A startling piece suggests that the concept of 3D printing may have been first conceived in Victorian England, almost 160 years ago.

This is based on a long letter written to the one and only Michael Faraday, who helped develop the principles of electromagnetism. The letter describes in some detail a “Making Machine” that seemingly used selective deposition to produce unusual objects, such as a Klein Bottle.

Unfortunately, the letter is written by one Ernest Glitch, a fictional character conceived by author Roger Curry. Curry wrote the eBook “The Ernest Glitch Chronicles” some years ago. Evidently Curry can’t help but write more about his fascinating characters, which seem to be “Victorian Experimentalists”. Pure steampunk.

There’s some great stuff in this piece, such as:

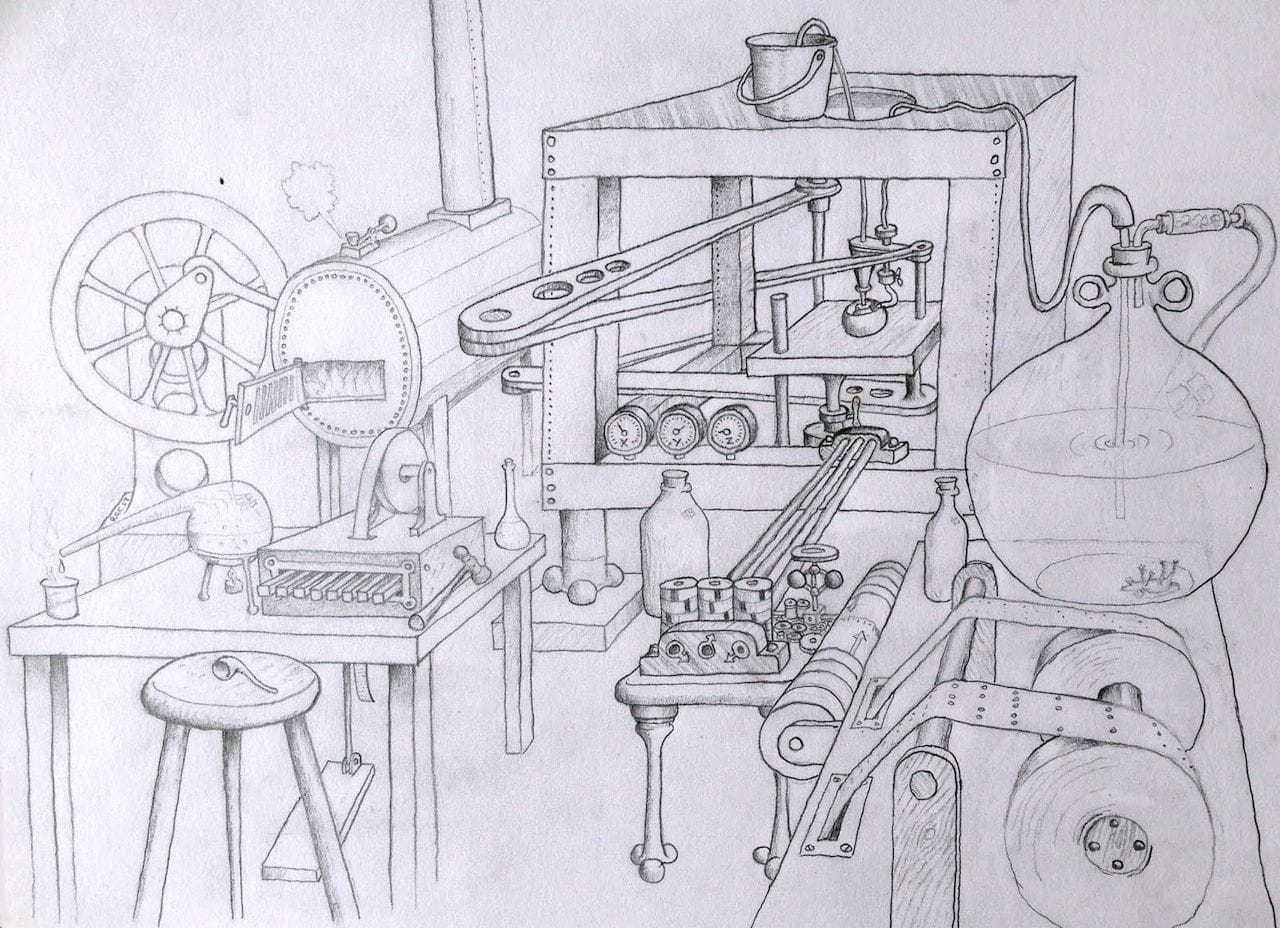

My assistant Hodges has been experimenting with what he calls a Making Machine. Suitably “instructed,” the machine slowly produces objects by squirting a paste from a heated nozzle. The nozzle moves in three dimensions, via a complex of screw threads, pantographic coupling and steam power. This machinery is precisely controlled by an analytical engine. As the paste extrudes, a curing fluid is sprayed upon it, and immediate hardening occurs. An object is built up, in layers, much as a potter produces a vase from a string of clay.

Yes, sounds like a 3D printer.

And the creations could only be of interest to perhaps craft workers, or for models to prove function and fit, toys, or to use to make a mould. Upon pointing out these reservations to Hodges, he assured me that he planned a reduction in nozzle & therefore layer size, and had in mind a future development for the machine, which I found of interest (in an engineering context with very positive overtones of financial gain). He would like the next version of his Making Machine to dispense with the extrusion of paste, and to build objects directly in metal.

This all sounds weirdly familiar.

