I’m a sucker for an entirely new 3D printing process, and that’s what I walked into when I encountered Fabricsonic last week.

Clarification: Fabricsonic’s 3D printing process isn’t exactly new, with them starting operations in 2010; it’s just new to me – and it may be new to you, too.

Fabrisonic produces a 3D metal printing device that uses ultrasonic welding principles. Ultrasonic welding is defined by Wikipedia as:

Ultrasonic welding is an industrial technique whereby high-frequency ultrasonic acoustic vibrations are locally applied to workpieces being held together under pressure to create a solid-state weld. It is commonly used for plastics, and especially for joining dissimilar materials. In ultrasonic welding, there are no connective bolts, nails, soldering materials, or adhesives necessary to bind the materials together.

Basically a high frequency sound is applied to two adjacent materials, which then causes the two materials to bond. The process is quite fascinating as it actually does not involve heat: the metals are not melted. Instead what happens is that the surface oxides on the metal parts are dispersed by the high frequency sound, leaving “raw” metals to touch each other. Local molecular motion causes the two pieces to bond together, as “strong as any weld”, they say.

That’s the principle of ultrasonic welding. But how do you make a 3D printer from this?

A spin off from Columbus’ Edison Welding Institute, Fabrisonic’s concept involves presenting thin sheets of metal to a movable “Soundtrode”, the part of the machine that issues the ultrasonic waves. As the soundtrode passes over the two adjacent sheets, they are bonded together using the ultrasonic welding effect.

The key is to move the soundtrode in the shape of a layer of the desired 3D model. Then after repeated application of sheets and soundtrode, you have a completed, solid print.

There’s just one problem: there are sheets of unbonded metal still loose. These are simply trimmed off after the print completes with a CNC mill, leaving a fine metal object.

The prints are actually of quite high quality, as the CNC mill provides an excellent finish.

There are some very interesting advantages – and some disadvantages – to this approach.

Since you are supplying metal sheets as input, it is entirely possible to mix different materials, layer by layer. You can thus create 3D metal objects of dissimilar materials, such as this item, made with both titanium and aluminum. The item shown at top is made from copper and aluminum, for example. It’s also possible to pause the process and embed items like sensors within the print.

Metal sheets could be CNC cut during printing to form internal cavities and channels as required. However, I suspect there are some highly complex geometries that might not be practical with this approach.

Fabrisonic has patented this unusual process, so you can expect to see it from no other vendor anytime soon.

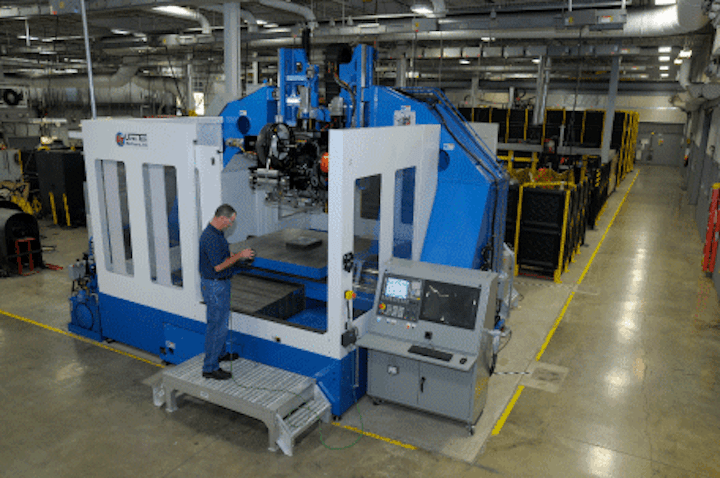

The company provides a number of different options for this machine, with office sized versions costing around USD$350K, ranging up to a large USD$3M machine with a 2 x 2 x 2m build volume, which has to be one of the larger 3D metal printing volumes available today. I get the impression they will meet your needs.

I’m not sure of the actual operating cost of these devices, but I suspect it could be quite reasonable, as the input material is simply easily obtained thin sheets of metal, and not USD$500 per kg for specially prepared metal powder that is often required in other 3D metal printers.

I’m wondering why there isn’t more attention paid to this interesting process, and speculate that Fabrisonic is yet another option in an increasingly crowded 3D metal printing market that gets tougher every week.

Via Fabrisonic