New research offers additional information about 3D printer particle emissions and some hints on how best to reduce them.

There have been previous studies on the topic, but generally they were establishing the foundation knowledge, simply that certain thermoplastics do indeed emit various quantities of nanoparticles at particular heat levels.

There is debate on the health issues related to exposure to such nanoparticles, but obviously it would be safer to avoid the emissions completely.

But what is the best way to do that? Ventilation is the key, but what form is most effective? Using air filtration? How about external ventilation? Local suction? Operation outdoors?

The paper, produced by researchers at the School of Public Health, Seoul National University, delved directly into these matters. The abstract:

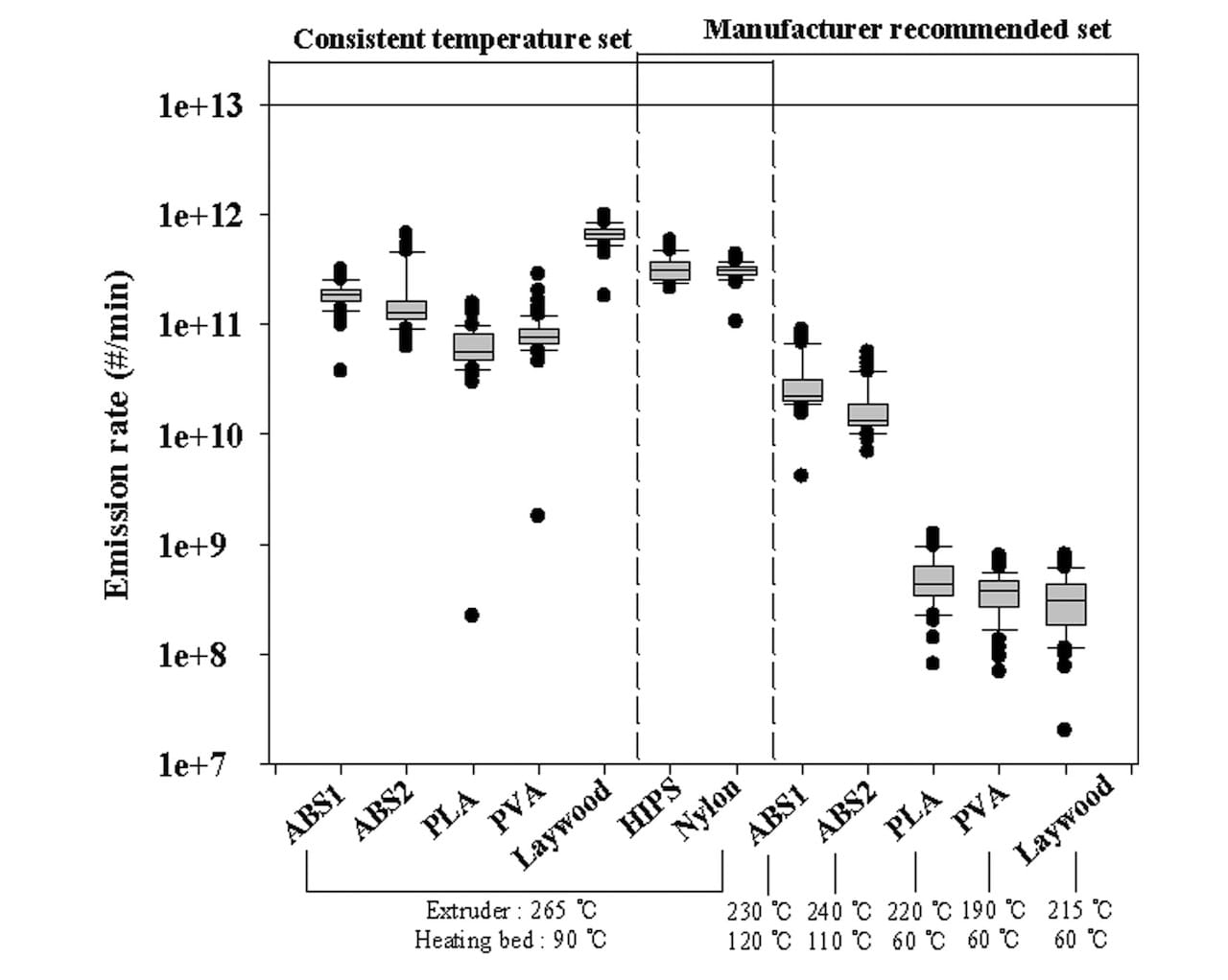

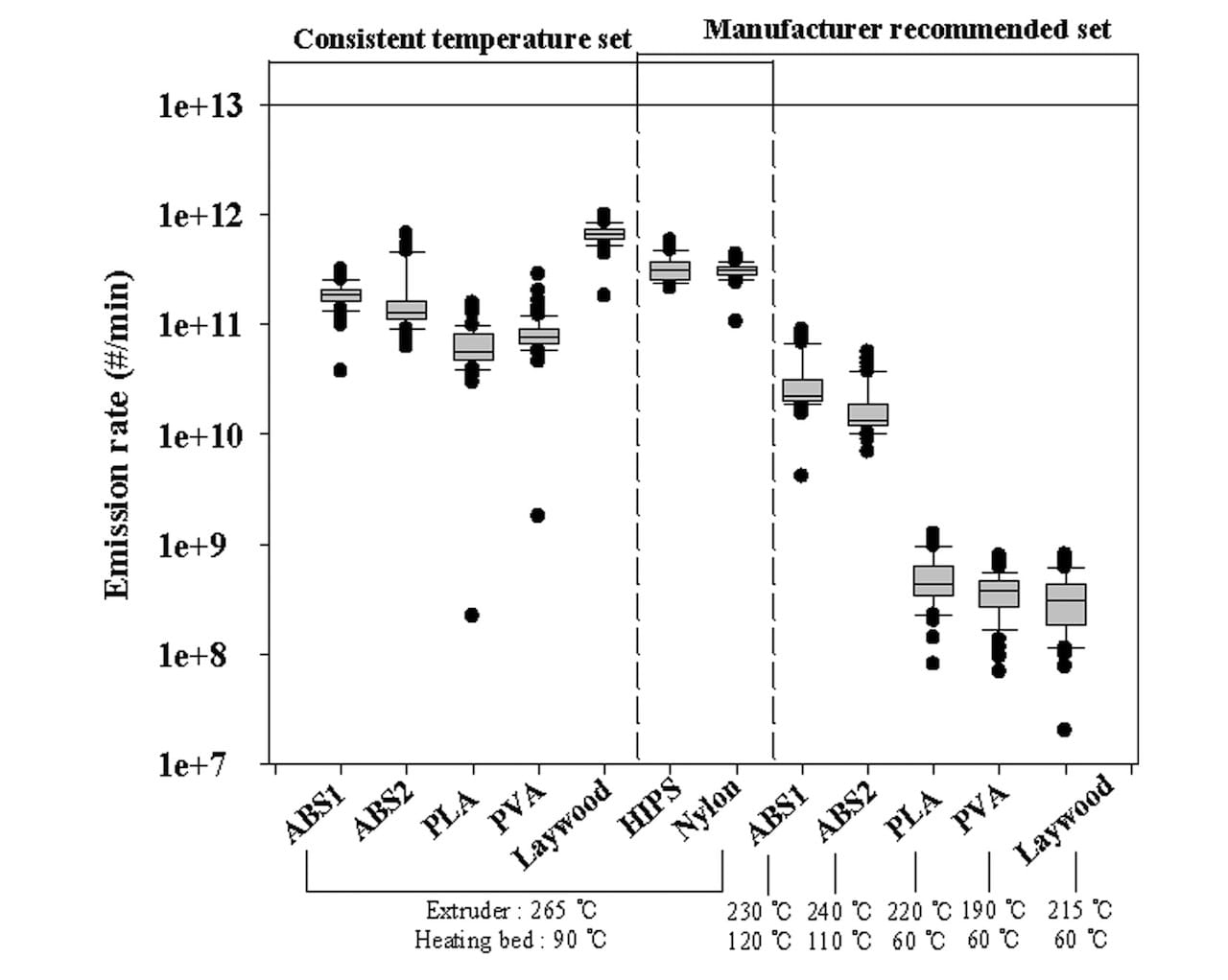

This study aimed to evaluate particle emission characteristics and to evaluate several control methods used to reduce particle emissions during three-dimensional (3D) printing. Experiments for particle characterization were conducted to measure particle number concentrations, emission rates, morphology, and chemical compositions under manufacturer-recommended and consistent-temperature conditions with seven different thermoplastic materials in an exposure chamber. Eight different combinations of the different control methods were tested, including an enclosure, an extruder suction fan, an enclosure ventilation fan, and several types of filter media.

