![3D printed metallic glass samples, using a filament extrusion process [Source: ScienceDirect]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a7cd3c962.jpg)

A research paper discusses methods of 3D printing metallic glass, and their findings are quite startling.

They’re attempting to solve the current problems in 3D metal printing. When contrasted with thermoplastic 3D printing, we find that the filament extrusion process is able to easily produce arbitrary geometries without issue. However, thermoplastic 3D prints are far less strong than metal parts, significantly limiting their use in production applications.

Meanwhile, metal 3D printing currently is challenging due to the extreme costs involved that are a result of the powder processes employed by today’s equipment. This prevents widespread use by any but the few industries willing to accept high part prices.

Some advanced filament extrusion systems have been adapted to 3D print “metal”, but really they are simply 3D printing a binder that happens to contain metal powder. The resulting “green” prints must be treated with solvent to remove the binder, and then the remaining metal object must be sintered in a furnace to complete the metal part. This is a less expensive process, but involves multiple steps and does not always result in a properly strong metal part.

![Strength chart showing where metallic glass materials fit [Source: ScienceDirect]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a7cda52f7.jpg)

Pure metals cannot be 3D printed using the filament extrusion process as they typically do not have a temperature where the material is sufficiently viscous to enable pushing it through a nozzle. It’s usually solid, then suddenly liquid. That won’t work.

However, the researchers noted that certain bulk metallic glass materials DO offer an appropriate viscosity within reasonable temperature ranges.

They wondered whether this characteristic could be leveraged into a form of metal 3D printing using filament extrusion. So they set about doing so by experiment.

Their first step was to create an appropriate “filament” using the bulk metallic glass. They chose Zr44Ti11Cu10Ni10Be25, apparently a commonly available bulk metallic glass material that has optimum viscosity characteristics. Using a casting process to ensure maximum viability, they produced “cores” of this material 700mm in length. While this isn’t exactly a “filament”, such cores could be mechanically delivered to an extruder easily using slightly different approaches.

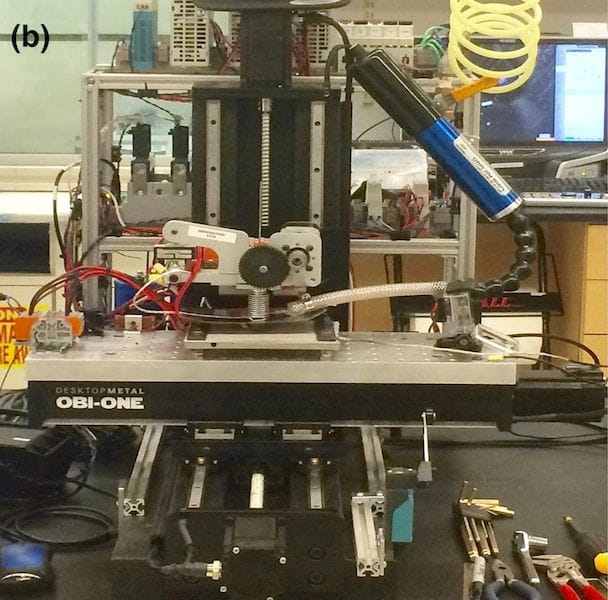

They then designed a 3D printer to execute this process, which from all appearances seems to be rather like a typical desktop filament extrusion model.

One important required feature they discovered is that to ensure layer bonding during extrusion, the base layer must be heated to approximately the same temperature as the fresh extrusion. This is to enable the materials to deform and thus displace any oxidation that would prevent proper bonding between layers.

![The unusual heating system of the experimental 3D metallic glass printer [Source: ScienceDirect]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a7ce44681.jpg)

How do they heat the base layer? They use a resistive heating solution, in which electricity is routed through the base plate and print. This is an approach very similar to how Essentium heats thermoplastic material, except that the researchers were using pure metallic glass material. They’re extruding this material at 450C, which is pretty hot for a desktop 3D printer.

