The rocket scientists at E3D-Online have been doing some rather interesting experiments with their soluble support material.

The company introduced their “Scaffold” support material, part of their spool.Works line of professional filaments, late last year. It was developed as a response to the relatively poor capabilities of dissolvable support materials at that time, most of which required the use of specialized agents to activate the dissolving process. HIPS, for example, was (and is) a popular support material, but it requires use of Limonene to dissolve it away from the 3D print itself. Yes, you can get Limonene, but why can’t you dissolve with plain water, which is readily available everywhere?

PVA was another material of interest for use as a dissolvable support product, but E3D-ONLINE found that it had poor adhesion to materials, poor melt flow, absorbed moisture and caused nozzle jams.

They set out to produce a new material that avoided or at least significantly reduced those and other operational issues. And they did so, introducing Scaffold, their proprietary dissolvable support material. And it needs only plain water to dissolve.

While this material has proven quite successful, it seems that the folks at E3D-ONLINE have been doing some experiments with alternate uses for this material, far beyond using it for mere support structures.

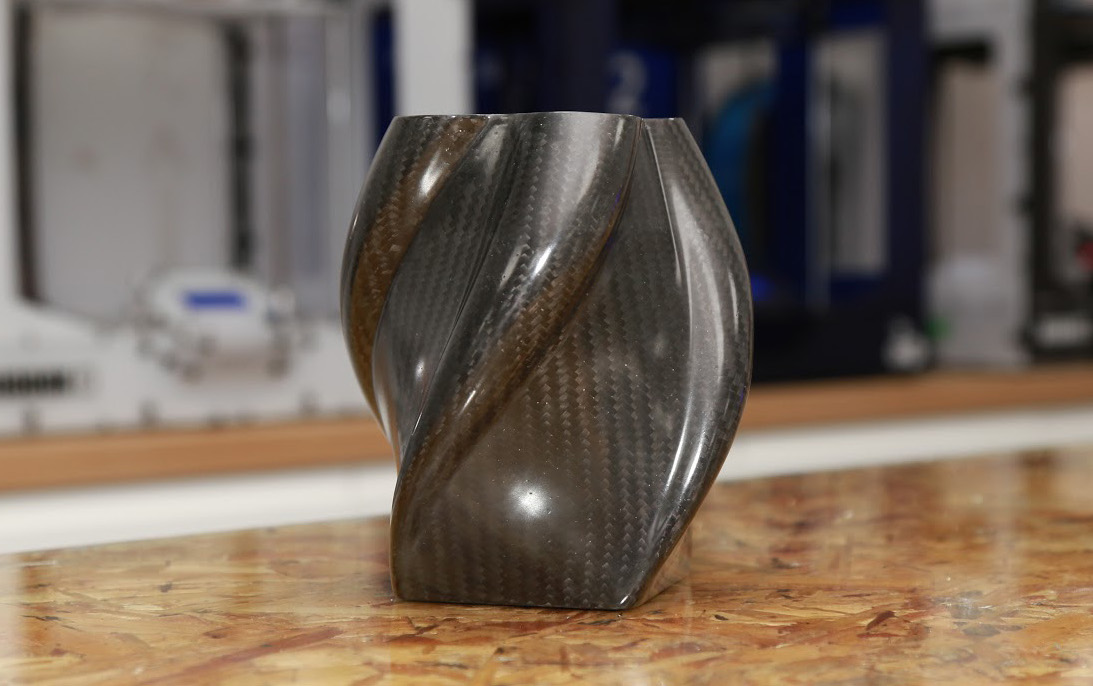

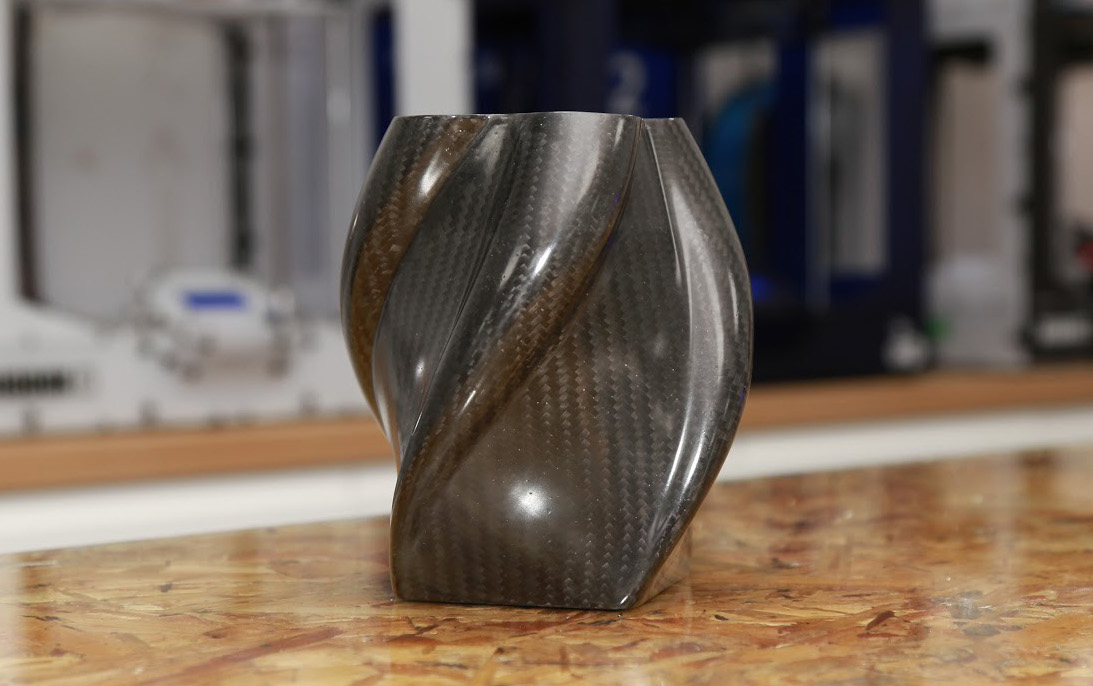

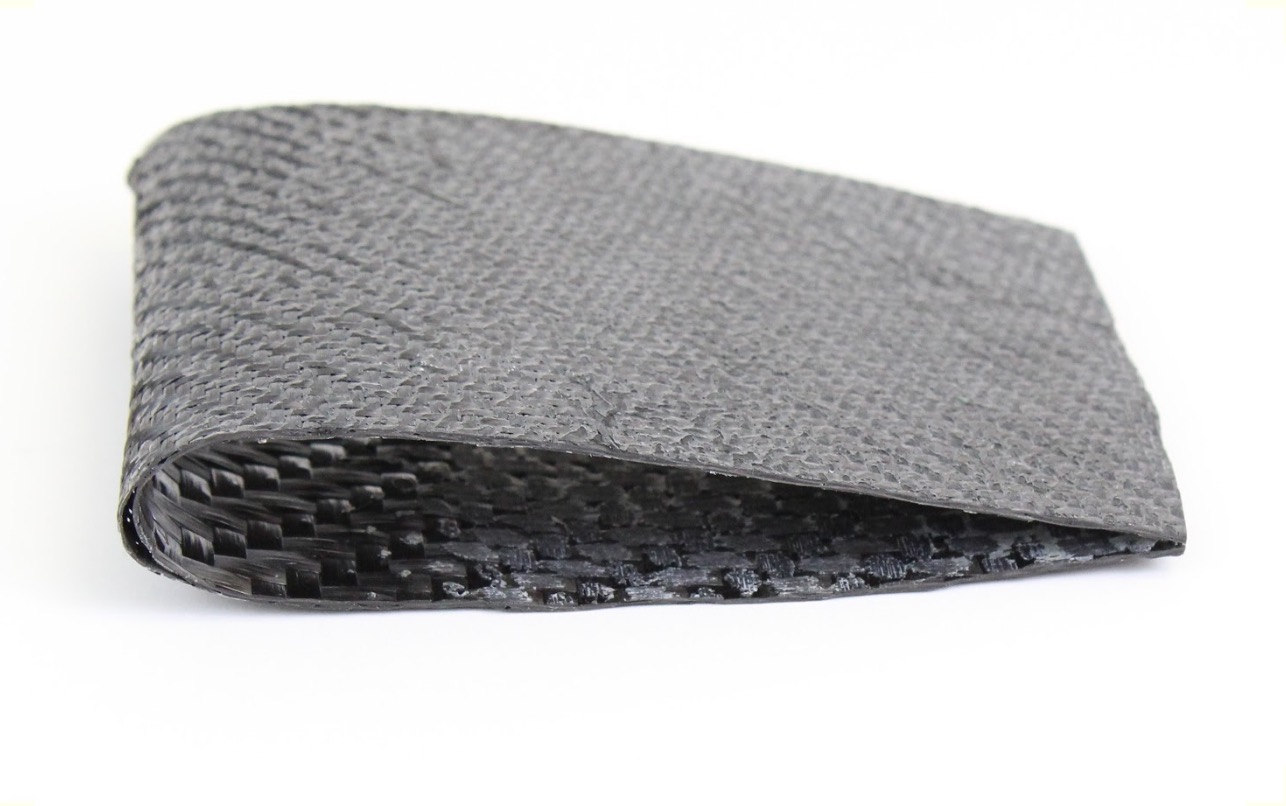

Their hypothesis was that you could make a mould for use in composite layups (such as carbon fiber). This is a process where layers of composite material are mixed with resin and cured into solid shapes. The mould holds the loose composite sheets together in the correct shape until they solidify. Parts made in this way are extremely strong and also very light, making them ideal for certain applications, such as automotive or aerospace.

