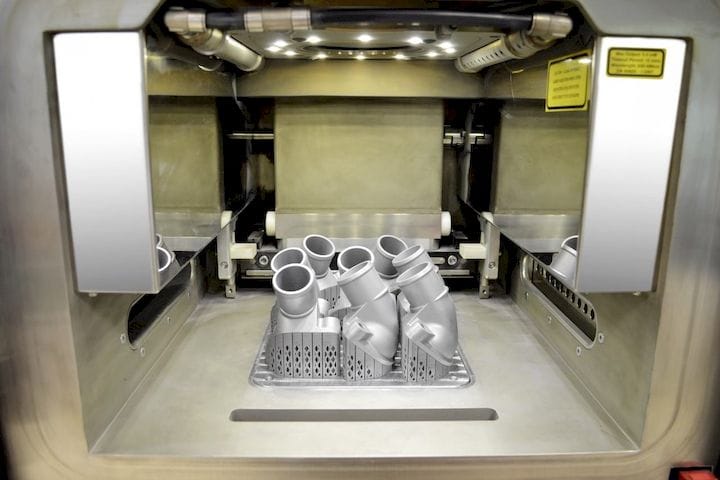

![Some 3D printed spare parts [Source: Mercedes Benz]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a4e33bad2.jpg)

3D printing enables many new business models, one of which is on-demand spare parts.

The concept is quite powerful because traditional spare parts processes are incredibly expensive. Consider the workflow and resources required to implement a spare parts inventory:

-

Mass production lines are set up once at great expense to manufacture the original salable products

-

The expensive production line is let to run for some time after production completes to produce many usable spare parts, identical to those used in products

-

These parts are stored in warehouses for long-term use

-

Parts are drawn from storage on demand, but require shipping, sometimes for very long distances

-

If spare parts inventory runs out, then support is usually dropped due to the expense of setting up the manufacturing line once again

If you think this sequence sounds troublesome, you’d be right. It’s expensive, particularly the storage requirement. If the parts are bulky, you might require very large warehouses, and they’d have to be staffed, managed and tracked. It’s all very pricey.

Looking forward, there are new possibilities with 3D printing, particularly with the advent of many new production-quality material capabilities. This means that in theory, a 3D printer might be able to produce a part similar or identical to original parts. The “inventory” becomes the library of 3D models instead of a warehouse full of aging parts. It’s all very digital.

If that’s the case, then you might think there would be a rush towards this business model by companies desperately seeking to reduce their inventory costs.

There are even at least two companies specializing (Kazzata and Spare Parts 3D) in this process so that clients would not have to worry about the process; they merely provide the 3D models to the outsourcer who then handles requests for spare parts on their behalf.

Some of the larger 3D printing companies, most notably being Stratasys, have been exploring the idea of digital inventory with large transportation companies who, up to now, have been required to store massive vehicle parts for literally decades.

This should be a no-brainer, should it not? Companies should switch to on-demand spare parts.

That has clearly not happened, at least not yet. Why could that be? There must exist barriers to adoption that are preventing progress. Here are some ideas of what they might be:

Fear: I am quite certain that many companies do not trust 3D printing to be able to achieve this concept. Imagine a factor owner making the fateful decision to shut down the production line early and NOT make the usual quantity of spare parts because they trust that some 3D printing technology would be able to serve their needs for perhaps decades into the future? Or even more riskier, a small startup providing a spare parts service? No thank you, we’ll make the parts ourselves. I think this will be the biggest barrier to adoption.

Materials: Currently 3D printers offer the ability to produce parts in only a limited set of possible materials. If those possible materials don’t include the specific material required for the spare part, there’s no point in attempting to print it, as it is critical to have identical engineering performance for legal reasons.

Quality: Even if the material is in fact available, the part’s quality must match, or at least be very close to that of the original part. Meanwhile, 3D printers current offer relatively poor surface quality as compared to original injection molded parts. For some applications the surface quality will be critical and thus this approach cannot be used.

Intellectual Property: If a third party service is producing the 3D printed spare parts, then it would be a requirement for the 3D models associated with the spare parts to be transferred to the control of the outsourcer. What if they are compromised? What if the provider goes out of business and its assets are auctioned off to whomever? Does the third party have the necessary certifications and processes to handle the sometimes critical digital 3D models, for, say, a military application? All of these could prevent consideration of 3D printed spare parts.

Value: Mass production lines are expensive to set up, but once done can produce many parts at very low cost. Thus the manufacture of many spares can often be done for very low cost. If the manufacturer sells those spare parts at premium prices to desperate customers, then there is great profit involved. In fact, it’s almost guaranteed if they get the quantities correct: Every spare made could have a 20X margin associated with it. The same cannot be said for 3D printed parts. In other words, there is a known profit associated with traditional spare parts approaches, and an unknown profit with 3D printed approaches.

All of these reasons could cause a company to reject the notion of 3D printed spare parts on demand, perhaps why the take up is relatively slow at this point. It’s possible some of these reasons may eventually evaporate, but not for a while.

Meanwhile, there is one case where 3D printed spare parts do in fact make instantaneous business sense: That is when the original parts are ALSO 3D printed – on the same equipment. This is the approach that is being pursued by Stratasys, and will no doubt be the first practical and large-scale implementation.

No one seems to offer collaborative 3D printing modes on dual extrusion devices. We explain why this is the case.