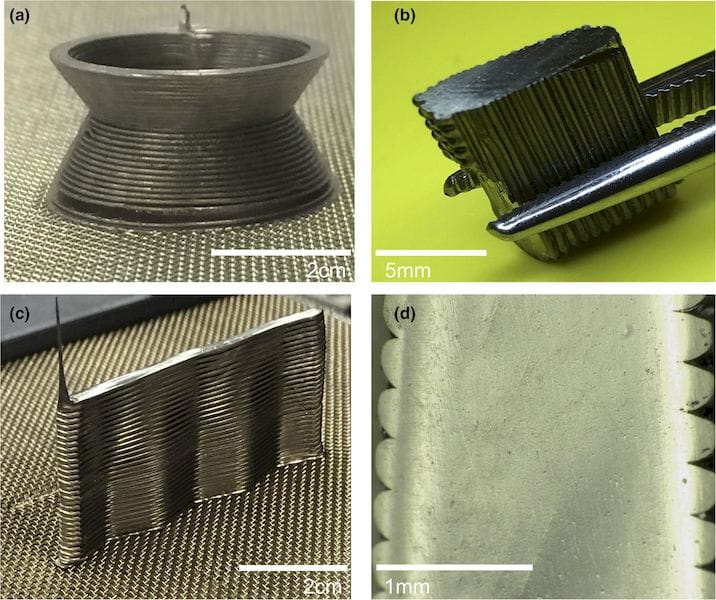

Once set up, the researchers were able to successfully 3D print a variety of different geometries quite successfully. Their testing revealed very significant strength in the prints, although not quite as much as the native material itself. But far beyond anything you’d get from thermoplastic material.

It seems that they have successfully devised an entirely new 3D printing process that can deliver metal parts.

But there’s a massive implication here: their process works WITHOUT requiring any specialized environments that are mandatory when 3D printing in metal powder, which can oxidize, humidify, poison or even explode in air. This suggests 3D printers devised using this process could be very substantially less expensive than most current metal 3D printing equipment.

However, there is a catch: it works only with bulk metallic glass materials, and even then only those that offer appropriate viscosity ranges. You can’t simply ask for a “titanium” print with this method like you can with powder approaches, where you can 3D print almost any metal material.

![Jan Schroers is an advisor to Desktop Metal [Source: Desktop Metal]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a7ce99b99.jpg)

One more thing: there seems to be a significant link between this research at Desktop Metal, one of the companies currently marketing advanced less expensive metal 3D printing systems.

The lead researcher on this paper is Jan Schroers, who just happens to be both Advisor to Desktop Metal and also Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science at Yale University. In fact, further investigation shows MANY of the authors of this research are in fact affiliated with Desktop Metal in very significant ways, including:

- Ric Fulop, Co-Founder and CEO, Desktop Metal

- Jonah S. Myerberg, Co-Founder and CTO, Desktop Metal

- Emanuel M. Sachs, Co-Founder, Desktop Metal

- Yet-Ming Chiang, Co-Founder, Desktop Metal

- Christopher A. Schuh, Co-Founder, Desktop Metal

- Matthew D. Verminski, VP of Engineering, Desktop Metal

- A. John Hart, Co-Founder, Desktop Metal

- Michael A.Gibson, Materials Scientist, Desktop Metal

- Nicholas Mykulowycz, Process Team Manager, Desktop Metal

- Joseph Shim, Hardware Engineer, Desktop Metal

- Richard Fontana, Principal Engineer Hardware, Desktop Metal

- Peter Schmitt, Chief Designer, Desktop Metal

- Andrew Roberts, Senior Software Engineer, Desktop Metal

Additional affiliations include MIT, Yale, and the University of Massachusetts.

And there’s more.

![Who made the Obi-One 3D metallic glass printer? [Source; ScienceDirect]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/image-asset_img_5eb0a7cee596b.jpg)

If you look closely at the image of the experimental printer above you will see the words “Desktop Metal” emblazoned upon it.

So it would appear that Desktop Metal is taking extreme interest in this particular project.

Hmm.

“3D printing metals like thermoplastics: Fused filament fabrication of metallic glasses” was published in the September 2018 issue of Materials Today.

Via ScienceDirect

Aerosint and Aconity have proven out their work in multi-metal powder deposition 3D printing.