What will it take for robotic-based systems to dominate 3D print mechanicals?

Most 3D printers today utilize one of several layer-based mechanical systems to move around their extrusion/deposition/laser fusing/binder jets. These mechanical systems assume the print sequence is a series of planes (layers) that are applied successively. Layers build upon each other, and eventually create an entire 3D object.

As I’ve watched many such systems in operation for years, I am always thinking of how to make the movements more optimal. But the constraint is always the fact that each layer must be completed before the next can be attempted.

This means that there could be many more movements required. Consider the case where a layer has multiple non-contiguous sections; in this situation the active print head must repeatedly move between the sections, potentially adding a lot of unproductive travel time. If only the printer could work on entire contiguous sections, one at a time!

You can sort of do this with some 3D print slicers, which offer the possibility of printing independent STL files in sequence, but there are restrictions, the main one being that one object’s shape cannot prevent the printhead from accessing the next object. But it’s not really what I’m looking for, as even within an object itself there are optimizations possible if the printhead could move in different ways.

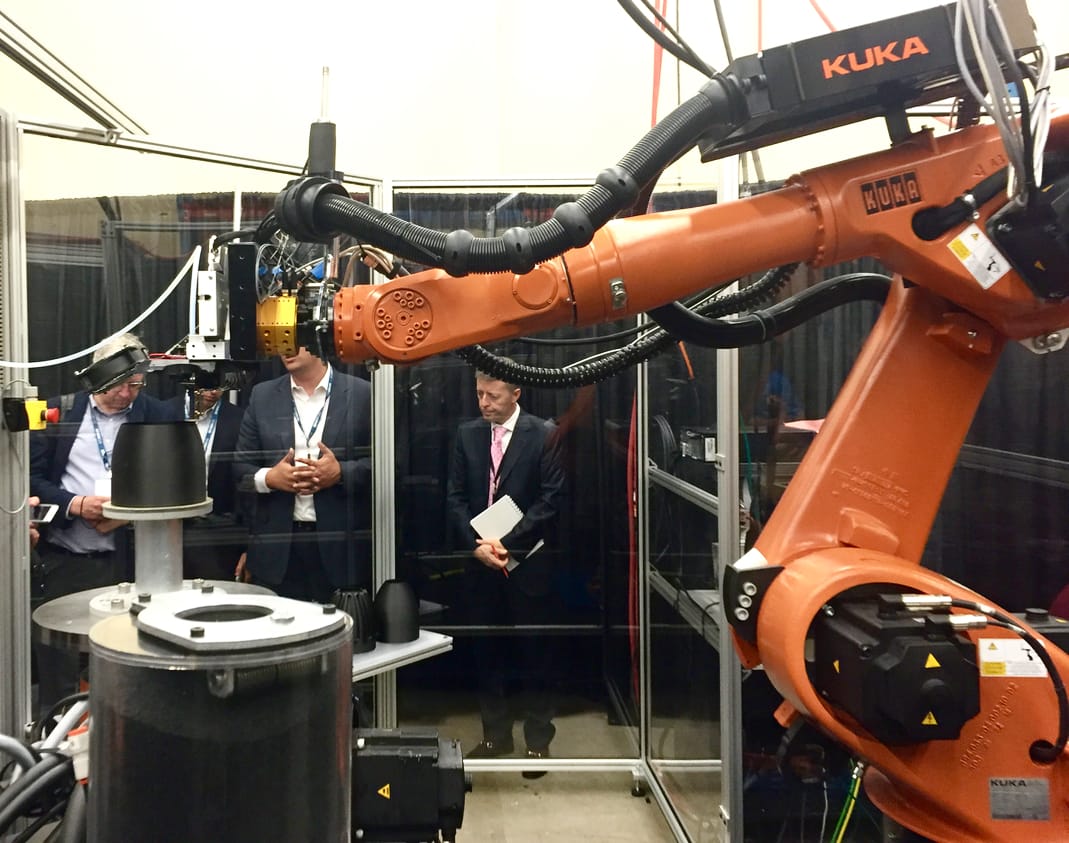

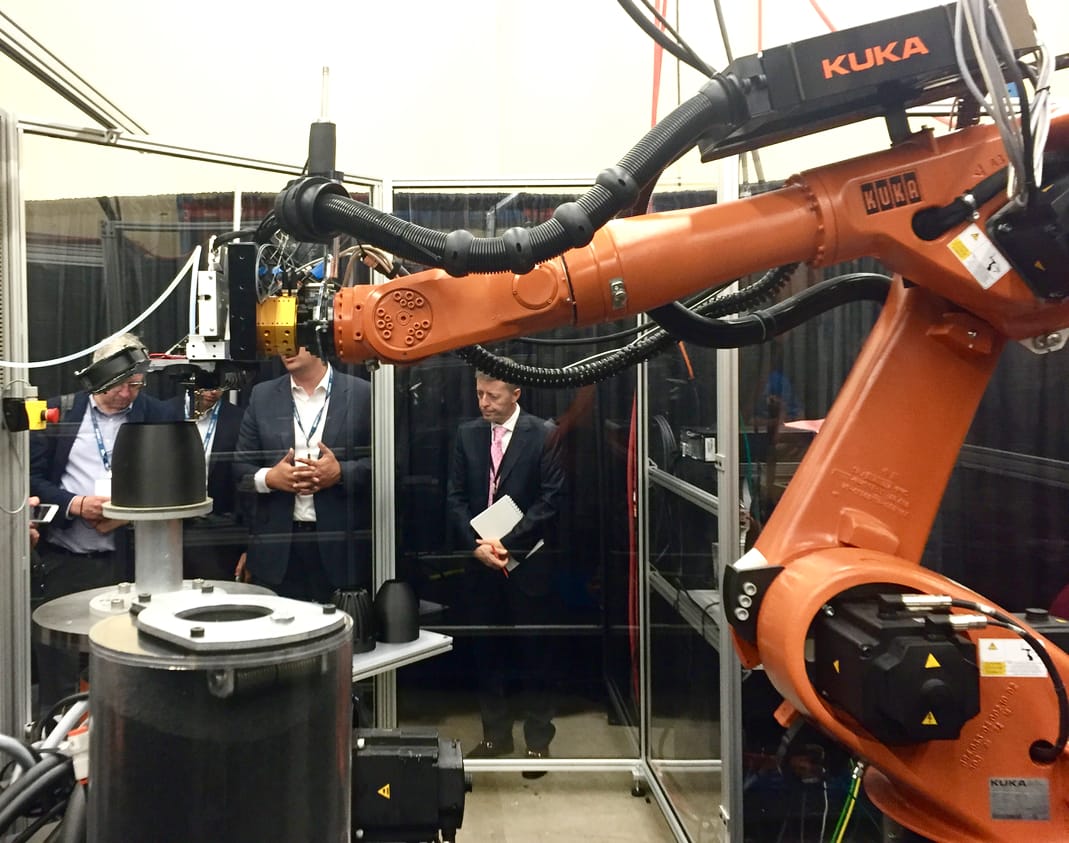

But there is a technology that could allow this to happen: robotics. While most 3D printers have their printheads mounted on some type of layer-focused gantry, a robotic system would have the printhead on the end of a robot arm that could move in many axes – six or more, for example.

A robotic system of that type could have software intelligently interpret the shape of the object and devise a far more optimal tool path.

