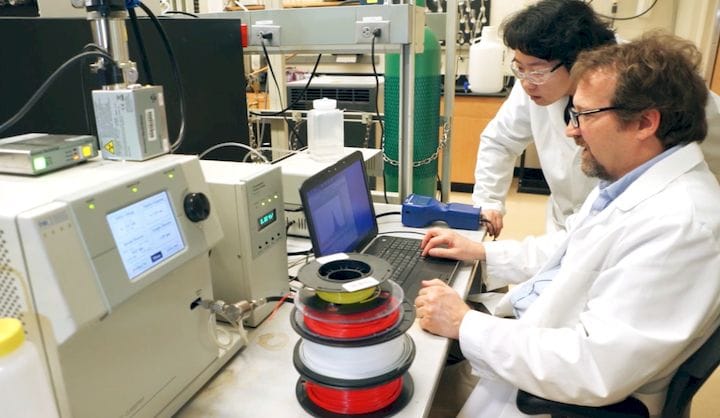

![Researchers investigating 3D printer particle emissions [Source: Vimeo]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a12779ecc.jpg)

It’s been known for several years that desktop 3D printers, and presumably any extrusion 3D printer operating in an open environment, can be potentially dangerous due to the creation of ultrafine particles (UFPs) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs).

The studies thus far, however, have been fairly limited in nature.

UL Chemical Safety and Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech) have now published two of the most extensive studies on the topic to date. Focusing on desktop 3D printers, the partners found that the machines produce UFPs during operation that can be inhaled and brought deep into the pulmonary system. They also found over 200 VOCs, including irritants and carcinogens.

Naturally, this information could affect how and where a 3D printer is used, what sort of materials might be printed with and how suitable this technology might be in a classroom setting.

To get a better understanding of what this means and how to deal with this information, engineering.com has looked further into the research and provided some context here.

Previous Studies

3D printing journalist and professor Mark Lee has documented the history of safety research in desktop 3D printers. He pointed out that in 2007, it was discovered that 2D laser printers emit UFPs. The particulate matter was five times greater during working hours, which resulted in a public relations issue for HP, which ultimately remedied the issue.

In 2013, it was discovered by the Illinois Institute of Technology that UFPs were emitted by desktop 3D printers using filament extrusion technology. In thermal plastic processing, gases and particles are emitted, as well. Using two printers printing with the cornstarch-based polylactic acid (PLA) and three printing with acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), the team found that the amount of UFPs in a closed room increased 15 times the background rate when the machines were operating.

In 2015, researchers at Seoul National University conducted a study with two different plastic extrusion printers using PLA and ABS inside of a 1-square-meter test chamber, looking for both UFP and VOC emissions. PLA produced UFP rates that were 21 to 26 times higher than the background and some VOCs, including formaldehyde emissions 5.2 times higher than outside air concentrations.

ABS was much worse with UFP particle counts 345 greater than the background rate and various vapors, including ethylbenzene levels “16.4 times higher than outdoor air concentrations, isovaleraldehyde at 11.9 times higher, acetaldehyde at 3.2 times higher,” according to Lee.

In 2016, a new study from the Illinois Institute of Technology examined different plastic filament types and both UFPs and VOCs. ABS produced the most UFPs and VOCs, but the team notably found that “only three chemicals made up over 70 percent of all VOC emissions; namely styrene from ABS and HIPS, caprolactam from Nylon, PCTPE, Laybrick and Laywood, and lactide from PLA.”

To learn more about these previous studies, it’s worth reading Lee’s full article.

Read more at ENGINEERING.com

We were able to view video footage of the 3D printing hair-caught incident from last week and have determined exactly how it occurred, and how to prevent it from happening again.