Not only is the production of the raw making paste odious to the extreme, but the machine in operation stinks more than a back street Newcastle abattoir. The last time my nasal sense was similarly assaulted, I barely held the contents of my stomach. You will hopefully remember Faraday, my recounting of the horrific explosion at my experimental industrial-scale embalming workshops at Elswick?

Somehow this is reminiscent of the distressing algae-based 3D printer filament we tested briefly some years ago.

Please read the Glitch entire story; it’s a fun piece.

But this got me thinking. Could such a machine have been invented in 1857? What would the world have looked like if it had?

At that time there was great interest in industrialization, and the application of steam power towards manufacturing. In many cities were found factories that employed long belts, turned continuously by a nearby steam engine, which in turn powered a variety of machines. A common making machine of the day was an automated loom to produce cloth.

The problem with all of these machines was that they were single purpose. You’d set them up and they would make stuff, but it was all the same stuff. Mass production of a primitive type, I suppose.

Any attempt at a 3D printer would likely have failed miserably as it would no doubt be less expensive to make things using mass production techniques, as it is today. Then, like now, the sweet spot for 3D printing would be in customized objects. But in those days “customized objects” meant you’re working with a craftsman. Machines could certainly not compete with the quality of a craftsman of the day.

And it’s likely the 3D printer itself could not function very well, as the tolerances required for accurate movement might have been beyond the capability of the day, at least for smaller objects. It might be possible, to print simple clay objects, however. There was no plastic available, and certainly metal printing would be near impossible to attempt.

One thing that would have been possible, though, is to program the machine to produce different objects. Yes, there were no computers of the day, aside from some thoughts and concepts from Charles Babbage.

