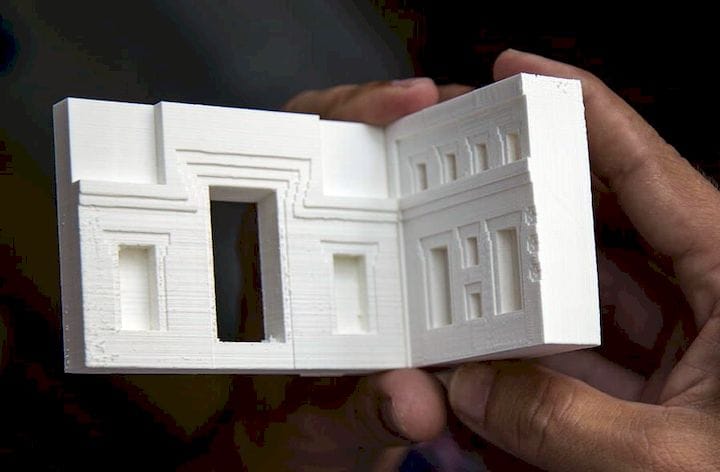

![3D print of a portion of an ancient building [Source: Heritage Science Journal]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a090d82e7.jpg)

A 3D printing technique was used to develop a 3D virtual model.

Researchers at UC Berkeley were faced with a near impossible problem: an ancient ruin was to be investigated to determine its original structure. The issue was that the site, along with being a destroyed ruin in many pieces, had been looted for centuries. Looters not only removed items, but broke stones and moved them far from their original locations.

![Not much left at the Pumapunka site, even in this 1893 photo [Source: Heritage Science Journal]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a0913866a.jpg)

The structure under investigation was the Pumapunku building, built around 500AD at the Tiwanaku site in Bolivia. The building was the inspiration for much of the architecture of the Incas, who used some of the techniques at their own mountain city of Macchu Pichu.

In spite of the earnest efforts of many scientists over past decades, no one has been able to figure out what this building actually looked like, due to the very limited information surviving.

While the scientists could accurately measure the location, orientation, dimensions and geometry of surviving pieces, there was no easy way to put the 157-stone jigsaw puzzle together. Worse, there were no useful written accounts of the structure.

The surviving pieces of the structure varied considerably in size, ranging from items you could easily pick up with your hands to massive 20t blocks several meters in size. There was clearly no way the parts could be physically matched with each other, and in fact they simply aren’t moving from their places.

Dr Alexei Vranich said:

“A major challenge here is that the majority of the stones of Pumapunku are too large to move and that field notes from previous research by others present us with complex and cumbersome data that is difficult to visualize. The intent of our project was to translate that data into something that both our hands and our minds could grasp. Printing miniature 3D models of the stones allowed us to quickly handle and refit the blocks to try and recreate the structure.”

One obvious approach might have been to simply use virtual 3D models of the stones. These could be quickly manipulated via 2D screens to see how they could fit together.

However, that process is quite unintuitive and time consuming, as using 3D virtual tools to manipulate an object is far less efficient than simply picking it up and rolling it around in your hand. The “real” 3D visual input as well as the tactile input made it far easier to develop the solution.

The pieces were 3D scanned using a photogrammetry system. This created an initial set of 157 3D models of building stones located at the site. However, many of these stones were damaged, making it more challenging to fit them together.

![Reconstructing the likely original shape from a 3D scan of a broken stone [Source: Heritage Science Journal]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a0917dc87.jpg)

The researchers examined the 3D models of the scanned blocks and found that it was possible to extrapolate the geometry of the missing elements, as seen in this image. Incredibly, they used SketchUp to do this 3D modeling; it is not a solid modeling tool and is rarely used by those developing printable 3D models.

![A raw 3D print of a broken stone from the Pumapunka site [Source: Heritage Science Journal]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a091cfec1.jpg)

The researchers 3D printed the resulting 3D models at 4% of their original size using an older Z Corp Z310 powder printer. This device can produce relatively accurate 3D prints in a sandstone-like material.

These prints were then placed on a large model of the foundation, which is more or less intact at the site. The building would have fit on top of the foundation, thus it was the obvious choice for a base during reconstruction.

![A huge 3D printed puzzle for archaeologists to put together [Source: Heritage Science Journal]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a092576b4.jpg)

It then remained the task of the researchers to fit the blocks together, which they describe in their paper as follows:

“For most people, a puzzle is a pleasant pastime; for archaeologists, manipulating small fragments of a larger object is a significant representation of what we do back in the lab. Archaeologists are trained in spatial visualization by spending long periods of trial and error, piecing together objects from bits of broken pottery, stone, and bone.

Anecdotes abound among archaeologists of quickly piecing together shattered bits of pottery or realizing that a piece of sculpted stone would fit well in another location of the site. Physical anthropologists are well known for the ability to take a near featureless eroded bone fragment and mentally rotate it to its proper location on the human skeleton.

Other professionals, such as masons who work with non-course stone or irregular blocks, also develop an uncanny ability to recall the location of the perfect stone among a disorganized pile in order to fill an odd-shaped chink in a wall. Though the actual mental process of insight is not fully understood and beyond the scope of this research, we do know that it can be cultivated both through training and by creating proper setting.”

In other words, it was really hard to do this.

But they did! The researchers were able to eventually use the 3D printed pieces to reconstruct most of the Pumapunka building, although many small details will remain obscured in history. However, using their puzzle solution, the researchers were able to then create a full 3D visualization of the structure.

![3D visualization of the Pumapunka building after using 3D printing techniques to reimagine its original form [Source: Heritage Science Journal]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a092ab1b2.jpg)

I’m fascinated with this approach, as it demonstrates a clear application of 3D printing that has a significant advantage over other digital approaches.

While this is of great use to archaeologists, I’m wondering if there are other applications. Forensic police work, perhaps?

MakerBot’s new Classroom product is set to shake up the education market for 3D printing significantly due to its features, price and most importantly, how it was designed and implemented.