The era of extremely limited 3D printer material selection seems to be ending, but what might the next materials challenge become?

Only a few years ago 3D printer operators – both desktop and industrial, were in a world with relatively few material options. Desktop machines were mostly ABS and PLA plastics, while industrial machines used ABS, Polycarbonate, Nylon and a few others. Even the PolyJet technology (from then Objet, now Stratasys) that was said to produce hundreds of unique materials, but in reality it was simply mixing two resins on the fly in fixed combinations.

Since that time we seem to have moved into a new era in which chemistry is beginning to rule. With the increase in public and industry awareness of 3D printing, chemical companies and others have brought their expertise to the 3D printing world. We’ve seen never-before-produced plastics specifically for 3D printing applications.

These so-called “miracle materials” overcome many of the constraints posed by the original materials and have enabled much higher quality 3D printing on almost every device. Of note is the increasing ability of “lesser” machines to approach the print quality of highly-tuned industrial machines. Industrial machines frequently included design features to overcome the limitations of the restricted set of materials.

This makes the space much more competitive and innovative, as companies can now beef up the capability of their machines by using superior materials instead of actual hardware changes.

It’s clear that for at least the next few years we will continue to see increasingly powerful materials change things for the better.

But what comes after that?

My speculation would be approaches that attempt to optimize the microstructure of 3D printed materials.

A key property of 3D prints is their strength, something almost always considered. The goal has been to make “stronger prints”. One way to do this is to develop a combination of material chemistry and deposition technique that ensures much stronger bonds between layers and along extrusions.

