Profitability of 3D printing often depends on efficiency, and that’s something of prime concern to many 3D print operators.

You might classify 3D printers into two categories: “single object layer” and “3D volume”.

The first category refers to the more common 3D printers using SLA and plastic extrusion processes, and I suppose, Stratasys’ PolyJet process. In these methods you really can print only a single object vertically. While you can fill your build plate with objects, you cannot stack them up on top of each other.

This is quite different from the “3D volume” category, which might include powder-based processes such as SLS, DLMS, and similar, where the objects are printed within a volume of powder. The powder provides support for overhangs, making it possible to “stack up” objects within the 3D build volume, quite unlike the “2D” approach of the former category.

This 3D capability has some interesting advantages.

One advantage is that you can fit more parts into a single build job in 3D than you could if limited to 2D plating. This is especially important for processes that incur a fixed overhead of cost, labor and time per print job.

If you can jam more parts into a print job, you defray your costs over more parts, lowering the effective cost per unit and making the operation more financially efficient.

And so we find anyone operating such 3D equipment spends the effort to find the best way of “Tetris-ing” their parts into print volumes. This can be quite difficult.

There are some software solutions that take an arbitrary set of incoming parts and arrange them in the most optimum 3D configuration. The idea is that the optimum configuration would be the smallest size; as such, you could possibly add more parts to “fill” the build volume for the typically overnight print job.

But there’s another twist to this dilemma: you can not only arrange the parts, but you can design them to fit more optimally together.

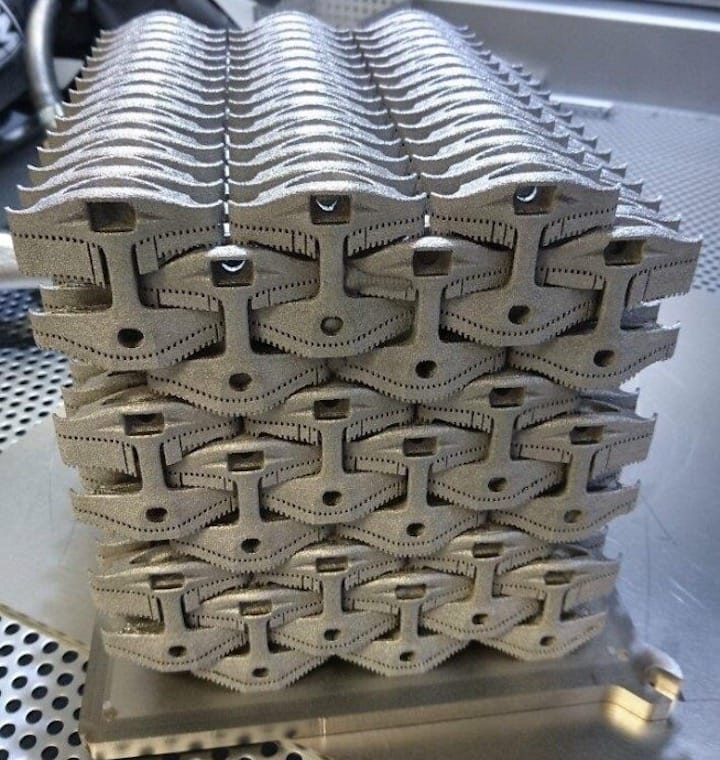

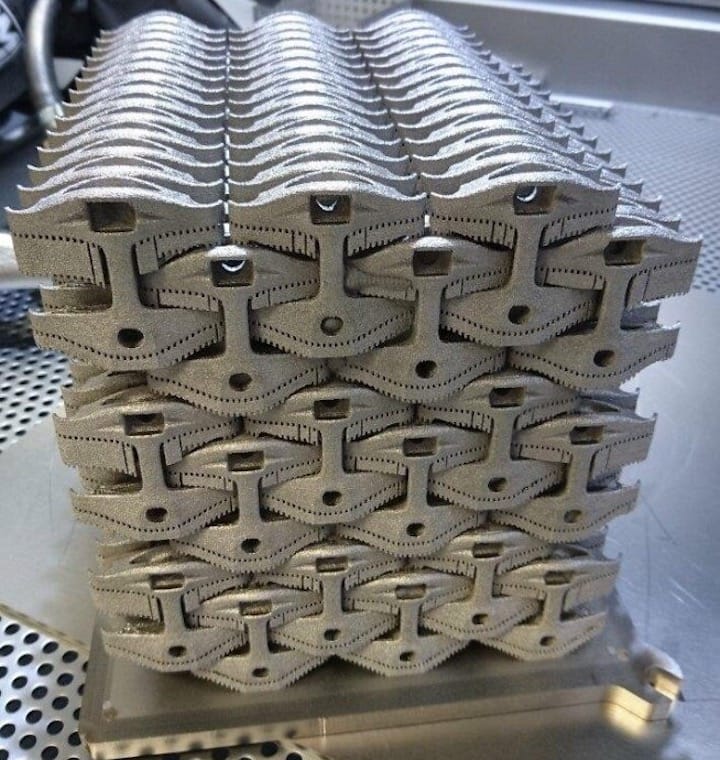

Consider this example I saw in a report on The Engineer, where an extreme example of “dense build” took place. In the image at top, Metron Advanced Equipment squeezed in no less than 252 bicycle seat brackets into a metal print job that took 102 hours to complete, consuming 6kg of metal. Apparently the space between the brackets was as small as only 1mm!

But this is the goal: when you run a 3D printer, make it count. Make as many things as possible during each and every print run. That is how those operating large 3D print farms make their money, and you can too.

Via The Engineer