require significant post-processing (e.g., EDM machines) and offer comparable quality to CNC milling are the initial market for Fortify.

More applications are, of course, underway as well.

“We’re in the process of looking at the hearing aid industry,” Martin said, naming one of the largest uses of 3D printing for end-use parts today. “Most shells for in-ear solutions are 3D printed…we’re working with a large company in that space to explore materials in that industry.”

He noted that we should also “keep an eye on aerospace and automotive under-the-hood applications.”

“A few other industries we have our eyes on where we’re working with partners for that will be more toward end-use part production, for tens if not hundreds of thousands of parts per year. We’ll continue to build out our suite in that space,” he said.

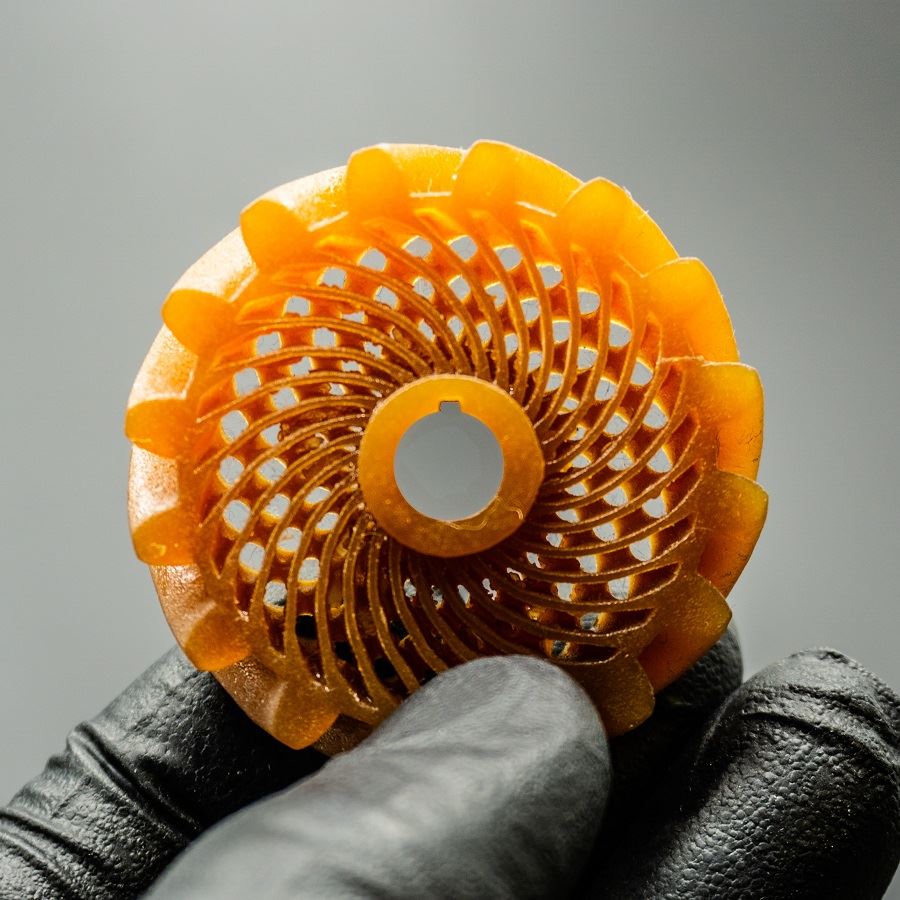

[Above: Josh Martin; a Fluxprint-made part / Images: Fortify]

With end-use part production a major focus for the 3D printing industry in general, the team at Fortify has been keeping their fingers on the pulse of the latest happenings.

“It’s definitely happening now, essentially taking on one application at a time, as these transitions usually do. I wouldn’t say as a blanket statement that you can take a solution that’s cut and molded and find an appropriate 3D printed solution that will be cost-competitive, but it definitely comes down to each individual application. Most applications will find something that can compete, and we’re finding that end-use that competes at scale has potential,” Martin said.

A humbling experience for the enthusiasm of 3D printing is remembering this technology’s place in big-picture manufacturing, and Martin found that at IMTS a few months ago.

“It really makes it apparent how mature the traditional manufacturing space is and how high the bar is,” he said. “Now we’re seeing solutions brought to the table that can be viewed through the same lens as industrial tools. It’s a real waking up moment, I would say, for the industry. Perhaps the reality lies somewhere in between what you see at IMTS and at formnext right now.”

Working toward that new reality is both humbling and exciting as 3D printing continues to advance in viability.

“One of the things we’re most excited about is opening up the property space by leveraging some of the most advanced engineering that exists today, and opening our platform to engineered additives that can change the properties of a material, whether electrical, thermal, or chemical,” Martin said. This work is “opening industries to use of our composite platform.”

Via Fortify

Elizabeth C. Engele (Lizzy) is a designer for social good, and a founder of MakerGirl.