I recently encountered a couple of fascinating research projects that are both attempting to develop powerful new 3D printing technologies.

Both are being developed by a similar group of parties organized in consortiums, funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program.

The first project is “Borealis”, intends on developing a more effective metal 3D printer:

Borealis general objective is to exploit a decade of advanced R&D results in mechatronics and laser processing to demonstrate a novel machine that will produce, at unprecedented throughput (up to 2000 cm3/h) and efficiency (40% energy and 75% material saving), in true net shape (no final machining needed), with closed loop controlled and certified quality (zero faulty parts delivered), large (up to 4.5 m) and complex (in geometry, functionality, composition) products.

The process uses metal powder, like many other metal 3D printers, but in a different way. Delivery of powder is done by a robot arm equipped with a “revolver” head that can switch and mix powders on the fly. The powder is dynamically melted using a powerful 3kW laser. The machine will also be able to perform material and binder jetting processes.

The other interesting innovation in the Borealis machine is a secondary laser that works with an integrated scanner to ablate the printed surface to create microscopic holes, textures and smoothing. This could potentially eliminate a substantial amount of post-processing work.

The Borealis concept involves a flexible build volume that could range from a mere 250 x 250 x 250mm to a monstrous 4,500 x 2,500 x 1,000m size. And in that volume, the intention is to enable deposition of up to 2,000 cubic cm of material per hour. This is equivalent to printing a solid five inch cube every hour. That’s fast!

Their design will also incorporate numerous other efficiency and workflow features to simplify the job of producing complex metal parts in a single machine with zero failures and consistent quality.

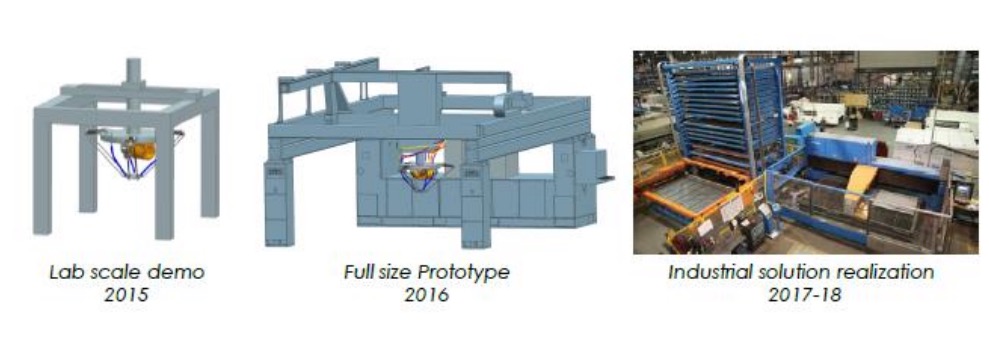

Currently, they are developing a full-size prototype of the Borealis machine, with intentions of marketing the machine in 2019.

The second interesting project is Symbionica, a venture attempting to develop a 3D printing system specifically designed to produce “personalized bionics and prosthetics”. This is their objective:

Symbionica objective is to make technically feasible and economically sustainable the production of orthopaedic smart implants/prosthesis with a level of customization never seen before: geometrical and morphological customization to tailor the implant to patient interfaces for endo-, exo- and hybrid implants made in multiple materials; functional customization to adapt prosthesis dynamic and static behaviour to patient needs (responsiveness to loads, condition based drug delivery, etc.) across the patient life.

The major hardware innovation I see in this project is the ability to freely incorporate multiple materials within the same print, a capability that could enable many different types of bionics and prosthetics than are possible today, where only single materials are typically used.

Like the Borealis, the Symbionica machine will use a variable-sized build volume, ranging from 100 x 150 x 100mm to 1,500 x 2,000 x 2,000mm. Materials being targeted include: Ti, Ti-Al-V, Carbon or Glass Fibre composite, UHMWPE and PEEK.

Also like the Borealis, Symbionica will simplify the work process by integrating several making technologies within a single machine. Through this approach, they hope to reduce material usage by 75% and energy consumption by 40%.

The Symbionica project began in 2015 and is set to conclude in 2018.

There are other similarities between the two projects, no doubt because the parties in the two consortiums are very similar. However, there are two interesting conclusions from this research that I see:

First, it appears to be the moment when the notion “3D Printing” as a standalone activity are ending. In fact manufacturing has always been a sequence of processes that result in the desired component. By recognizing this fundamental notion, leading machine vendors can build machines that directly address the workflow of industries. This style of machine should be eminently more marketable to industries as it would no doubt provide significant value in cost and time efficiency.

The second conclusion is that because these two projects appear to employ similar mechanisms, it may suggest that the standard making machine of the future might not be simply a 3D printer, but rather a more complex device that includes several technologies in a coordinated manner.

Could the days of standalone 3D printing in industry be coming to an end?

Via The Borealis Project and Symbionica