3D printing offers tremendous advantages, but we don’t mention them as often as we should.

Those unfamiliar with 3D printing tend to see it as either just another manufacturing tool little different from others, or as some kind of magic replicator that can do things it really cannot. The truth is somewhere in-between: 3D printing can do some functions that are not quite magic but might appear so to some, and there are plenty of things it cannot do, or cannot do effectively, particularly in the financial sense.

One common 3D printing practice we like to write about is how inventive folks devise radically new versions of a current part. Usually it’s made with lower weight with a complex geometry that saves material where it isn’t needed.

There’s even 3D software tools that can automatically generate these highly unusual 3D models without a lot of human intervention. Models tend to be of a shape humans might not have conceived of, yet they are of optimum design.

But there is another very common practice with 3D printing, and it’s so common we hardly ever write about it on this publication. Just in case you don’t know, we’ll describe it here.

The practice is to simplify the process of prototyping. In conventional practice a design is sent to a custom manufacturer where a prototype is expensively made using a combination of making equipment, such as CNC mills, injection molding or others. The result is sent back to the requestor for testing.

The problem with this process is that it often takes too long and is expensive. Thus the number of prototypes was usually kept to a minimum unless there was some compelling reason (and unlimited budget) to do so. Thus designs were often less than optimum because the number of prototype attempts were low.

This scenario changed with the introduction of easy 3D printing, where one making device could produce a broad range of geometries, far wider than most traditional equipment could handle. Yes, the results were not perfect as the parts might have poor quality surfaces and made from the wrong material, but for prototypes that could be sufficient.

The change meant that designers could far more easily attempt multiple prototypes in efforts to refine their design. And in some cases it even allowed parties to do prototyping at all, since the cost of prototyping might have previously been beyond their reach.

One terrific example of this approach was recently published by Sinterit, the Poland-based producer of high resolution nylon powder 3D printers.

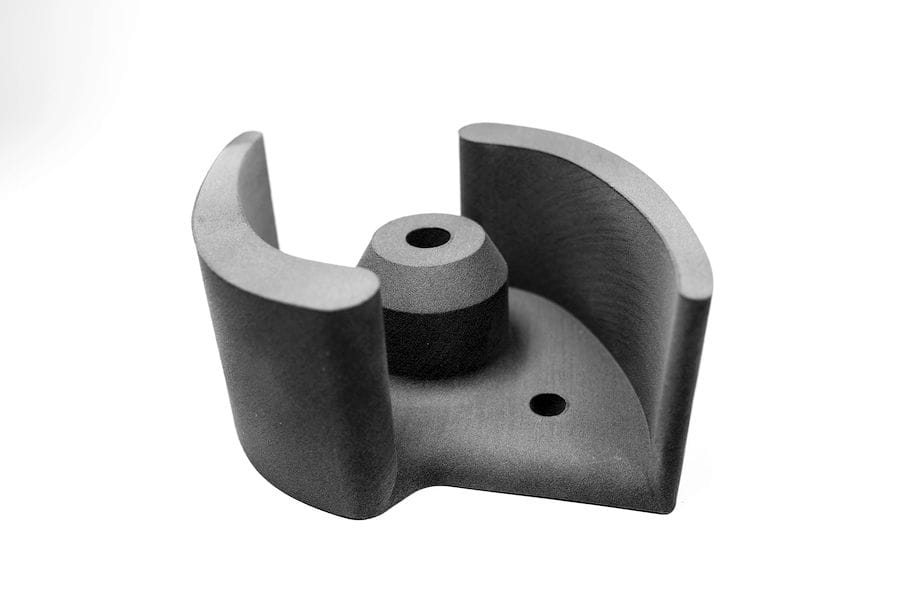

They described an emergency situation that recently happened in California, where wildfires threatened Los Padres National Forest. Firefighters involved make heavy use of powerful water pumps to deliver as much extinguishing water as possible to the fire, and this must be done as fast as possible. Thus it’s critically important for the water pump to be optimally designed, able to push the most possible water.

Those involved used a Sinterit 3D printer to produce prototypes that significantly optimized their development process. In this case they performed eight iterations of prototypes, each successively better than the last.

But the real benefit was in the making of each prototype. Sinterit reports that their previous traditional approach involved eight different activities to prepare the prototype, while the new, 3D print-powered approach required only two. This reduced the time required to produce a prototype by 30%, enabling them to attempt more prototypes within the same budget.

Yes, this is a simple use case, but it is so powerful that it needs to be described, even if many 3D printer operators already perform this practice.

Some of our readers have not yet made their way into the world of 3D printing, but perhaps after learning this basic fact of the technology, they may be more interested in doing so.

Via Sinterit