Researchers at Harvard have developed a truly fascinating 3D printing technique that shows the limitations of current technologies.

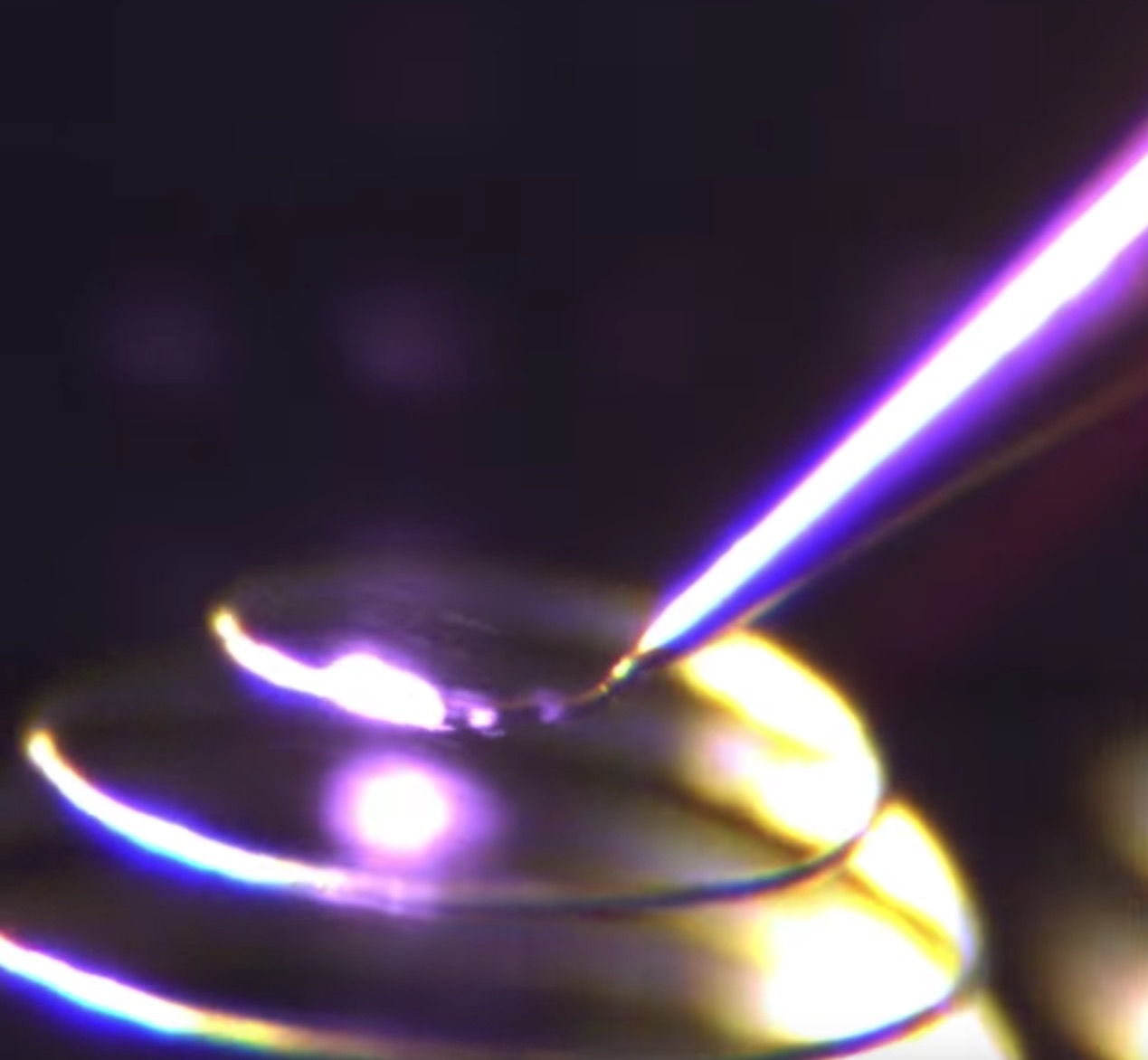

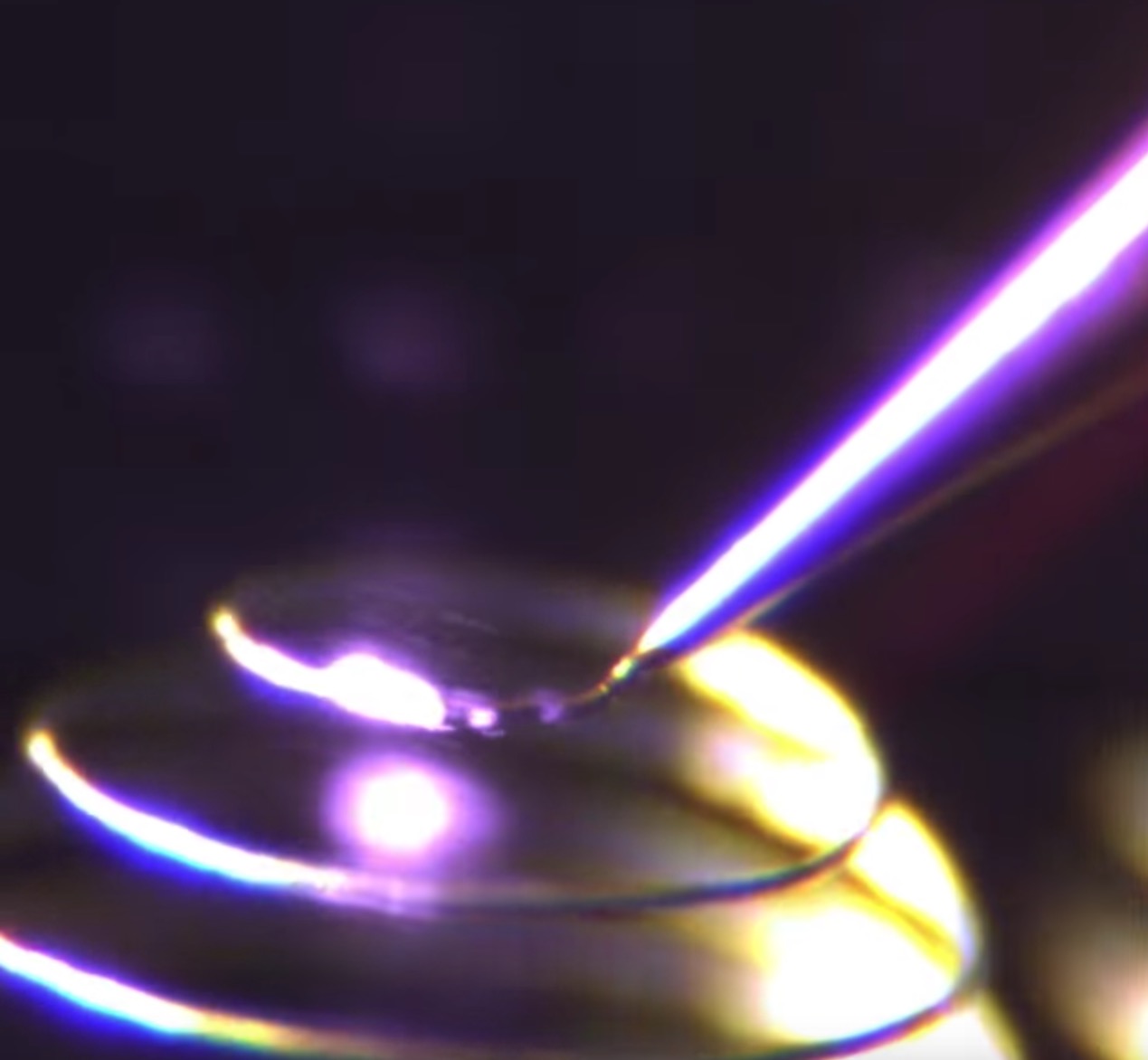

They call it, “printing metal in midair”, and that’s pretty much exactly what happens. Basically they have developed a way to flow a liquid “ink” containing silver nanoparticles to a nozzle, whereupon they are blasted mercilessly with a high power laser. The energy instantly melts the silver, which almost as instantly solidifies into a structure. By moving the nozzle quickly through space, the print seems to require no support material.

This is because a) the metal solidifies before drooping can occur, and b) it’s metal. Metal is strong!

Here’s a quick video to show how this actually works. Watch carefully and you’ll see the nozzle lift off the surface and print in mid-air:

For me, this highlights a major limitation in current 3D printing approaches: rasterization. Essentially, all 3D print technologies today use a “rasterization” technique in which the object is divided up into layers which are successively built.

