Selling commercial 3D printers is an unusual business, but there seems to now be another way to do so.

Traditionally, large equipment has been sold through what’s known as resellers. These are local or sometimes regional operations that don’t make equipment, but simply make arrangements with various manufacturers to deliver their equipment (and materials) to clients within their zone of operation.

It makes much sense because the art of selling and support is very different than that of manufacturing machines. Successful machine manufacturers are first good at making the equipment, not selling them. Larger companies may eventually develop their own internal sales force, but that’s not often the case.

The reason for this is that resellers are (or should be) good at what they do. They have excellent client relation skills, and often have very extensive networks with prospective customers in their region. And it’s simply easier for an equipment manufacturer to push them towards resellers who can run with the product.

Another approach for selling that’s developed more recently is the direct approach, where marketing through a central website is used to sell equipment to interested parties. This is less expensive than going through resellers, but poses a major problem for equipment manufacturers because they must somehow convince prospective clients to visit their site and engage in a sales transaction. Resellers already have plenty of contacts, but a manufacturer does not.

But perhaps there is a third method of selling 3D printers emerging. In a recent conversation with Philip DeSimone, Co-Founder of Carbon, it became clear that company is pursuing a rather different approach.

Rather than organize a sophisticated network of traditional resellers or make a fancy website and wait for customers to arrive, Carbon is approaching the clients directly. So far, Carbon has been very successful using this approach, as they’ve made a number of deals with product manufacturers, such as Adidas.

The reason they’re able to do this with clients is that they’re able to directly propose radically new approaches to the client’s products by leveraging 3D printing technology in a way that, to the client, appears feasible both financially and technically.

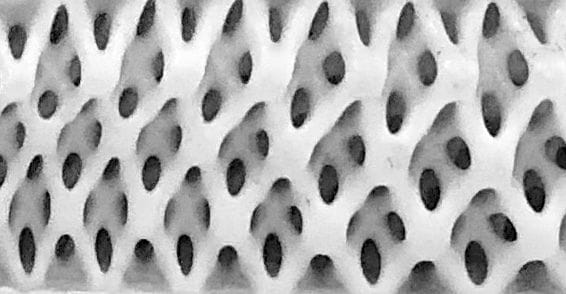

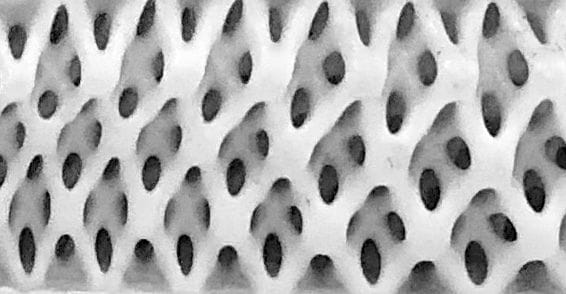

Consider their client Adidas, for whom Carbon enabled the production of highly unusual midsoles for shoes. These lattice-style shoe components were lighter and more effective than traditional designs, and indeed could not possibly have been produced using traditional methods.

Carbon needed only to convince Adidas that this was a worthy project to gain a large number of equipment orders.

What’s most interesting to me is that Adidas is but one of countless other examples of product manufacturers that could most definitely make similar use of 3D printing technology: design a new, previously-impossible product and put it into production. And do so quickly.

This sales approach is fascinating when you look at how Carbon’s sales operation must be organized. Instead of having tons of traditional sales folks or resellers running around, they need a smaller number who focus on specific companies. And behind them would be an army of technical experts able to show clients the magic that can be done.

This would lead to smaller numbers of customers, but far larger orders: sell lots of machines to fewer companies. It should work for both parties.

Aside: I should point out that Carbon doesn’t actually sell machines, but instead they lease them to clients, combined with services and materials. This means that Carbon should be able to rise on the tide of the new products made by their clients.

This approach hasn’t been used on a large scale previously, as far as I know. Companies like Stratasys do have the armies of technical folks, even specialized in different vertical industries, but they’re to support the resellers, not working directly with the clients. In this way I think Carbon has a bit of an advantage, as the resellers may not be the best folks to identify radically new product designs.

Via Carbon