I’m reading some research from last month where a new process was used to create graphene, but there are some other implications of the discovery.

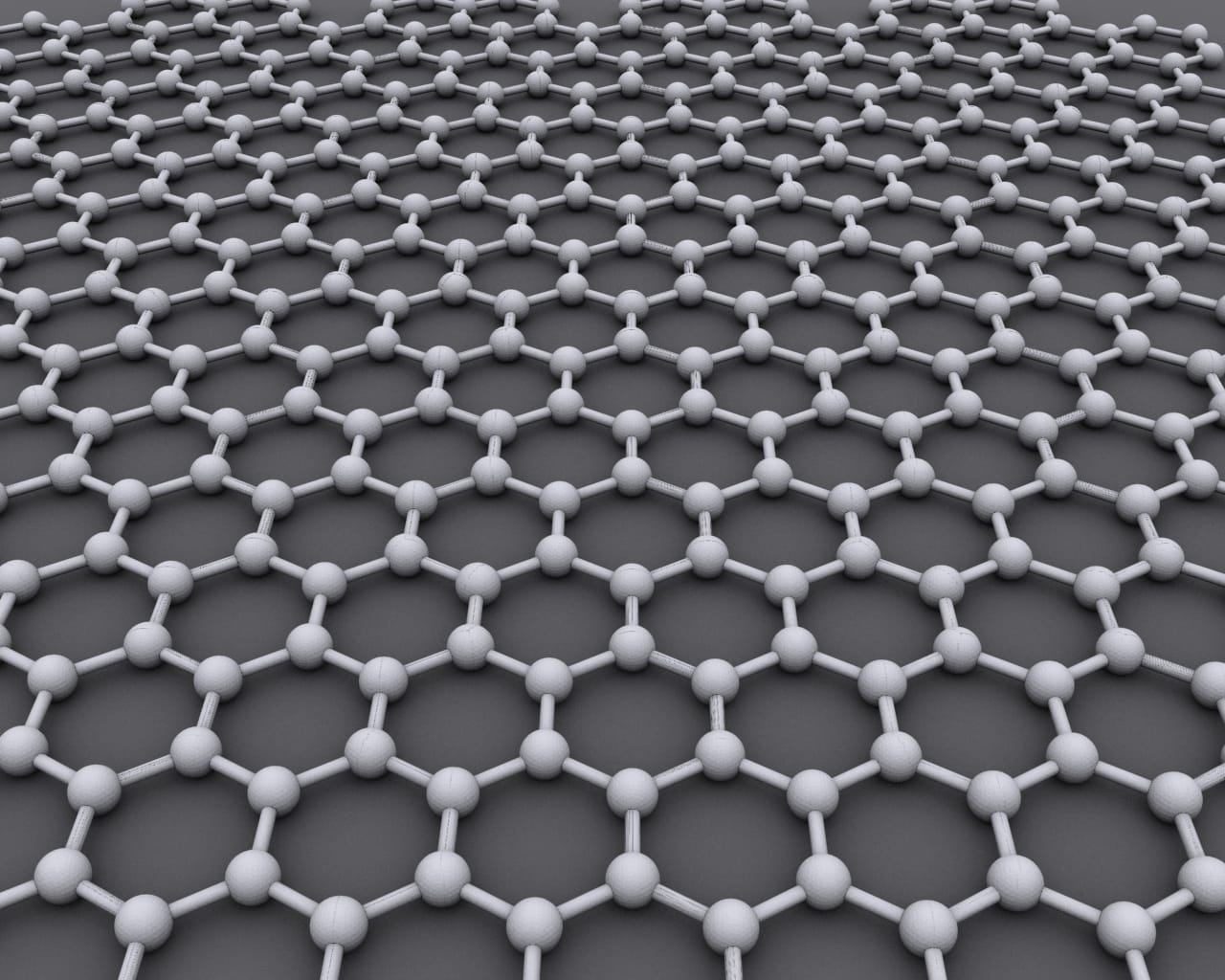

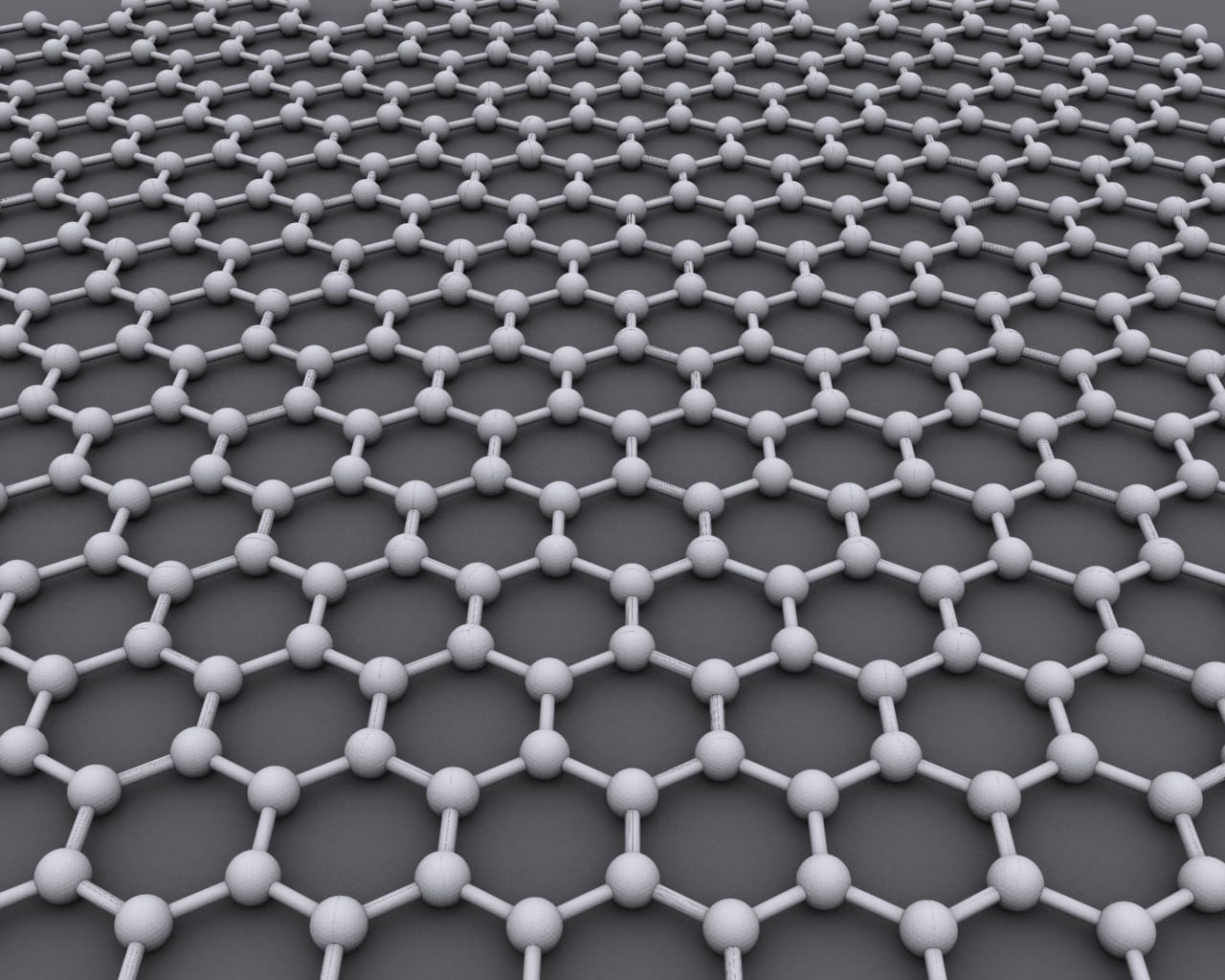

Let’s back up a bit. Graphene is a form of plain old carbon in which the atoms are arranged in a hexagonal pattern as shown above. This arrangement creates a material that has several incredible properties:

- It is ridiculously strong – said to be the strongest material known, and perhaps 200x as strong as steel.

- It conducts heat extremely well.

- It is incredibly light, as it is composed of only a single layer of carbon atoms.

- It conducts electricity with almost no resistance.

- It is nearly impermeable to many substances.

It’s a kind of “supermaterial” that could be use in any number of ways. Imagine the applications this material might have in the electrical industry, or vehicles, or aircraft, etc. You get the idea.

The problem is that graphene is a two dimensional sheet, and most things we want to use are three dimensional. Many studies have attempted to produce graphene in three dimensional form, but those that have succeeded have involved expensive and lengthy processes that are impractical for common use.

Now some researchers from Rice University and Tianjin University have leveraged a 3D printer to produce what they call “graphene foams” relatively inexpensively.

Here’s how it works: A powder-bed laser 3D printer was repurposed for production of graphene foam. Instead of lasering a plastic powder as the 3D printer was originally designed, the researchers substituted a special powder mix containing nickel and brown sugar (yes, sugar!)

The laser struck the powder surface as it normally does, but instead of melting the powder and fusing it into a solid object, a chemical reaction occurred. The sugar instantly decomposed into carbon, which sugar is basically made from, and the nickel was used as a catalyst whereupon graphene foam appeared.

This is a relatively simple process to execute once you know the correct settings for the machine and material configurations. Apparently the researchers spent considerable time experimenting with countless combinations before arriving at a set that could reliably generate graphene foam.

This is wonderful, and may perhaps lead to more accessibility to graphene foam, but I think there is something deeper here.

It seems that these researchers used a 3D printer in a very different way: the system was producing materials, not objects. I’m now wondering if there are other chemical reactions that could be made to happen using similar approaches?

If raw input materials can be powdered, then this could be a way to mix them in ways not easily done in other equipment, as the 3D printers are designed to be extremely precise in their movements and power output. Tuning prints is a common tasks among 3D printer operators, but perhaps it might also be one for materials researchers.