While this approach is more-or-less efficient when printing certain geometries, like a vase or solid object, it is not at all efficient when printing a more complex object that has many separated structures. The rasterization technique requires vast movements to and from elements distantly located on the print plate. If only those tentacles could be printed vertically, we’d avoid a ton of extruder movement!

But now, that’s actually true. The Harvard technique DOES permit individual elements to be printed in isolation and without regard for layers.

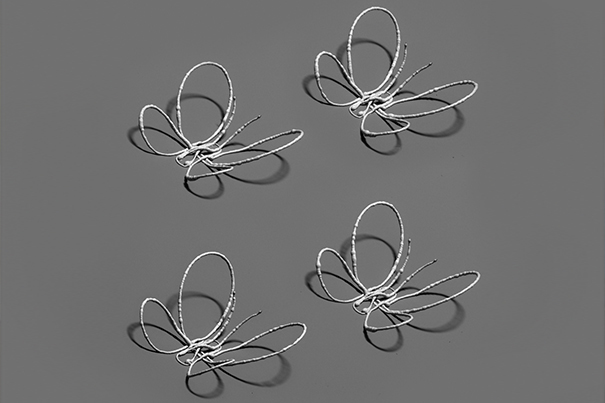

Here we see some sample prints using the new technology. Imagine how efficient it could be to print them by merely following the curve of the wings.

Those familiar with laser cutting will definitely appreciate this new approach; in laser cutting, “raster” operations are very slow compared to “vector” cutting. The same should be true with this new 3D printing approach.

To be very clear, the software required to develop a 3D (instead of 2D) tool path for arbitrary geometries is not going to be straightforward, but if made, it could revolutionize how prints are done. There could be very significant speed advantages of doing so.

Via Harvard (Hat tip to Tom)