Last week GE announced they’ve completed an actual test of their long-awaited new turboprop engine.

This is kind of a big deal, as this particular engine is notable for multiple reasons. Not only is it the first entirely new turboprop engine they’ve designed from scratch in over 30 years, but the way it has been made is very different.

There have been “non-flight critical” 3D printed parts used on many aircraft for some time now, but “flight critical” is quite another matter. An engine is most certainly flight critical and would need to undergo rigorous certification before use.

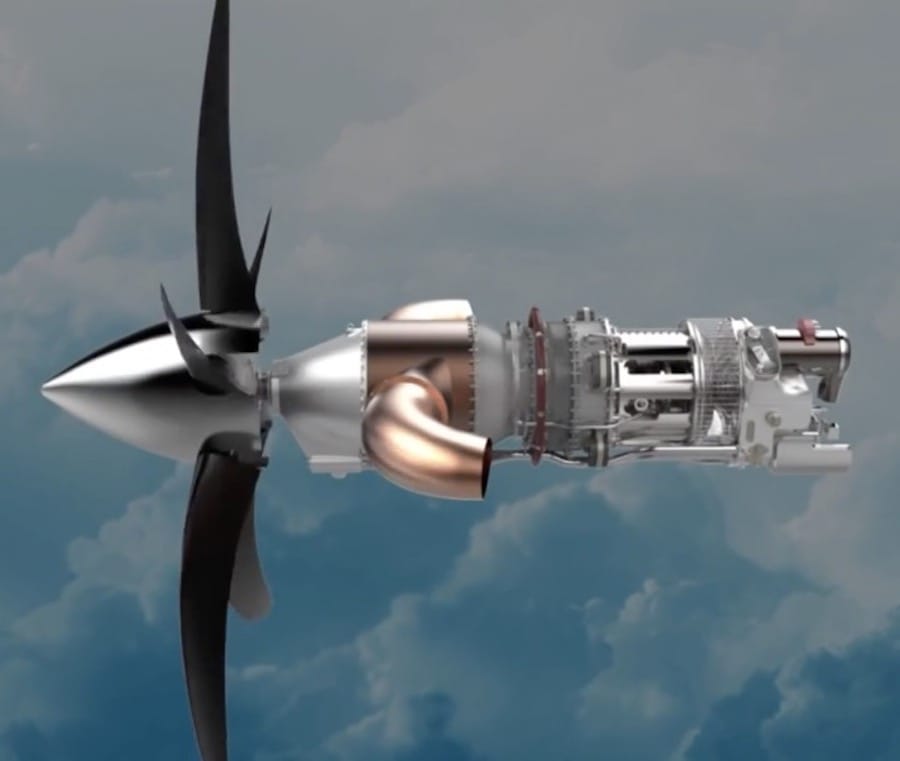

GE says 79 different new advanced technologies have been employed during the making of the “Advanced Turboprop Engine”, and one of the most prominent has been 3D printing.

GE announced this engine some time ago with great flurry as a way to let the market know they had been developing more advanced approaches to engine design. The engine design leverages the advantages of 3D printing to make a rather unusual engine.

The ability to 3D print metal components enabled GE to collapse 855 parts in the traditional design into only a dozen. This was accomplished by using more complex geometry components that is impossible to produce using casting or milling. Apparently some 35% of the engine is made using 3D printing techniques.

The effect of the fewer parts is significant, not only because there is less labor required to assemble the engine, and fewer points of potential failure, but a significant reduction in overall weight. This is due to the elimination of the many lugs and bolts that would have been required to hold the 855 parts together.

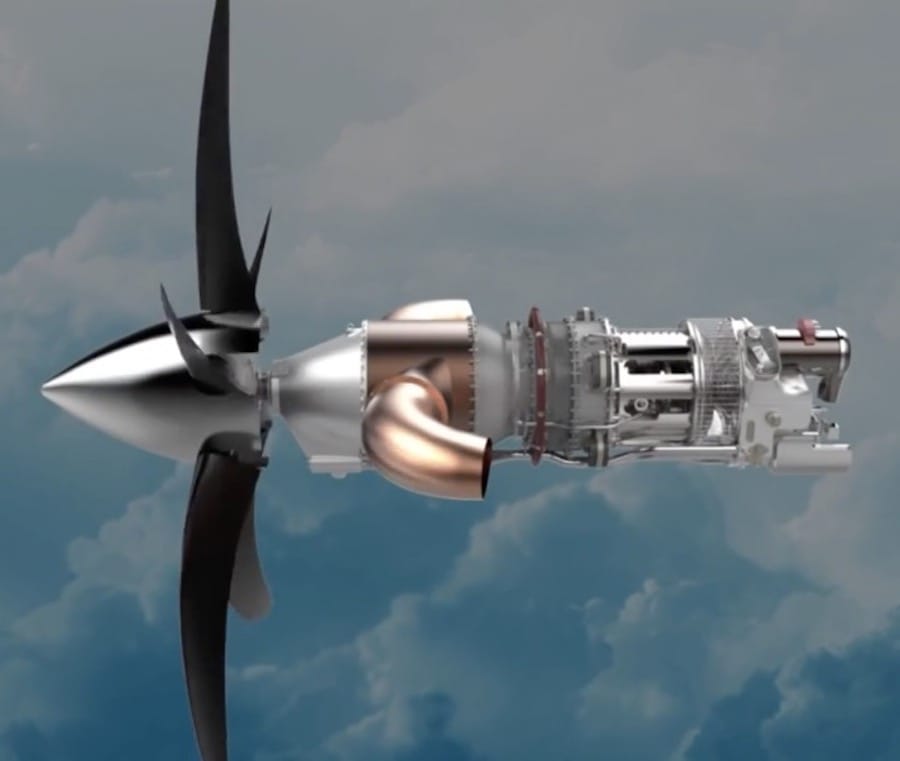

And this is where it gets really interesting: the lower weight means the engine can be effectively more powerful than similar engines, and this translates into lower operating costs. That’s extremely attractive to airlines, who typically run their businesses at the thinnest of margins. The engine, if installed in aircraft, could enable an airline to scoop up considerable additional business by lowering prices, or making more margin on existing routes.

So far, this has only been theory. But this past week GE took a big step to making this a reality by performing a successful “first engine test run”. In other words, they got the engine running, and it worked.

While quite a milestone, there is a very long way to go yet before we see this engine installed in an operational aircraft, which by the way, will be a Cessna Denali. Flight tests of this configuration are scheduled for late 2018.

I see this as a very important transition for not only the aerospace industry, but others. GE has been pioneering this approach for several years and is now it is very close to fruition. Others in the aerospace industry have been observing closely and no doubt have similar plans, but are likely behind GE in many respects.

The big effect in the future could be that this milestone could convince, or at the very least, make other many industries of the benefits of 3D printed designs. If GE can do it, why not others? I’m sure many more conservative industries want to see this actually work before they commit their resources into a deep 3D print design transition.

Like anything else, a change takes place in steps. This is one of them.

Via GE Aviation (Hat tip to Andrew)