I’m reading an interesting research report on Phys.org that describes a method of applying a surface finish to metal parts.

The idea is to apply a surface finish on a part that is made from a different metal than the original part. The process can also be used to repair parts by using the same material as the original part. This can potentially alter the engineering properties of the part, for example providing different strength, electrical or thermal characteristics.

This process is used in industry today, and it’s called the Cold Gas Dynamic Spray process. In this process small particles of the new material are jetting at high velocity towards the surface of the part. The high kinetic energy is transformed into heat upon impact, which softens the particle and creates a bond. After a time, you’ve applied a new surface material.

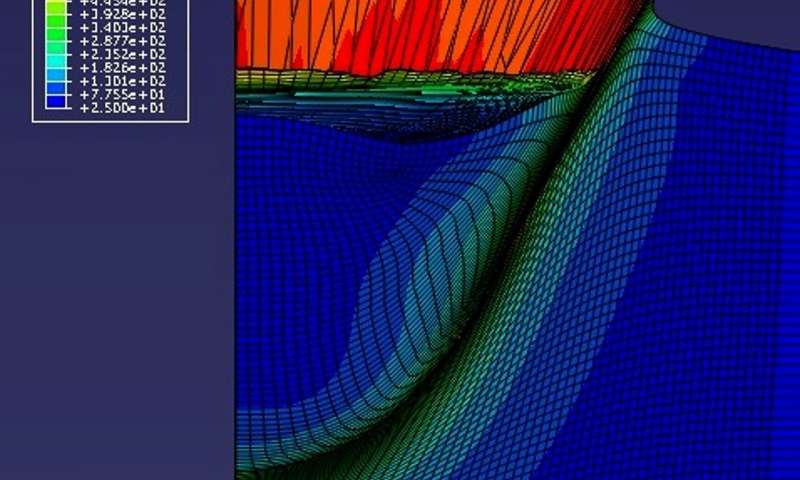

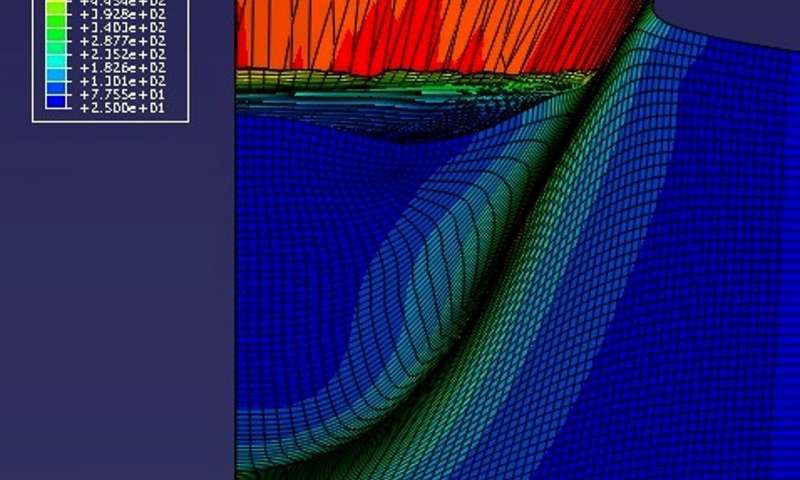

However, it seems Cold Gas Dynamic Spray is a tricky process because the particles must hit at an optimum velocity and direction to create just the right amount of heat for optimum application. New research from the University of Johannesburg proposes methods of handling this challenge by using a 3D model of the impact sequence and adjusting accordingly.

What I’m wondering is how this might be coupled with 3D printing technology. One thought is that because many 3D metal printing processes can employ only certain metal materials, it might be used as a way to coat 3D printed metal parts with alternate finishes to achieve engineering requirements.

Since virtually any metal particles can be jetted, it stands to reason that there would be few limitations of materials for this approach.

One company, Spee3D, uses something similar to this: their “supersonic” concept actually builds entire metal parts from scratch in this way. And their process holds the same advantages as above: more materials are possible.

But could the other 3D metal printer manufacturers “catch up” by employing a Cold Gas Dynamic Spray post processing step? If so they could then produce parts that are available in far more materials than ever, at least on their surface? For many applications this might be sufficient.

Another possibility is to build in Cold Gas Dynamic Spray tooling right into the 3D printer itself, creating a kind of hybrid machine that can produce such parts directly. Or, I suppose, you could simply get a Spee3D supersonic 3D printer.

I’m curious to see how the traditional 3D metal printing companies move forward on these issues.

Via Phys.Org