The big problem in the process of such layups is to create the mould. Typically it’s done with material-wasting CNC machines that mill down metal at great expense to create the mould.

The idea here is instead to 3D print a mould, layup the composite sheets and after curing, dissolve the mould away to release the completed composite part.

The advantage is that you can produce moulds in shapes that are not possible with CNC machines, similar to the advantages found in other 3D printing applications. This means you could produce a more complex composite object in far fewer parts, as the more complex structures might have to be broken up into smaller, simpler pieces if using machining.

It seems like a good idea, but obviously requires a number of trials, and that’s exactly what E3D-ONLINE did. I won’t give you all the details, but recommend you read through their detailed sequence of experiments.

Suffice to say that they performed several experiments with simple and more complex parts, but found that their Scaffold material could not be baked at temperatures higher than 60C, lest it deform. This constrains the curing process somewhat, but it is still usable. It seems that you’d have to do multiple runs to figure out all the ins and outs of this technique.

However, they did prove that it’s quite possible to do so. And that should lead many others to use the process to begin creating strong composite objects in a far less expansive manner.

I’m also interested in the contrast between this approach and that of Stratasys, who have recently announced their goal of developing advanced 3D printers that print in composite materials directly, whereas the E3D-ONLINE approach is indirect.

And it’s also going to be a lot less expensive.

Via E3D-ONLINE (Hat tip to Richard)