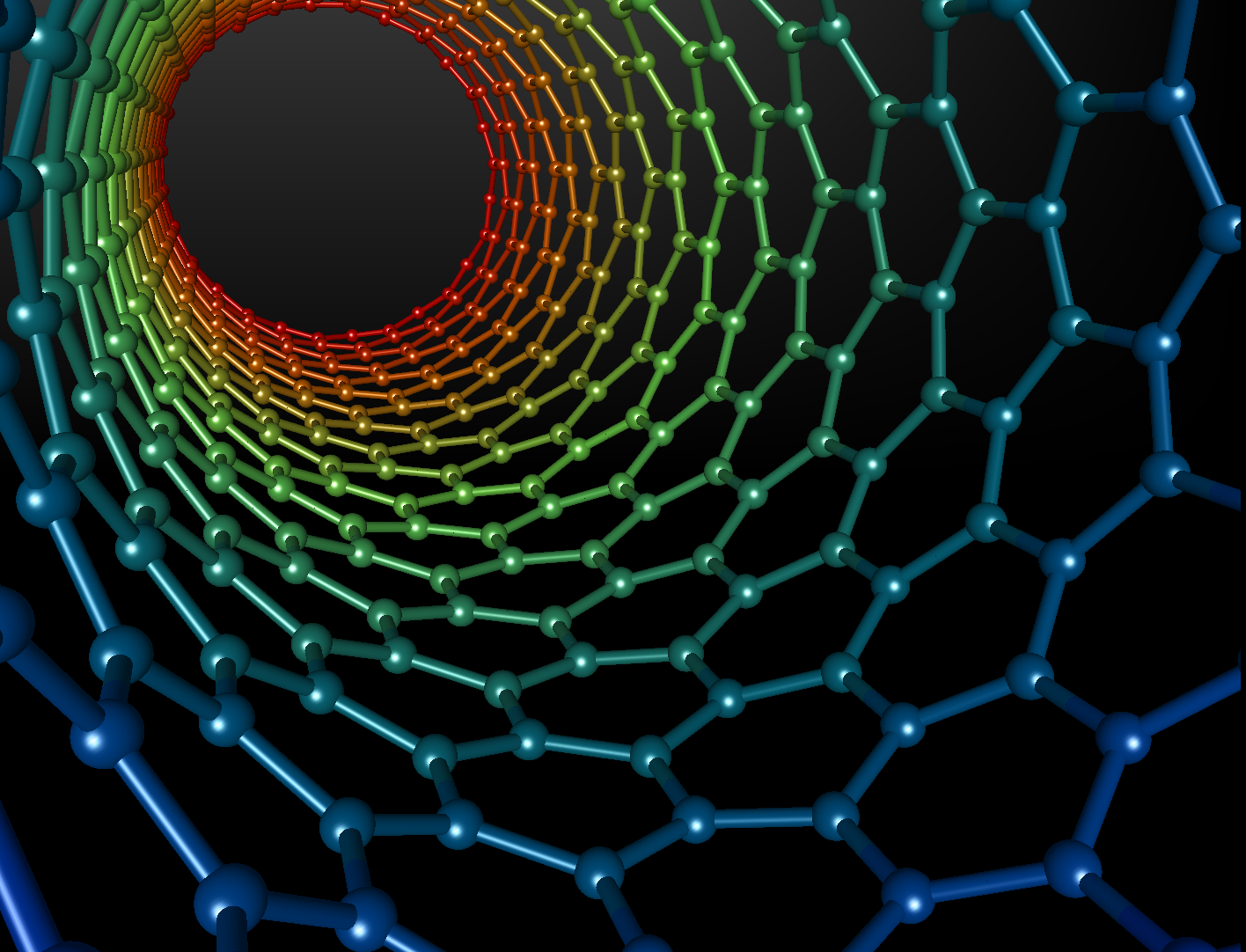

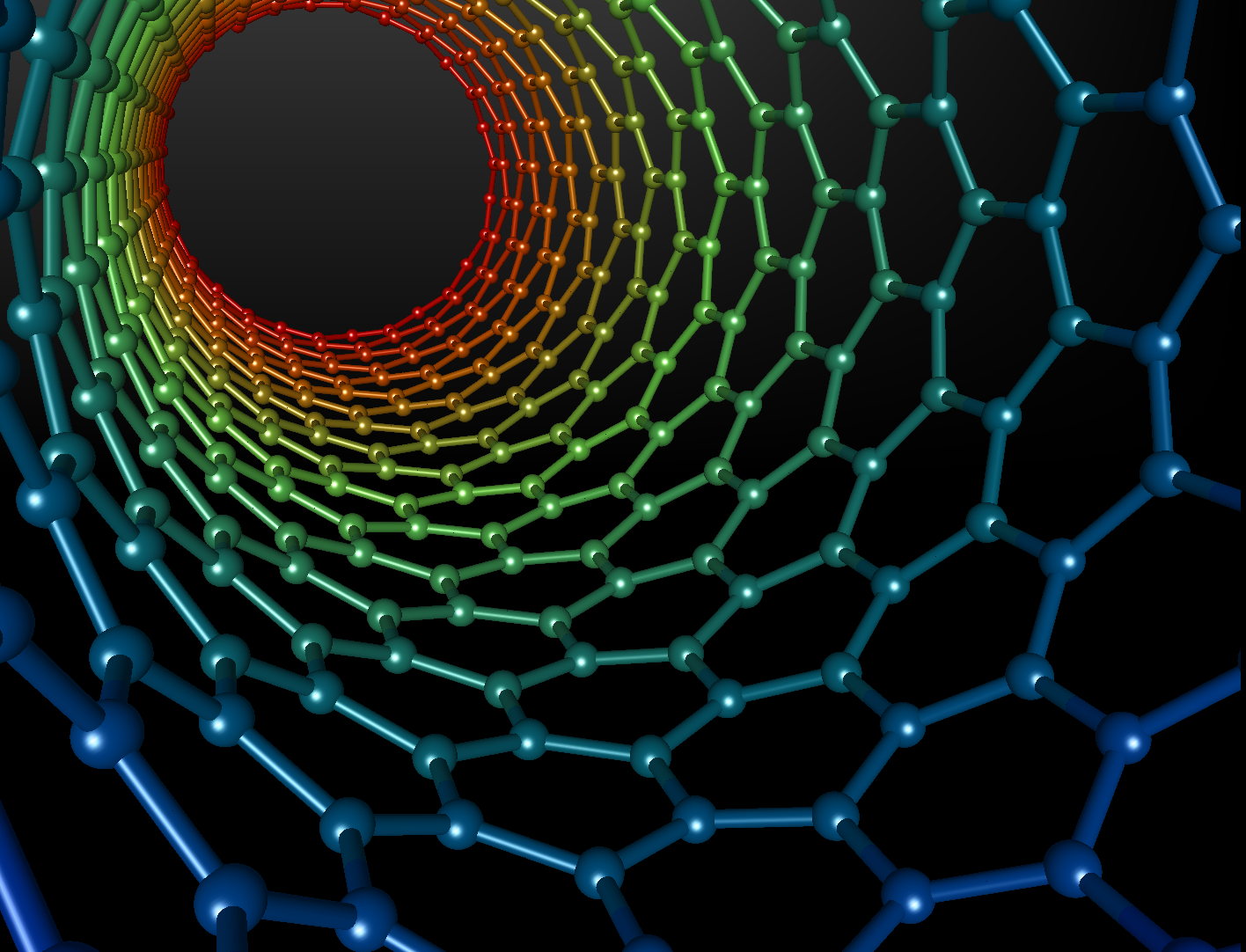

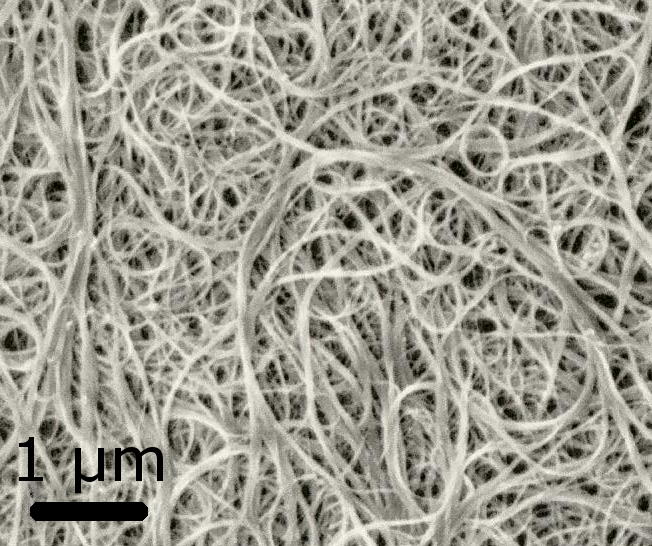

A radical example of this effect is carbon nanotubes, which are extremely long tubular arrangements of carbon atoms. These tubes are literally held together with atomic forces of great strength.

Existing carbon nanotube 3D printing products are actually made from short segments only. While they can make the prints stronger, it’s nothing compared to a print made from continuous carbon nanotubes – which, by the way, are not currently possible to produce in quantity.

Similarly, material microstructures can offer significant strength. Crystalline structures can be extremely strong, or irregularly positioned atoms can offer shock absorbing capabilities.

Imagine if 3D printing research discovered ways for machines to produce prints with such properties. Such work may be underway already in some secret research lab, but I suspect the results may not be seen for years.

When it does appear, we may have another 3D printing revolution.