It’s also worth noting they do offer a statement on the potential health issues of nanoparticles:

It is well-known that nanoparticles have effects on human health, including the inducement of adverse inflammatory responses. Nanoparticles can pass into the bloodstream via the alveoli and easily penetrate biological barriers, such as the gastrointestinal tract and the blood−brain barrier. Those nanoparticles can be detected anywhere in the body, and they may cause damage to DNA.23,24 Aldehydes include formaldehyde, which is classified as a human carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC: classification 1), and acetaldehyde, which is classified as a possible human carcinogen by the IARC (classification 2B). Styrene is also classified as a possible human carcinogen by the IARC (classification 2B). Emission of these specific VOCs from fused deposition modeling 3D printers was reported by recent studies.

Their experiments included testing of common 3D printer materials such as two varieties of ABS, PLA, PVA, LayWOOD, HIPS and Nylon, all of which would typically be found used in desktop 3D printers.

There’s plenty in the document, but the key findings were:

- The heated build plate does not generate substantial quantities of nanoparticles, even if a glue is applied

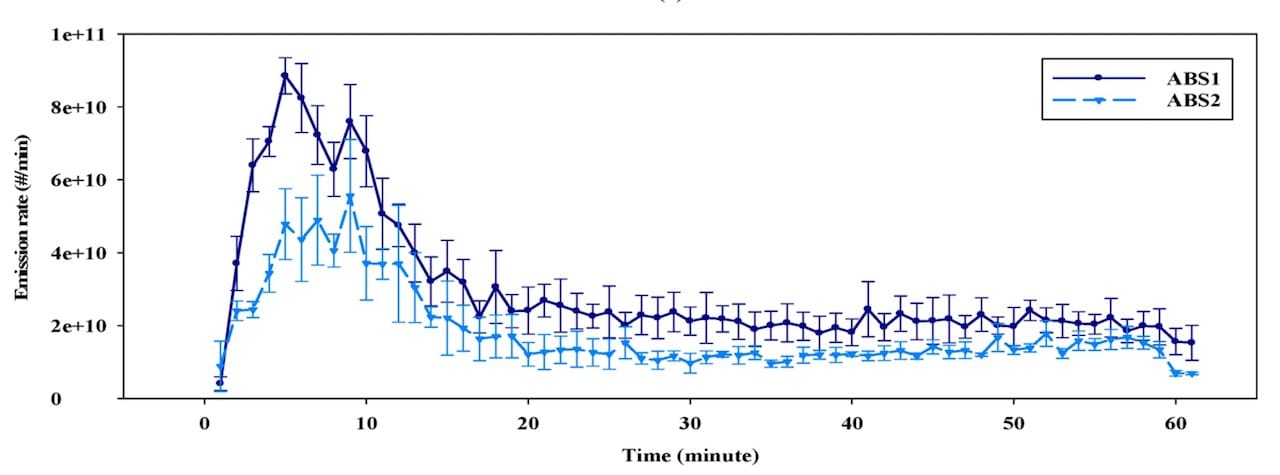

- The rate of emission tends to spike after initial heating, and then decrease over time. This is particularly pronounced with ABS thermoplastic.

- While proper room ventilation is most appropriate, an enclosure is the most effective standalone solution, if the correct filters are used.

- The “correct” filter is a HEPA style:

The ‘enclosure with ventilation fan (HEPA filter)’ method with ABS had the highest removal effectiveness, and it also had 99.5% removal effectiveness when the HIPS thermoplastic filament was used.

I hope that research of this type will be used to enable manufacturers to standardize on filtration solutions for desktop 3D printers. At the least, it should encourage those with filter-less 3D printers to consider obtaining an enclosure.

Via ACS