Robert McNeel & Associates, makers of the popular Rhinoceros 3D CAD tool, have shipped V6, but with a very intriguing change.

“Rhino3D”, as it is known, is a NURBS-based 3D modeling tool that’s used worldwide by many in both industry and for artistic endeavors. It’s frequently used by higher-level educational institutions as the tool of choice to teach students. It’s used often to develop visual 3D assets, but can also be used for solid 3D modeling suitable for 3D printing. I’ve done so myself.

Rhino3D V6, which is currently available only on the Windows platform, incorporates a number of new features, as you would expect with an “x.0” release. In fact, McNeel has not released a major upgrade for the product in five years!

Along with countless minor fixes, many of the new features focus on visual asset improvements, such as improved material selections or visual rendering features.

But what is most intriguing to me is a key change, and in fact the very first “new” feature listed by McNeel: the default integration of Grasshopper.

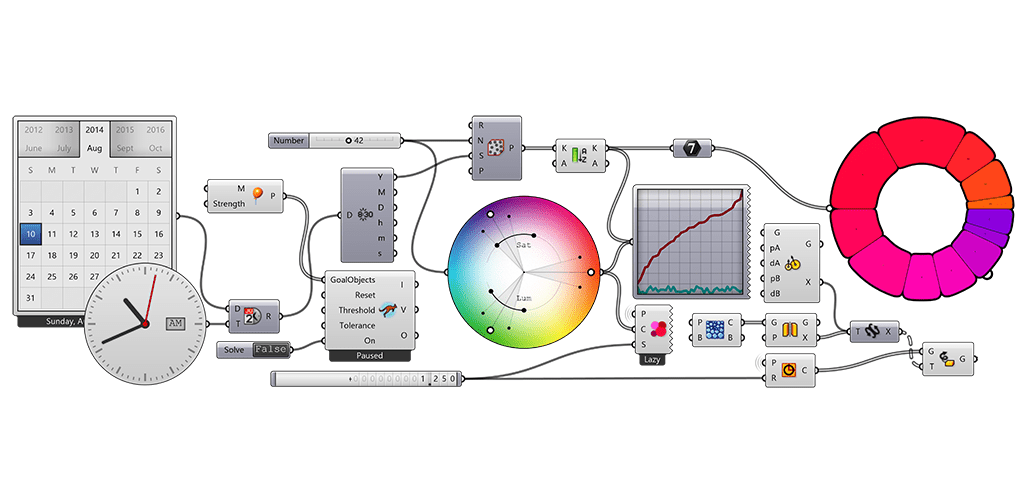

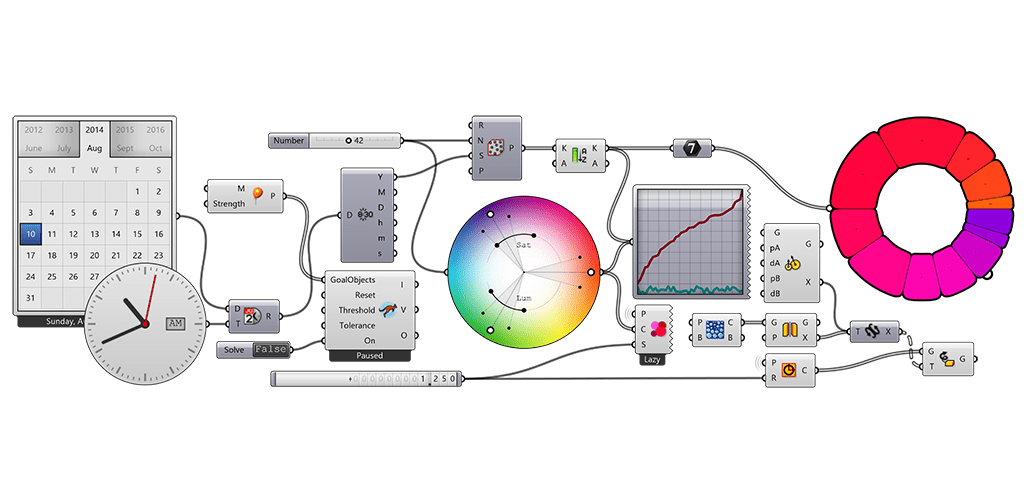

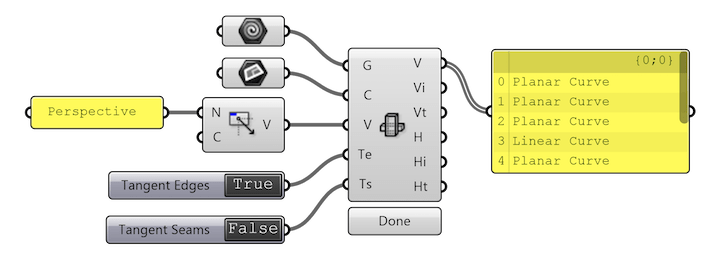

If you’re not familiar with Grasshopper, it’s (until now) been an extra plugin for Rhino3D, which boasts of a very wide variety of add ons. Grasshopper is a fascinating system which permits a designer to generate a 3D model programmatically. However, you’re not using lines of code as you might in OpenSCAD; instead you create a kind of “flowchart” whose nodes mash around points in space and apply various Rhino3D transformations.

Grasshopper has been used to create many amazing 3D prints in the past; if you see an incredibly detailed and massively complex organic 3D print, there’s a good chance Grasshopper was used to generate it.

Now, why is this so interesting?

It seems to me that the industry is now catching on to the notion that generative 3D designs are the future for 3D printing. Recently we’ve seen Desktop Metal, an equipment manufacturer, produce a generative 3D modeling system specifically to allow their prospective clients to more easily create useful – and financially feasible – 3D printed metal objects.

It’s a breathtaking vision: instead of designing the object, you simply define the requirements: mechanical, thermal, electrical, cost, weight, etc, and allow an algorithm to generate the 3D model. And generative 3D models made in this way could certainly be more effective in meeting all the requirements than any individual designer could likely do by hand. And it can often be done faster and cheaper as well.

We’ve also seen how Carbon has been using generative software to help their clients design 3D objects that they could not produce in any other ways.

Smart 3D printing companies are jumping on this train, as it seems to be the key to future growth. Historically, 3D printers have been around for decades, but have been only lightly used by industry. The reason is that almost all companies have not understood how the technology could benefit their operations. 3D printer manufacturers have spent millions attempting to “educate” industry clients.

But the problem has been that even if a company understands that it could theoretically create amazing, impossible new products with 3D printing, they don’t always have the software 3D CAD tools to do so. Thus the interest in creating and promoting such tools to industry by some 3D printer companies.

My thought is that this style of 3D modeling will eventually come to dominate future design processes. It only makes sense once you extrapolate the benefits.

Currently this is only in its very early stages, but one can see how additional features can be gradually added to the point where an entire or near complete design could be generated.

McNeel’s announcement that Rhino3D now includes Grasshopper, a generative tool, by default is a step in that very direction. It’s a small step, but I would not be surprised to see Grasshopper gradually take a much more prominent role in the Rhino3D system.

Via McNeel