![Sample 3D prints using a self-healing elastomer [Source: Nature]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/healing-ov_result_img_5eb09cdd4b61e.jpg)

The dream of self-healing materials is slowly becoming a reality.

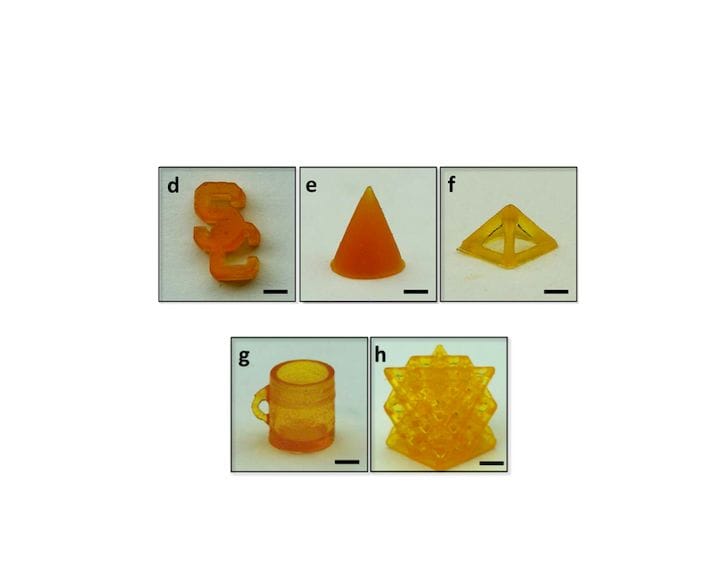

Researchers at USC’s Viterbi School of Engineering have been examining the notion of creating polymers that can actually heal themselves. That is to say, when they are cut, they can be re-joined together without incident.

How could this possibly work? The answer is in the chemistry.

The researchers used a photopolymerization process with a special resin mix. Their mix contained a specific ration of thiols and sulfides. Why so? They explain how it works:

“The paradigm relies on a molecularly designed photoelastomer ink with both thiol and disulfide groups, where the former facilitates a thiol-ene photopolymerization during the additive manufacturing process and the latter enables a disulfide metathesis reaction during the self-healing process. We find that the competition between the thiol and disulfide groups governs the photocuring rate and self-healing efficiency of the photoelastomer.”

And:

”The strategy relies on a molecularly designed photoelastomer ink with both thiol and disulfide groups, where the former facilitates a thiol-ene photopolymerization during the AM process and the latter enables a disulfide metathesis reaction during the self-healing process. Using projection microstereolithography systems, we demonstrate the rapid AM of single- and multimaterial elastomer structures in various 3D complex geometries within a short time (e.g., 0.6 mm × 15 mm × 15 mm/min = 13.5 mm3/min). These structures can rapidly heal the fractures and restore their initial structural integrity and mechanical strengths to 100%.”

![The self healing chemistry [Source: Nature]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/healing-process2_result_img_5eb09cddaa767.jpg)

In other words, one substance promoted polymerization, and the other promoted healing. But they interfere with each other so an optimum ratio had to be determined.

![A self-healing elastomer example [Source: Nature]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb09cde074d8.jpg)

The healing process does not occur automatically. It was discovered that an application of 60C heat for a short time period and a small force would be required for the material to fully re-join together.

Their testing was quite dramatic:

“The 3D actuator was first designed and additively manufactured. A 10 g weight was hanged at the bottom of the actuator that was connected to a syringe pump. When the syringe pump was moved, the weight was lifted up. A camera was used to image the distance change of the weight. Then, we cut the actuator in half with a blade and contacted back to heal for 2 h at 60 °C. Once healed, the actuator was used to lift the 10 g weight again for multiple cycles.”

They repeated this test in a variety of experimental setups, verifying that one could do this process with composite materials, and even conductive electrical prints.

The power here is that they are using a resin process, where you can easily add almost any kind of additional material to the resin to change the properties of the final object. Resin wins!

Obviously, this is merely research at this point, but it seems quite promising and could likely be commercialized. I can see many different applications for such a material, should it have other appropriate engineering properties. Imagine shoes that heal themselves when ripped, or tires that heal themselves with a heat gun.

It’s not clear whether you need to 3D print this material to achieve the same effects, but if not, then the application of the self-repairing elastomer would be quite widespread.

I’ve always thought materials will be the key to the future of 3D printing, and this is certainly one excellent example of that.

Via Nature

A research thesis details the incredibly complex world of volumetric 3D printing. We review the highlights.