Yesterday I described about Höganäs’ incredible Digital Metal 3D printing process, but I believe there are some strong implications here.

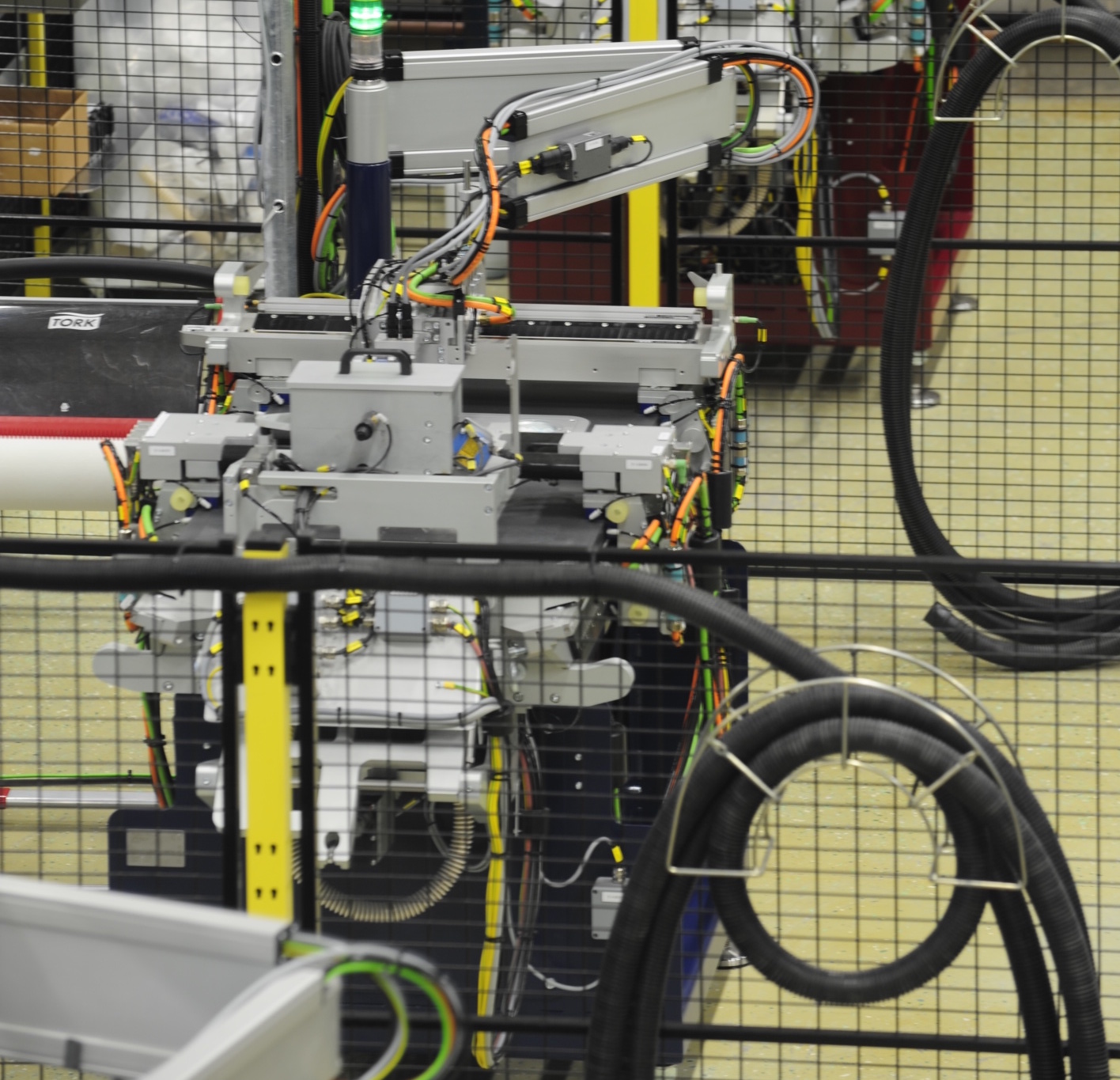

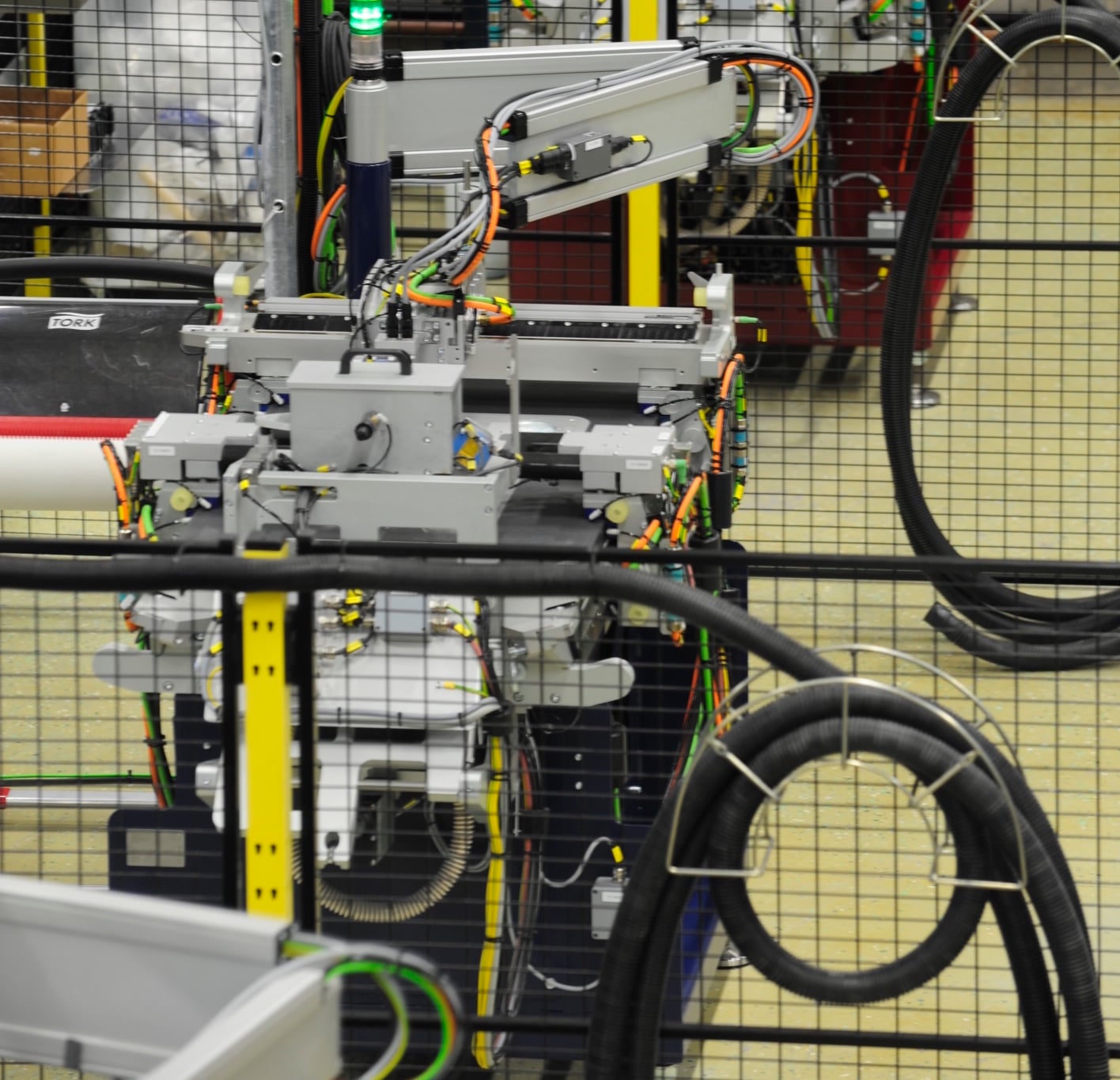

As described previously, the Höganäs metal 3D printing process is a cold process involving selectively binding powder, followed by a sintering of the bound object. The results produced by the Digital Metal process are astoundingly detailed.

What’s most interesting to me about this process is how utterly different it is from the other metal 3D printing processes that it’s a cold process.

Here’s a quick refresher on the most common method of 3D printing metal: a bed of finely powdered metal is selectively sintered by high-power laser or electron beams, layer by layer, to form a metal object.

But there’s some challenges with this approach, namely that the powder becomes dangerous when exposed to air. Some metals, such as titanium, are actually explosive when in contact with heat and oxygen. Because of this, and the need to precisely control temperatures, such metal 3D printers are usually found with controlled atmosphere chambers in which the sintering takes place. These chambers are filled with neutral gases to prevent explosions.

However, implementing that requires expensive air-sealed chambers, gas pumps, pressure monitors and more. It’s all quite involved and expensive, leading to higher machine costs. For the moment, the machine costs are high but still in a range where industry can make effective use of them.

