We were directed to a patent describing a composition for 3D printable concrete.

This would certainly be a very useful capability, as the many attempts at 3D printed buildings using concrete extruders have had mixed success. However, most, if not all, of them have been using standard concrete materials.

We know from experience with thermoplastic 3D printers that use of “off the shelf materials” is not always optimum. Early desktop 3D printers, for example, tended to use ABS material simply because it was available everywhere in the form of “welding wire”.

This material was usable in early desktop 3D printers, but just barely. It suffered from severe warping when printing on cool surfaces – and those were the only kind of surfaces available in those days, and smelled awful when printing.

Years later after the machines became widespread, suppliers began to come forward with purpose-designed 3D printing materials that actually met most of the needs of users. Materials that didn’t warp, offered higher temperature or chemical resistance, were far safer and other characteristics suddenly emerged.

I don’t think that phenomenon has yet happened in 3D printed concrete.

Or maybe so with US Patent 20180057405, published in March of this year.

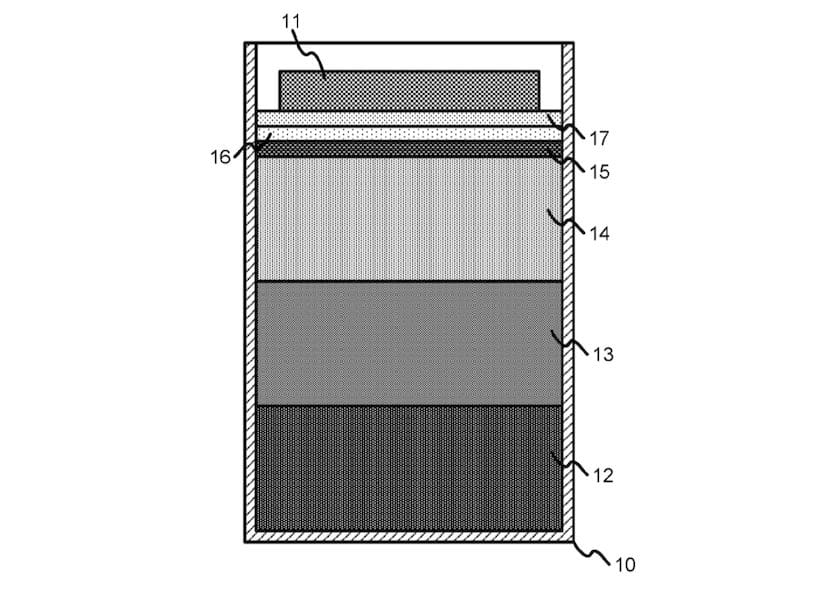

The gist of the patent is that they’ve developed a way to produce true concrete, which is a mix of cement and a rocky aggregate material, from which most of the strength is obtained.

Most previous attempts at 3D printed concrete were really mostly cement because the rocky aggregate present in concrete would tend to jam in extruder nozzles unless they were of large size. This formed a kind of barrier to the types of applications possible.

But the new method apparently gets around this problem through the use of a precise mix of materials. The abstract:

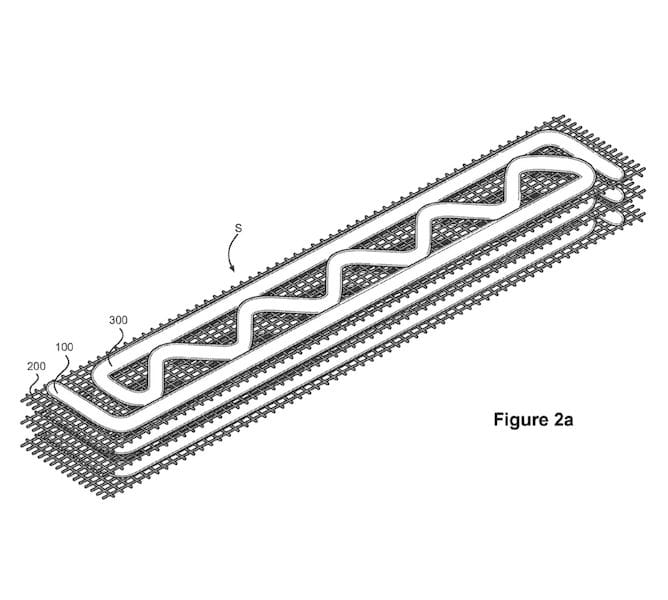

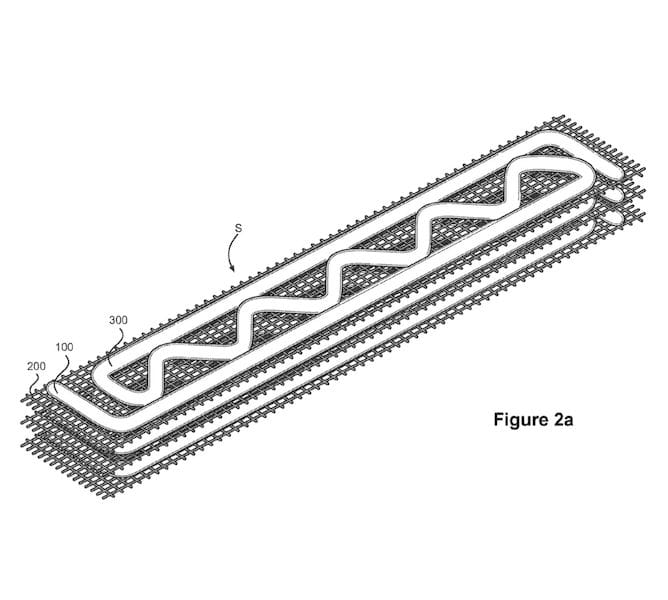

A printable concrete composition is made from the combination fo a solid mix, water and various liquid admixtures. The solid mix includes quantities of aggregate, coarse sand, and fine sand in an approximately 1:1:1 critical aggregate ratio, as well as a binding agent present in a critical binding ratio. Solid admixtures include clay, fly ash, and silica fume. This solid mix may be prepackaged for later combination with water and liquid admixtures. The solid mix compbines with water at a critical water ratio ranging from approximately 0.44 to approximately 0.50. Liquid admixtures include flow control, plasticizer, and shrinkage-reducing admixtures. Once the printable concrete composition is prepared, a user may print a structure without further modification of the composition. Users may embed mesh between layers of the printable concrete composition to reinforce or stabilize the structure.

This sounds quite intriguing, as they seem to have considered several aspects of 3D printing that may not be handled by current concrete mixes, such as shrinkage.

But wait, who are “they” in this case?

On the patent the applicant is listed as “United States of America as Represented by The Secretary of The Army”.

Yes, this 3D printable concrete mix has been patented by the US Army.

For sure, the US Army would clearly build many concrete structures, and one can imagine them 3D printing such buildings in remote areas on demand in some future world. But why do they need to patent it?

Would not their work, at public expense, be made freely available to the public? Surely this could be a huge positive in the world of concrete printing. And it’s clearly not some kind of secret black project, as it has been publicly patented.

It may be that the US Army is patenting it so that no one else can do so – and subsequently charge them for use of it. A pre-emptive patent, perhaps?

But for me the importance of this development is that it appears moves are being taken towards developing more feasible 3D print materials for large structures. That’s a very good thing because the world of desktop 3D printing – in the engineering space – took off about the same time as the blossoming of materials.

Maybe the same thing will happen to 3D printed buildings?

Via Patent Yogi