Charles R. Goulding and Preeti Sulibhavi explore how grassroots initiatives in Ukraine are leveraging 3D printing to rapidly scale drone production.

The Russo-Ukraine war is in many respects a drone war. We recently authored an article on Russian grassroots efforts by numerous small businesses including a leading bakery to build drones all using 3D printing. Some Russian shopping centers have been converted into drone factories.

In Ukraine there is a grassroots initiative to build First Person View (FPV) drones with explosives to strike Russian armored vehicles, trucks and soldiers. The FPVs have become more essential due to ammunition shortages. As Ukraine struggles to defend itself against Russia’s invasion, the country is turning to an unlikely homemade solution – inexpensive drones built using 3D printers and commercial off-the-shelf parts. Unable to produce heavy weapons on its own, Ukraine has set the ambitious goal of building one million small explosive drones in 2024.

Leading the effort are scrappy startups like Sparrow Avia, which has quickly grown from start-up to 70 employees across three facilities producing around 3,000 drones per month. Only founded in 2022 with a US$500,000 investment, Sparrow’s growth has been fueled by high demand from both government and volunteer purchasers. Its 7-inch drone model with a 3-pound payload is especially popular for its affordability and maneuverability on the frontlines.

Behind Sparrow’s rapid scaling is the use of 3D printing, an essential tool to prototype and manufacture custom plastic components. The company’s facility houses rows of 3D printers humming away to produce the clips, braces, and chassis parts that make up its drones. 3D printing has allowed Sparrow’s engineers to rapidly iterate drone frames to optimize weight and durability. Components are tested on-site with flight trials to validate designs.

Meanwhile, off-the-shelf parts like motors and batteries are sourced globally, with the government eliminating import duties to encourage local manufacturing. But even the purchase of COTS components has been a challenge considering supply chain strains. Sparrow spends around US$14,000 per month on imported parts, with delivery delays being an unfortunate norm.

Beyond Sparrow, Ukraine’s drone ecosystem encompasses over 60 models from various makers. From cargo drones to kamikaze attackers, the government has offered tax breaks and large purchase contracts to grow this homegrown industry. It has set up dozens of decentralized workshops to mitigate risks from Russian targeting.

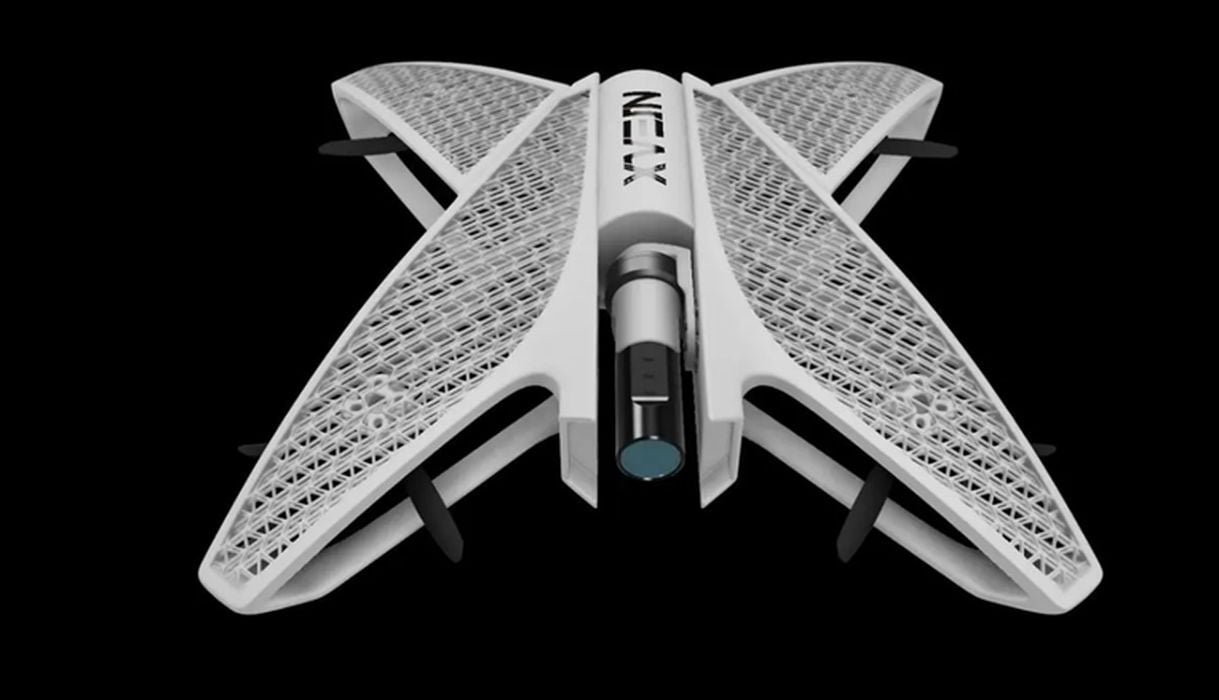

Early players in defense drones, like Athlon Avia, have expanded from quadcopters to fixed-wing unmanned aerial vehicles with 30-50 km ranges. Its US$20,000 X-01 model is hand launched and carries a 10 kg warhead to loiter over targets before crashing into them directly. Athlon Avia has also grown to 120 employees across Ukraine after being founded in 2021.

Ukraine’s drones may lack the sophistication of American-made models, but they provide critical asymmetric warfare capabilities given the country’s scale of need. Russia’s advantage in numbers means sacrificial drones are necessary to hobble armored vehicles before engagement with Ukrainian forces. Kamikaze drones also help conserve Ukraine’s dwindling stock of anti-tank missiles.

The government aims to eventually produce drones capable of autonomous strikes, eliminating the need for a manual pilot. But Russia is also investing heavily in electronic warfare equipment that can jam the communication links critical for drone control. Surviving in an increasingly contested airspace will require Ukraine’s startups to continue innovating.

The Research & Development Tax Credit

The now permanent Research and Development (R&D) Tax Credit is available for companies developing new or improved products, processes and/or software.

3D printing can help boost a company’s R&D Tax Credits. Wages for technical employees creating, testing and revising 3D printed prototypes can be included as a percentage of eligible time spent for the R&D Tax Credit. Similarly, when used as a method of improving a process, time spent integrating 3D printing hardware and software counts as an eligible activity. Lastly, when used for modeling and preproduction, the costs of filaments consumed during the development process may also be recovered.

Whether it is used for creating and testing prototypes or for final production, 3D printing is a great indicator that R&D Credit eligible activities are taking place. Companies implementing this technology at any point should consider taking advantage of R&D Tax Credits.

Conclusion

With the fledgling drone industry now collectively producing thousands of units per month, Ukraine is banking on strength in numbers. Affordable 3D printed components coupled with commercial electronics have enabled rapid scaling to backfill depleted weapons stockpiles. If drone startups can maintain output momentum, their suicide striker forces stand to play an outsized role in defending the embattled nation.

By the time the war ends, Ukraine will have a more sophisticated drone industry including artificial intelligence integration. Hopefully, this new wartime expertise can then be put to beneficial peacetime use.