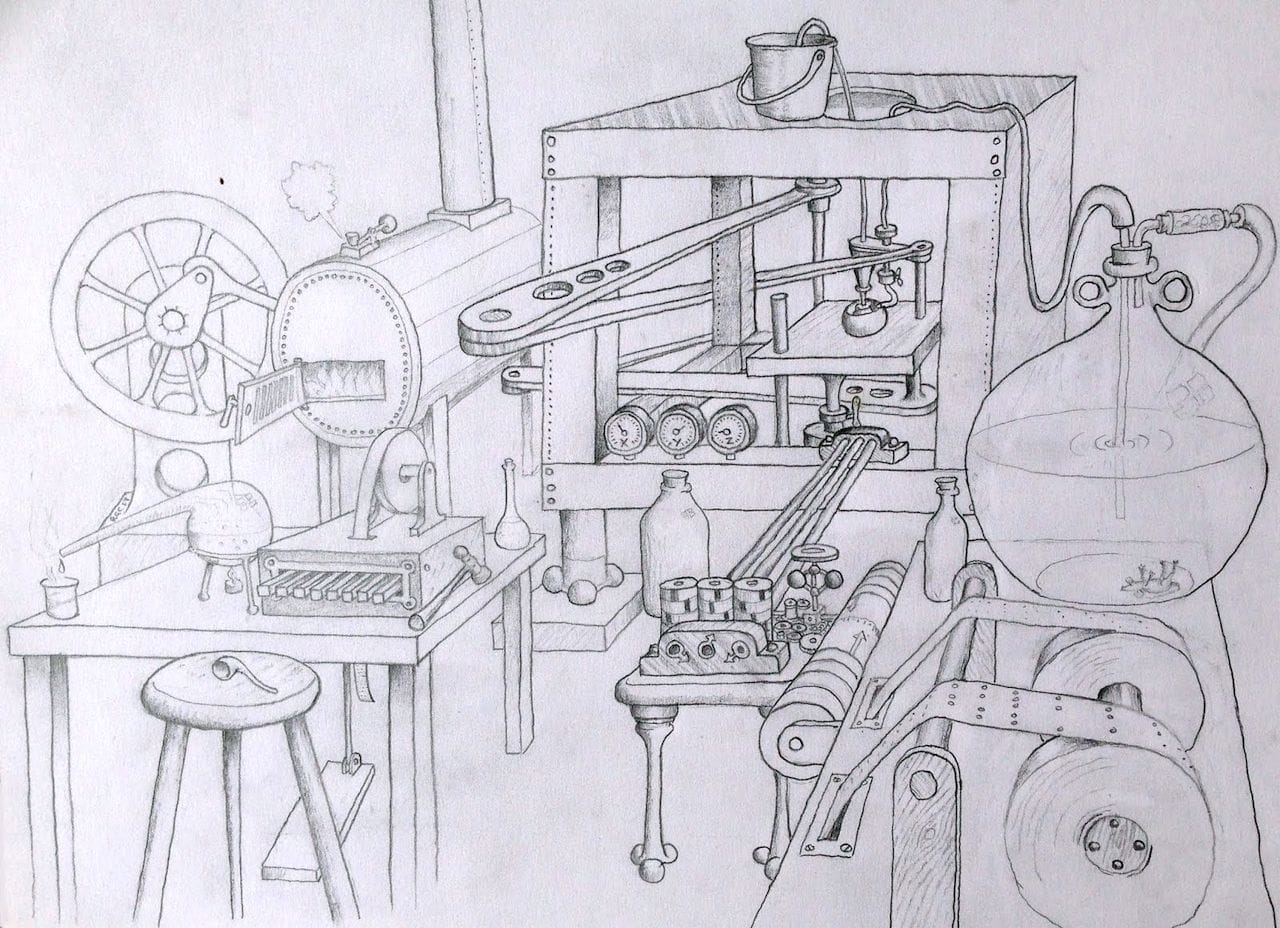

But instead of a computer you could take the “player piano” approach. This has actually been investigated by Fabbaloo friend and super-maker Andrew John Milne, who, among his many incredible creations, built a “programmable drawing machine” using 19th century technology. In this video you’ll see how it works:

In the drawing machine the arm moves in concert with a disk that’s encoded with the correct “path” for the tool head. GCODE in physical form, so to speak.

While this concept is for a 2D system, there is no reason it could not have been designed to work in 3D in a similar way. Thus if you had a reasonable extrusion capability powered by steam engines, it might have been possible to program it to print different objects.

But none of that happened, and we ended up with assembly lines making Fords, and other stuff.

Until recently.

Via Lateral Science