But now let’s contrast this to Höganäs’ process: no need for atmosphere-controlled chambers at all. In fact, the sintering process is done externally to the printer, perhaps even in an existing furnace.

Höganäs’ Digital Metal process should be much simpler.

And it should be less expensive. However, the pricing on Höganäs’ DM P1000 is high at €600,000 (USD$640,000).

I see no immediate reason why the Digital Metal process could not be scaled up to much larger build volumes, as similar powder processes are already used for plastic 3D printing processes – as are metal 3D printing processes.

If Höganäs were able to scale up this system, you’d have yourself a fantastic metal 3D printer that could produce essentially finished objects that don’t require post processing in many cases. This could greatly simplify manufacturing workflows.

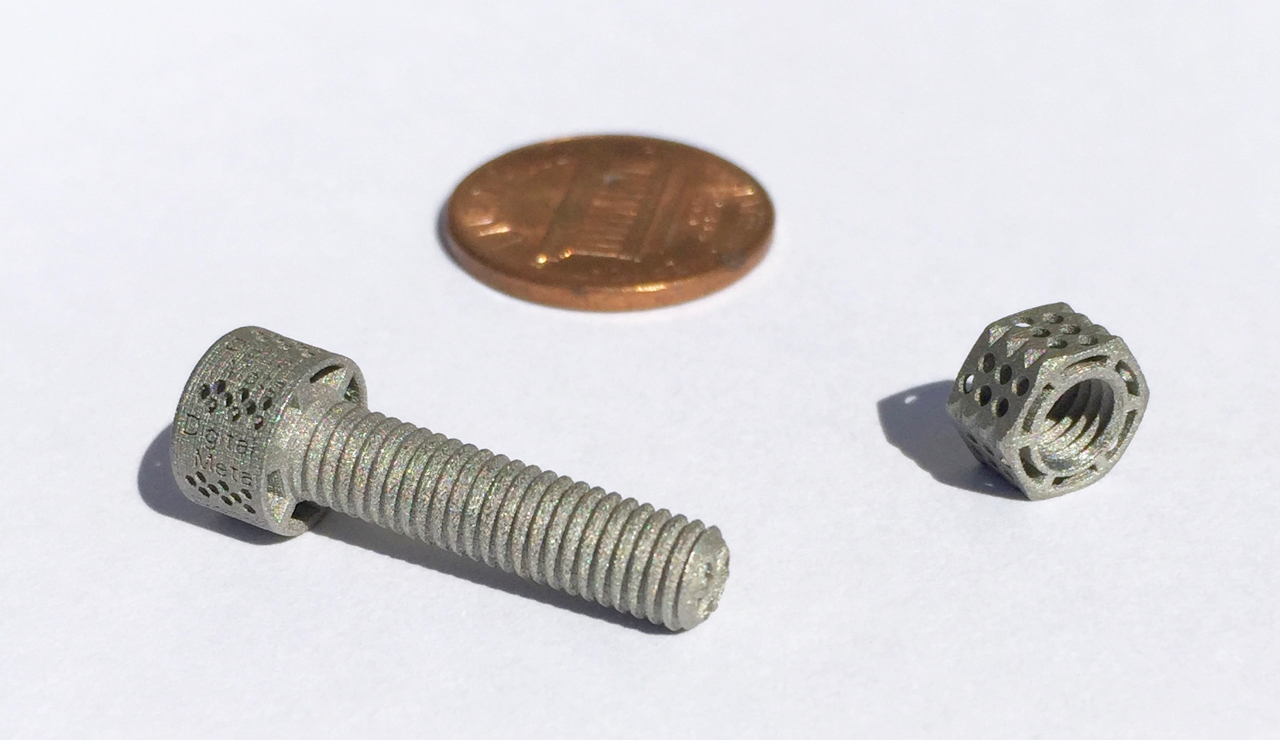

Another interesting use case is suggested here with this 3D printed nut and bolt. You’ll note that both have been hollowed out in a way that could only be achieved with this style of accurate metal 3D printing. Consider the possibilities if small metal objects could be weight-optimized in this way. In the aerospace and construction industries, weight optimization is a way to gain leadership in the field; the concept shown here could suggest a similar effect could be achieved on the small scale, too.

However, I think the problem is pricing. Höganäs has designed their current product line with small build volumes that limit the capabilities of the device to the production of small parts or fashion items. I believe there could be much larger uses for this amazingly simple metal 3D printing technology.

Via Höganäs