If the robotic system is split into two segments, one holding the toolhead and the other the object being printed, then there is another advantage: elimination of support structures. The “holder” robot turns the print to an orientation where an extrusion or deposition does not require support. Temporarily printing upside down, so to speak.

There have indeed been a few 3D printing systems developed using this robotic approach. A couple of large-scale metal deposition systems make use of robot arms, and one of Stratasys’ new demonstrators used the toolhead / holder design.

It seems to me that this form of mechanical system would be far more powerful than the typical gantries one sees in many 3D printers. So why doesn’t this approach have more popularity?

There are two reasons for this.

The first reason is that robot arms, typically the less expensive versions, are not sufficiently accurate when positioning their toolhead. Today’s 3D printers often boast of resolutions and accuracies in the sub-100 micron range. If a robot arm cannot reliably position itself at that accuracy then it would not be able to produce good quality prints.

At larger scales, fine details are less of a concern, and this is why we sometimes see robotic systems performing large 3D prints, but almost never at the small scale.

The second reason for the near absence of robotic systems in small scale 3D printing is simply the cost of the robot arms. While the price of robotic equipment has been dropping, it is still far greater than the price of a gantry system. Designers of smaller 3D printers would avoid robotics simply because of the price.

Equipment operator attitudes support this decision, as the longer print times incurred by non-robotic 3D printers are mostly tolerated. If an overnight print takes 6 hours instead of 8, does it really matter?

I suspect we will continue to see gantry systems prevail on most 3D printers for the foreseeable future.